Shop

Balance Brewing: How Manchester’s Only Wild Ale Brewery Pursues One Moment of Equilibrium

⚖️

Here Are Hop Culture's Top Stories:

On a blustery Monday evening, I snaked down a side alley next to the Manchester Piccadilly station. Under one of the many bricked archways, I pressed my nose against a set of glass windows. Inside, a man on a forklift looked set to rev the engine and drive right through me.

Instead, he hopped off and came over to say hello, mentioning he just needed to move a few more barrels before we could sit down and chat.

Looking around at the stacked-sky-high casks, I couldn’t find anyone else helping him.

Just James Horrocks, co-founder of Balance Brewing & Blending in Manchester. As Horrocks popped a bottle and poured me a small glass of his table beer, he explained that Balance Brewing, perhaps quite fittingly, is currently just a two-person operation. Horrocks and his partner Will Harris hold down the fort at one of Manchester’s most intriguing new breweries.

Between the two of them, they run one of the U.K.’s best forage and wild ale breweries under one of the city’s main railway lines.

“This is a tiny mixed-ferm project and very exciting,” Pellicle Founder and Author of Manchester’s Best Beer Pubs and Bars Matthew Curtis wrote me in an email. “I urge you not to miss it!”

I’m so happy that I didn’t.

Falling in Love With Lambic. It’s Not for Everyone

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

“There are loads of places you could start the story,” Horrocks told me, pausing for a minute as he uncorked one of Balance Brewing’s exquisite ales and poured us a couple of glasses.

We sat at one of the taproom’s tiny tables. Legs crossed, Horrocks perched back on the black chairs, savoring a tiny moment of respite.

Throughout our hours-long conversation, Horrocks often took time to respond, giving me the classic impression of a duck treading water—calm on the surface, paddling madly underneath.

I felt perfectly content to give him time to consider while I sipped on the one-hundred percent attenuated, low-ABV, saison-esque table beer brewed with oats, rye, and a house culture.

Eventually, Horrocks continued: “I remember getting into craft beer about a decade ago, starting with IPAs as ninety percent of people do, but I started hearing about these, like, world-famous beers, particularly Belgian beers like Cantillon.”

When one of his best friends visited, Horrocks noticed a local bar pouring the Belgian lambic.

“We tried Cantillon Kriek for the first time and just absolutely loved it,” Horrocks recalled. “That was the very first moment of, like, wow, what is this?”

Unlike anything Horrocks had ever tasted, the spontaneously fermented beer aged on cherries blew his mind. Lambic, in general, grabbed him theoretically by the shirt collar and wouldn’t let go.

“There’s something magical about how every bottle, every barrel, every moment that you drink it, even, like, the same batch, you drink it two minutes later, and it’s changed,” Horrocks explained gleefully.

In his black Squawk t-shirt (a former brewery he worked for that recently closed) and scuffed mustard yellow brewer boots, Horrocks could be mistaken for just another traditional brewer. But as soon as he starts to talk about lambic, you see the gears shift. Like pulling out a book on a shelf that opens a door to a secret room; something just clicked.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

His hands become animated like they were trying to solve a Rubik’s Cube, and his eyes lit up like magician’s flash paper.

Harris had a similar moment. One day after finishing classes, he stopped at his local in Sheffield for a beer. For some reason that day, he ordered a 375mL bottle of Drie Fonteinen Geuze.

“I was told I probably wouldn’t like it,” he shared with me. “But I absolutely loved it!”

Harris says, “the deep complexity, leathery funk, and masterful cohesion of flavours were extraordinary.”

Totally fascinated, Harris moved onto Krieks, other fruited Lambics, and American sours from The Rare Barrel, Jester King, de Garde, etc. “I loved tasting these amazing flavours,” he said. “Digging into where they came from biochemically, what Brett does differently, and what other pathways yeast uses to create such complexity.”

But to be far to Harris’ local, Lambic is a niche beer style. Not everyone has this same chemical reaction. A lot of people find spontaneously fermented beers too weird or out there.

Horrocks says even three years later, people still walk into the brewery asking for IPAs.

They don’t have any.

Everything is mixed-culture, fermented, and produced in barrels with wild yeast like Lactobacillus, Brettanomyces, and Saccharomyces.

“It’s a very difficult thing to describe,” Horrocks told me, noting the best thing to do is get a sample in their hands. “Funky is somehow the best descriptor, yet it doesn’t really mean anything.”

