The last time I spoke with Anthony Sorice we talked about change. He mentioned that while working at Threes — his first job in the industry — and then at LIC Beer Project, he had seen IPAs replace his preferred farmhouse and Belgian styles. But while he toiled in the hoppy beer programs of Threes and LIC, he was working on his own project with friend and business partner, Ryan Mauban. Sorice is now returning to his roots (sorry, it’s too easy) on Long Island, giving a much-needed boost to the nascent LI craft beer scene and focusing on brewing with mixed-fermentation and fruit, rather than hops.

History is an important part of Root + Branch. The name of the brewery is lifted from Sorice’s past, a reference to his former philosophy professor’s Libertarian Socialist zine. The beers he’s launching with are collabs with his four oldest friends in the New York beer scene. (And one of these beers is a nearly extinct beer style.) It’s a move away from played out hype, and toward genuinely pushing beer forward in ways that aren’t double dry hopped.

A notable exception from the collaborations is LIC Beer Project, his most recent home. His relationship with LIC turned lukewarm as Root + Branch became more real. It was a sobering lesson about the business of craft beer. In an industry that continues to grow competitive, it doesn’t make a lot of sense for an employer to let his Head Brewer have a competing side gig.

But Sorice needed a creative outlet. Root + Branch offers him the chance to brew the style of beer he’s excited about and to experiment with fruit, with ancient beer styles, and with friends in the industry.

JP: You guys are launching mostly with collaborations. Only one beer isn’t a collab.

AS: Yes, so we’re gypsy brewing right now. 12 Percent Beer Project reached out to us and they’re supplementing production for some of their existing brands like Evil Twin, Stillwater, Omnipollo. They brought on Decadent, us, and Fat Orange Cat. And they’re supplementing all their gypsy brands out of this space, Thimble Island Brewing Co. in Connecticut. It’s a massive 30,000 square foot facility. They have their own brand, but the space is just way too big. They have a close relationship with the guys at Torst and Ryan and I had been working at Torst for like four years and Bartley, the GM/owner, knew that we were working on this project. I think he passed the word along to Alex at 12 Percent because we got an email randomly that was like, “Hey, checked out your project. Think you guys are doing some really cool stuff would you want to work with us?”

JP: Launching with collabs really speaks to the importance of brewery friendships in the industry.

AS: Yea, it was important to me. The four collabs I did were with four of my closest friends within the New York beer scene. And even going forward I’m not just going to do fucking collaborations for the sake of marketing. It’s so played out. So I want it to be thoughtful and something I could do with my friends and a fun project to work on. Like when I was at LIC I brewed a handful of collaborations with these dudes who’d show up, stand around, and be super fucking awkward and we’d have nothing to talk about. It just never seemed natural or organic. If it’s not meaningful, I don’t want to do it.

JP: How do you think people respond to collaborations? You’re being really intentional with them, do you think that will come across?

AS: I hope so. I try to put that message forward. Whenever I do a collaboration I try to take a photo, put it up on social media, and give some meaningful information as to why we’re here and why we’re brewing this style of beer.

JP: In terms of the styles of beers you’re launching with, you’ve got a pale ale, two DIPAs, and then a Lichtenhainer? I don’t even know what that is.

AS: A Lichtenhainer is a nearly extinct style of beer. It’s where gose was four years ago before the style just popped. Berliner Weisse happened and everyone started brewing gose for some reason. It’s an old-world German style, the process is very similar to a Berliner Weisse. It’s low ABV and incorporates smoked malt. So it’s a smokey, tart, little table beer.

JP: Was there a personal reason for why you wanted to launch with that style?

AS: My first brewing job was at Threes. When Greg, the former head brewer, was brewing there he wanted to focus on farmhouse ales. We started out with a table beer, a couple saisons, a pilsner, a baltic porter, and one IPA. And it was always going to be that one IPA. And then slowly we got to brewing a pale ale, a double IPA, and focus shifted away from the farmhouse ales and stuff that we wanted to brew to stuff that we had to brew. And we had to brew that shit to keep the lights on. So when I was talking to Matt and Joel about the collab we realized we shouldn’t do an IPA. It’d be a disservice to Greg. We went outside the box.

