Despite being named as one of RateBeer’s Best New Brewers of 2018, The Referend Bier Blendery, which produces incredible spontaneously fermented beer, has flown under the radar. People aren’t exactly clamoring for blended beer the way they are the hottest IPA. Located in Pennington, New Jersey, Referend’s closest neighbor of note is Troon Brewing, which has made a name for itself by pumping out highly sought-after juicy beer. For Referend founder James Priest, though, spontaneous fermentation isn’t business. It’s a religion.

Walking into Referend, I expected to be greeted by a wizened master-blender, who reflected the stuffy, wait-a-while-before-you-drink-it, attitude of spontaneous fermentation. But, Priest didn’t strike me as someone who had devoted himself to the ancient art of lambics. There were no hooded robes or hushed secrets. Sitting down across from him, Priest reminded me of comedian Mike Birbiglia, who raises his voice musically as he begins a joke, pauses to draw the audience in, and hits with his punchline. In Priest’s case, the punchline was a delicious bottle of spontaneously-fermented beer, and I was hooked.

Before opening Referend in 2016, Priest had worked at wineries and bigger breweries, taking lessons from both to operate a Lambic-style blendery. Priest, who has an auspicious surname, treats the blending process with the same reverence as a religion. Priest’s taproom, which is sparsely decorated, features a repurposed hymnal board and small statuettes holding candles above the barrels. At one point during our conversation about spontaneous fermentation, he says that he “believes in it,” the same way someone would say they believe in a higher power.

The taproom doesn’t necessarily look like a church. On the hymnal board there are beer names, not psalm numbers. The organ has been replaced by a turntable spinning Feist records. There’s no Body and Blood of Christ. There’s just a shit ton of spontaneously-fermented beer. Welcome to the church of Referend Bier Blendery.

John A. Paradiso: Can you talk about the process of blending?