You’ll find this push and pull, this see-sawing, teetering back and forth throughout Balance Brewing’s history: sticking to singularly brewing a style that you won’t find very often throughout the U.K.

When I pointed this out to Harris, asking why he’d want to open Balance, he responded, “Precisely because there weren’t that many of this kind of brewery.”

From Cantillon Kriek and Drie Fonteinen Geuze to Balance Brewing Saison

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Harris and Horrocks met while working together at Chorlton Brewing Company, Harris’ first real job after getting an MSC in Brewing at Heriot-Watt University, where he’d written a lit review on Lambic.

For Horrocks, the job was only his second.

“We wanted to work at Chorlton Brewing because they were a sour-focused brewery,” he explained. Mostly kettle sours, but still the closest either could find to the spontaneously fermented beers they loved.

“We met and thankfully just really got on and really loved this kind of beer,” said Horrocks. “There was very much this balance.” (Hey, his words, not ours).

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Even after each went on to work at separate breweries, they stayed close.

Harris spent three years at Track while Horrocks went to Squawk (hence the t-shirt).

In June 2021, they finally went for it, brewing their first beer for Balance Brewing as more or less a side project.

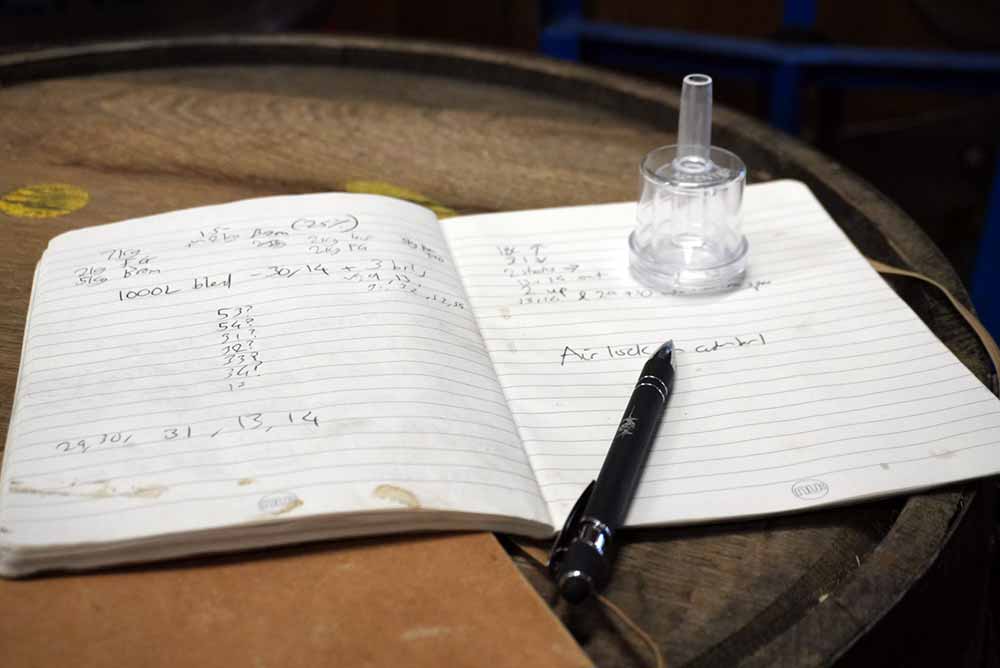

“We basically scraped a bit of money together from our respective families and had twenty-four barrels in the corner of another brewery,” Horrocks said.

They set up shop in a ten-square-meter area in the back of Manchester Brewing Company (which no longer exists). “We were just ridiculously small,” he said, noting they were still both brewing tens of thousands of liters of beer a week at their full-time jobs.

And while they would have loved to start with something like a Lambic, those beers require anywhere from one to three years minimum.

“We weren’t going to jump in and do spontaneous bear straight off the bat because it was just too risky,” says Horrocks. “With twenty-four barrels, if half of them went wrong, the business model would be ruined.”

Inspired by Crooked Stave’s Sts Bretta Saison, Horrocks thought, “If we can make something like that, we’re onto a winner.”