JP: Between the can designs and the logo, the art for Root + Branch has been awesome. Who does the artwork?

AS: I come up with the concept for them and then my girlfriend makes it. She’s a graphic designer and she does all the illustrations. So I’ll be thinking of this and she’ll draw four prototypes and then we’ll dial it in and narrow it down to one.

JP: It feels familiar in some ways to this region. Some of it has the feel of Hudson Valley’s artwork. And Kenny pointed out that the logo looked similar to Equilibrium’s.

AS: Early on we were afraid because when we were doing the prototypes the logo didn’t connect all the way and it was almost identical to the Equilibrium one and I was like, ‘We can’t use this it’s way too close.’

JP: Did you see the movie Arrival? It kind of reminds me of the alien language.

AS: Oh yea!

JP: How long have you been working on Root + Branch?

AS: I was at LIC for about two and a half years and the idea started when I was at Threes. So it’s about three, three and a half years old. But it didn’t really come to fruition and I didn’t start giving people samples of my beer until I had just started at LIC. I figured out the name and that I wanted to do a brewing project and then was slowing learning the ins-and-outs of professional brewing.

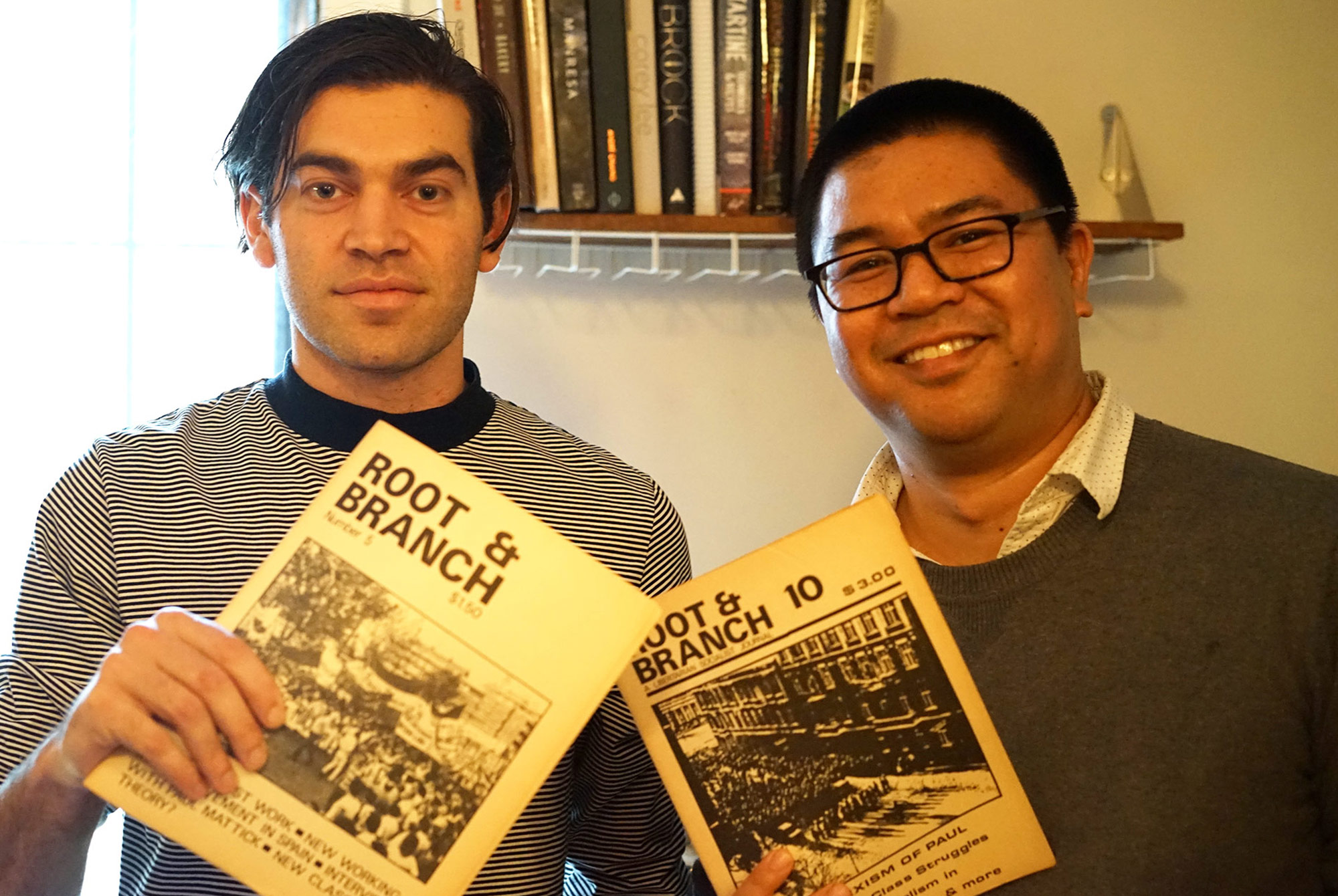

JP: Where did the name come from?

AS: So the name actually comes from this [Reaches into bag and pulls out a manilla envelope]. They are pamphlets from a literary group that my old philosophy professor had started with his father when he was a graduate student at Harvard. So it was like a Libertarian Socialist journal. I was studying at Adelphi on Long Island and I sort of became attached to this professor. He ended up mentoring me all the way through undergrad, through graduate school. I was at grad school at Brooklyn College and on my days off I would drive out to Long Island and attend all of his courses.