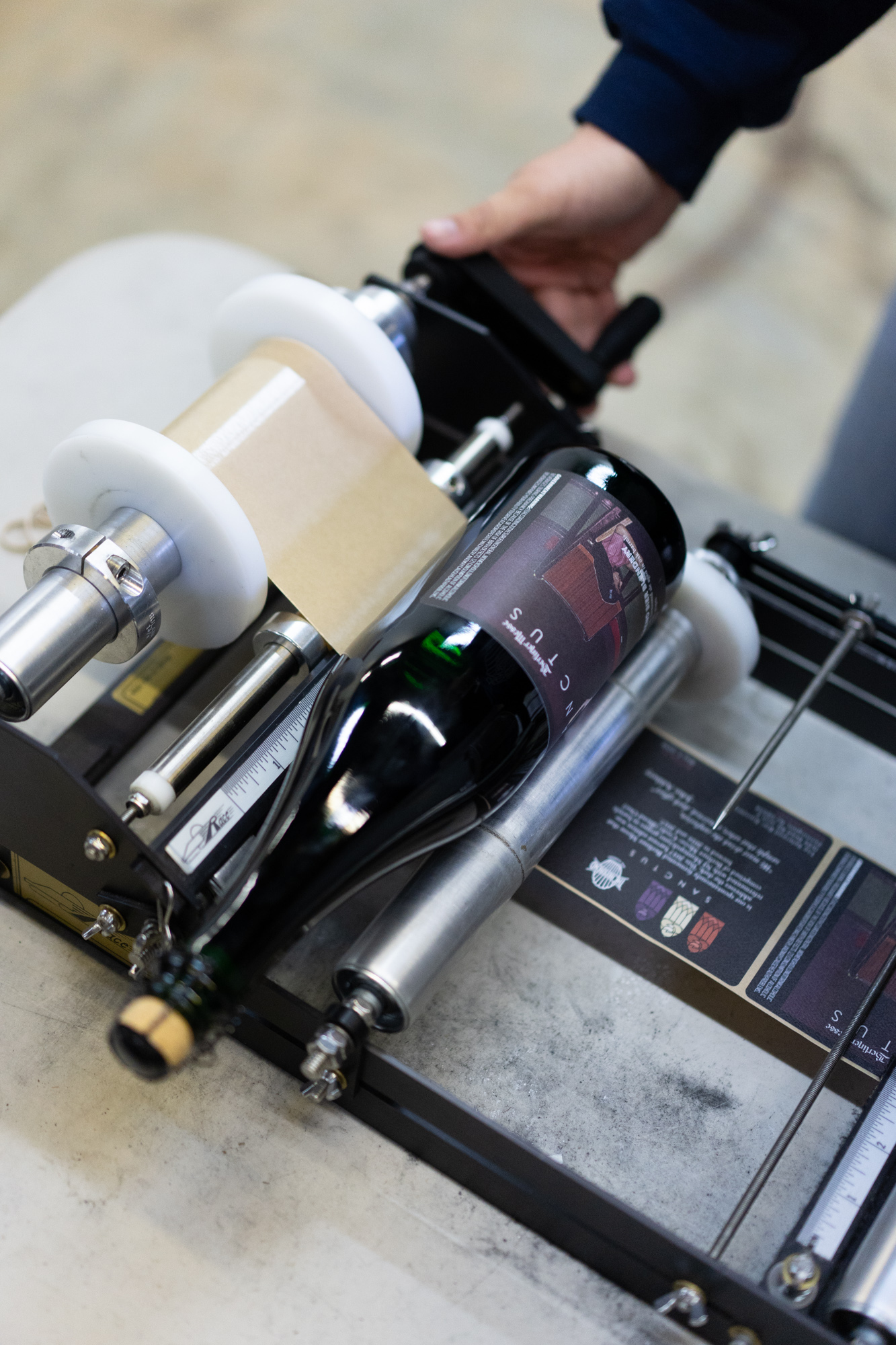

James Priest: The “blendery model” is the most succinct way to say that we don’t have a brewhouse. We don’t physically do the brewing here. We go to other breweries to do all of our brewing, we brew our specific batch of wort, pump it into our mobile coolship, let it cool, bring it back, and pump it into barrels.

The blending is mostly post-fermentation. We’ll blend sometimes with different ages for each of the beers, because each age contributes something different. Blending is about looking for complementarity, knowing that a beer is better off for the blending. At times, barrels are so good that you don’t want to do anything to them, so we’ll package those un-blended. But those are pretty rare.

JAP: This isn’t a typical brewery. Is there a lot of explaining involved when folks come in here?

JP: I feel like education is important for any brewery. It’s sort of doubly hard for us because in order to explain what we do, we have to explain everyone else’s process. “The beer you usually enjoy, here’s how that’s made…And here’s how we do it.”

I do obsess over the process. So then it’s about communicating the process adequately and transparently. Because spontaneous fermentation especially–I think–requires transparency on our end and trust on the other end. They’re both constantly hand in hand because there’s nothing that would prevent someone from adding yeast to something and claiming it’s spontaneous. All we can do is be open and transparent about it all. Otherwise, the magic of spontaneous fermentation doesn’t exist. I really believe in it.

JAP: What do you mean by that?

JP: I believe that it works. Lambics used to be reserved for a special place in Belgium and until Allagash starting making spontaneously-fermented beer in the US, no one thought you could do it. But yeasts are native to just about everywhere. So spontaneous fermentation can be done anywhere and is already being done without humans.

I believe that there’s just some fairly easy and straightforward essential yeasts and microbial life present everywhere. And that is sufficient to make good beer.

And it’s my personal belief that that is the most natural way to make beer.

JAP: What are some of the benefits or challenges from being where you are in rural New Jersey?

JP: We have a lot of fruit available that we wouldn’t have elsewhere. Then again, the whole of the West Coast, I am in jealous awe of. There’s just so much more agriculture out there. Such that when you go to a grocery store in New Jersey, 98% of it is coming from South America, Mexico, the West Coast. I think we’re probably buying a disturbing proportion of some of the fruit grown in New Jersey. We’re down in South Jersey like twice a week, grabbing what we can from the farms, and then tossing them into beer.

One of the simultaneous challenges and benefits is that New Jersey is a comparatively young beer drinking area. But even having new breweries open up and letting people even see a baseline of craft beer is really great. It’s what was happening like 10 years ago in Colorado or Vermont. And it’s weird for us. Because of course a frame of reference helps. But, we do get a lot of people who don’t know beer, don’t like beer, and maybe they’re wine drinkers, but they end up loving what we make. It tends to work for people who have a narrow definition of what beer is and they’ve got an open enough mind to try something that is called a beer, but reminds them of wine. Introducing this to people who are new to the style who end up at least intrigued by it, I’ll take that. That’s how it was for my first experience–just raw intrigue for what was happening in my mouth.

“I don’t know if I’d call it art. But it sure as shit isn’t science.”

JAP: Can you remember that first time?

JP: I think it was at Novare Res in Portland, Maine and Cantillon Gueuze was on draft, which was a thing I guess back then.

JAP: Back when you could find it around.