And at the time, when I was in grad school, the Occupy Wall Street movement was going on and he was a big speaker at that; he was doing tons of forums and panel discussions I finished my Master’s Degree the same week I got offered a job at Three’s and I just ran for the job opportunity. In the back of my mind, I was always into beer, always kicking around the idea of starting a project with some homebrew friends. So the name came from that and when I told him I was naming it after the pamphlets, he had no idea I even knew about this. He has a Wikipedia page with a short entry about it and I thought it was a great name. And I told him about it and one day I got a package in the mail and he had sent me his last personal copies of the pamphlet after he retired. So eventually we’ll frame these and hang them up in the brewery.

JP: Aside from just sounding good, is there any deeper meaning behind it?

AS: So the name really references the movement of grassroots reform and “root and branch” is more of a complete overhaul of an entity. The project is going to be based out on Long Island–I always intended it to be built out there–and there wasn’t really anything going on there. There was the Southampton Publick House but they stopped doing specialty releases and no one was really focusing on quality beer. And the beer scene was kind of bleak out there so we’re trying to bring a new, fresh overhaul to craft beer on Long Island. And now Sand City is out there fucking killing it and they’ve paved the way and there’s room for awesome beer out there. The market is wide open out there. Long Island deserves good beer. There’s so much of it in the city, it’s saturated with it.

JP: How do you see yourself fitting into the Long Island market?

AS: Sand City is basically 100% focused on producing hoppy beer and they’re doing it well. For us, I brew hoppy beer and I think I brew it relatively well, but my personal interest is in mixed-fermentation, mixed-culture saison, and Berliner Weisse. I love incorporating fruit into my beer. And something that people aren’t doing is using the agriculture. So on the eastern end of the island there are tons of fruit farms that grow apples and peaches and berries. I know one producer that grows really awesome cherries. So I want to do really small batches of mixed fermentation saison and Berliner Weisse and then go out there and get as much fresh fruit as possible. I want to try to introduce terroir into the beer.

JP: Terroir is becoming a part of the industry language more.

AS: A lot of breweries opening up now are doing spontaneous fermentation which is rad. No brewery is going to get the same profile doing spontaneous fermentation. It varies from place to place depending on what’s surrounding it. So it’s great to see people incorporating unique terroir into their beer.

JP: So, when did you officially leave LIC?

AS: December.

JP: How was your relationship with LIC after you left?

AS: So, I didn’t necessarily want to leave LIC. For the last 6 to 8 months I was in this weird position. I had been promoted to Lead Brewer pretty early on and for the last 6, 7 months I was being introduced to people as the Head Brewer but I was never officially promoted. I received a text message from my good friend Dan, who is a specialty brewer for Mikkeller San Diego, and he sent me a link to a ProBrewer forum post where a lot of people in the industry put up job listings. And there was a listing up there for my job so I brought it up to Dan and said, “Hey there’s this Head Brewer job but you’ve been telling people I’m the Head Brewer.” And so he said, “Yea, I know you have this brewery project and just wanted to keep my ass covered.” And I told him, “You know I have no intention of leaving anytime soon.”

It was all good but a couple weeks go by and I get called up to the office with Dan and–I don’t know if it was like a lawyer/accountant– but they sat me down and had this intense discussion. They asked me, “So what are your plans going forward? We know you want to start gypsy brewing, so what does that do for us? How does you working here and then putting beer out under another name benefit LIC? Now you’re going to be my competition.” And I said, “I guess it doesn’t benefit LIC.” And they gave me this new employee contract with a non-compete agreement and I couldn’t sign it. I had been working on this for two years. I was at the point at LIC where I wasn’t learning anything anymore and it didn’t really make sense for me to throw away my future plans while I’m stuck in a job where I’m doing the same shit over and over again. I felt like I didn’t have full creative control, which was not super exciting. So I went in the next day and said, “Hey dude I’m not signing the contract so here’s my notice.” I got a call later that evening saying, “Yea, don’t come back.”

JP: Wow. That’s rough.

AS: I wanted to do everything with all my close people in NYC for the collabs and I reached out to Dan and he said, “Yea that sounds cool.” And then he just ghosted me.

JP: That’s shitty. I remember you saying that you had felt like you were doing the same thing over and over again at LIC the last time we talked. What do you think you’re bringing with you from your time at LIC and what are you hoping to leave there?

AS: I definitely want to leave behind the hoppy beer program over there. Before I started there they weren’t brewing hoppy beers. They were focused specifically on Belgian styles of beer. At the time we only had three fermentation vessels. One was dedicated to mixed fermentation with brett and sacc for farmhouse ales, the second was for Belgian strains, and then they had a rotating tank where they would switch yeast in and out of it. I helped implement the brewing process of the hoppy beer so we still use all of that technique today.

What I’m taking away is some experience working with wood. Transferring beer in and out of barrels, blending beer, so that was a great learning experience. And then also all the mechanical stuff. Dan has a construction background, prior to opening LIC he was building breweries. So he has a fucking immense amount of experience dealing with pumps and the physical mechanics of making a brewery run. Dude, I was in school studying history so working with tools was a whole new world for me. That’s invaluable: fixing pumps, rerouting piping, figuring out a way to manipulate the system to get it to do what we want it to do. I definitely learned a lot in that aspect.

JP: Obviously Root + Branch is no longer a “side project,” it’s your full-time gig. But it started as a side project brewery. And you’re seeing more of those in the industry now. Where do you see that going?

AS: There’s a lot of ego in the industry. So it’s hard to allow an employee to start producing his own stuff out of the brewery because it kind of clashes with your brand, but then there are just genuinely open people that want to support their employees. I guess I don’t really know many side projects aside from Side Project. I think it’s great. Cory had brilliant ideas that weren’t being implemented at Perennial and they started brewing his beer out of Perennial and it drove all this traffic there. It benefits the brewer, who wants to branch out and do his own thing, and then it brings all this attention to the host brewery. I view it as a win-win for everybody. It’s a great way to allow your staff to practice artistic expression.