JP: I mean it went quickly and it was expensive but there were like five taps with Cantillon. I wouldn’t even say I enjoyed it that first time. But I returned to that glass more than anything else.

JAP: How would you feel about people approaching your beer like that?

JP: I think that’d be great. I enjoy being a little out of my depths. I like being puzzled and confused, I like surrealist shit. Anything that has that riddling quality, where it’s not immediately apparent, and that’s what appeals to me most about this style of beer.

JAP: Do you approach wine drinkers and beer drinkers the same way? Do you have a roundabout way of getting to the same answer when those two types of drinkers ask about your product?

JP: Each will definitely be recommended different beers. I think there’s something for both. Ideally, they come to accept it for what it is and not sort of the framework they have of beer or wine.

JAP: Did your background in the wine industry shape how Referend came about?

JP: Yes. It was more my specific background, which was more pragmatic and learning the tools of the cellar and barrel care and maintenance. How to work with wood well. Even the sanitation procedures–in a winery they are much more lax than in a production brewery (Laughs). And should be, I mean it makes sense. Star Sans and hot water is as serious as we get.

But I think it gave me an appreciation for wine as an agricultural product. I talk about natural wine probably more than is good, considering everyone’s talking about it, (Laughs) which is great–I think.

JAP: Potentially. It depends on specifics–

JP: Yes exactly! It does. I think there is as strong an affinity with natural wine and doing these production methods as there is even with Lambic. We have more in common with natural wine makers than we do with…sour brewers, who are pitching cultures. And that’s not a knock on them, it’s just different. Different philosophically I think. Maybe methodologically, if that’s a word. (Editor’s note: it is.) We’re just trying to guide it using no chemicals and even minimal temperature control. We like to see some fluctuation in temperatures in the barrel room. But a cave would be nice. We’ll go underground instead of using all the vertical space.

JAP: When humans eventually go underground, you’ll have a field day.

JP: Right. If nuclear holocaust happens, we’ll be going under. And that’ll be great for long aging stuff. Cheese, beer, wine.

JAP: I have seen a lot of breweries taking notes from wine and leaning more in that direction with their beers. Do you see that happening?

JP: I think how it’s being portrayed is a more facile assessment where it’s like, “These breweries are using grapes.” Learning from the wine industry rather than just trying to…I don’t know, add grapes to beer is hugely useful.

There are just so many different natural wine makers around the world using their own ingredients and who have their own philosophies and practices. It just shows you that there are so many ways to make a wine and, when we start to do similar things, so many ways to make a beer. The initial scope of this was Lambic-style blendery model and that’s limiting.

JAP: Some breweries can benefit–and do benefit–from speed and pushing things out. But, for you, it’s a matter of patience and of waiting for things to run their course.

JP: It takes a specific temperament to do this. I don’t know if it’s a good temperament; I don’t want that to sound like I’m bragging. But you have to let nature do its thing. Even if that means it’s going to ruin it.

It’s sort of like–I don’t have kids so it’s a fucked up analogy–but if you’ve got a kid and they’re not wayward to the point of self-destruction, you’ve got to let them burn themselves on the stove. Right? We’ll dump a barrel to let the other ones achieve what they were meant to in a natural way. It sounds like I’m advocating for child mortality rates or something.

JAP: That’s a wrap. We got our headline: “Referend Wants More Dead Children.”

JP: Damn. (Laughs)

But, patience happens at a lot of different stages of this. There’s time in the barrel and there’s also time in the bottle. And it definitely helps to have more beer. When we had like three bottles bottled, that’s a brutal time. Now we’ve got 15 or 18 waiting to be released and that’s much more manageable. Where you’re not just like, “Come on! Hurry up and taste good!” We can say, “Ok. Well that one does now taste good.” The pressure is a little lower.

It’s extremely important for quality and self-preservation to wait for it to get to a point where you’re happy. And that’s the hardest judgment call to make. We have beers that are clean and decent, but we don’t yet love it and we know we will love it. Almost everything improves with time. Although I try not to fetishize the extreme aging of things.

JAP: With the assumption that beer is a balance of art and science, where do you fall?

JP: Spontaneous fermentation more than anything else ruins any attempt at science. Because the very act of opening it up to the entirety of the air means you’re ceding all control. So I would say heavily on the art side of that in those terms. I don’t know if it is that as a spectrum. Like, I don’t know if I’d call it art. But it sure as shit isn’t science.

Liked this article? Sign up for our newsletter to get the best craft beer writing on the web delivered straight to your inbox.