The Amazing Saison De Maison

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

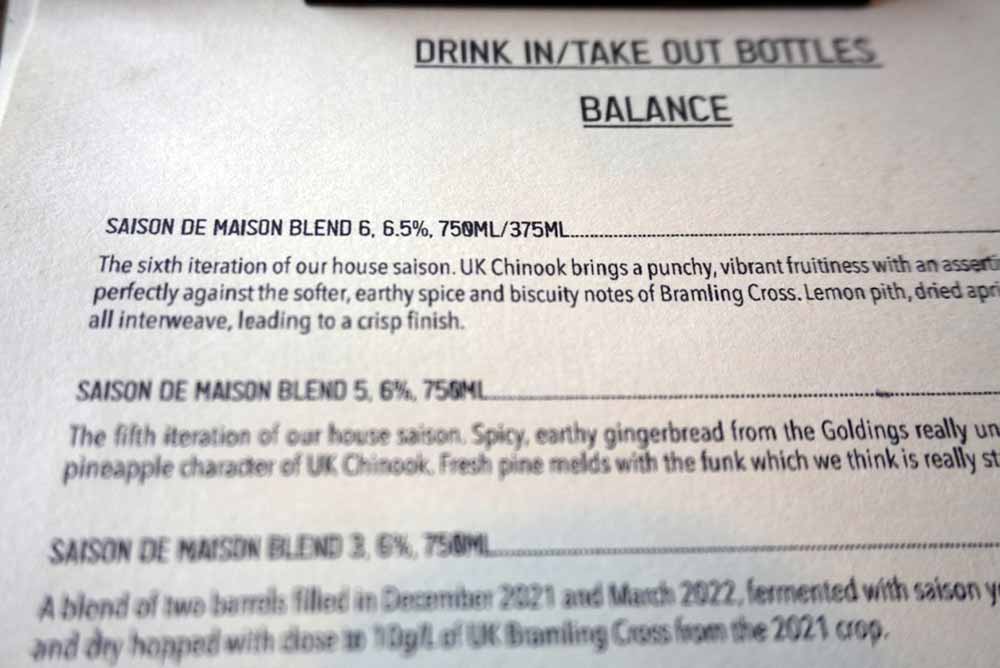

For their first-ever beer, Balance Brewing released Saison De Maison, a bretted saison that has become the brewery’s closest thing to a core beer. “It’s basically just a blend of a few different barrels of saison,” said Horrocks. “Generally, we’re going for a medium to low acid profile; dry hopped with various British hops for each blend.”

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Now on their sixth blend, Horrocks said they’re trying to dial in a final edition to serve as their house beer.

“It’s not precisely what we wanted because I think that’s impossible,” he told me. “But it was really, really close to what we imagined in those early days.”

The current version has a base malt of sixty percent Maris Otter and forty percent wheat, along with U.K. Chinook and Bramling Cross hops, which Horrocks says is a shoo-in for the final blend. “It’s got this curranty fruit character.”

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

But it’s another fruit that punches through—pineapple, a flavor Horrocks repeatedly told me he aimed for in this beer.

“I don’t know if it’s because we’ve been talking about it so much, but it feels like the most pineapple one I’ve ever smelled,” he said excitedly. “The pineapple is crazy in there; it’s absolutely the note we desperately wanted!”

The current hit me like an electric shock: pineapple, pineapple, pineapple. But nothing out of whack. The beer didn’t roast in the back of my throat with acidity or hollow out my cheeks with zippiness. Highly quaffable, this saison was probably one of the best I’ve tried in a long time.

For me, saisons are like a Backstreet Boys song you don’t hear often. But when it does come on, you belt out every single lyric at the top of your lungs.

You need that separation and that time to truly appreciate a classic.

After six iterations, Saison De Maison benefits from some seasoning.

“Time is an ingredient, and if you remove that, it would be a different beer,” Horrocks said proudly. “I’m really pleased with where the house culture has gone. … The barrels are getting seasoned. … Each time, it’s getting a little better.”

Foraging for a Future

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

If Saison De Maison represents Balance Brewing’s core, then its one-off wild stuff might actually be Balance Brewing’s future.

After hitting with their first saison, Horrocks recalled thinking, “We trust ourselves. We think we can make something really good, and there’s nothing in Manchester like this,” especially with roughly only ten to twenty other breweries focused on mixed-ferm in the U.K.

At Balance Brewing, which moved into its current archway location in December 2022, you’ll drink beers you won’t find anywhere else, especially if you visit multiple times. And we’re not talking about scarcity (although that does play a part, too); we’re talking about ingenuity.

“[We] create beers with distinctive character, using high-quality British ingredients that make people stop, think, and really taste what they’re drinking,” said Harris. “It’s a place to experiment with flavour and create thoughtful beers and blends.”

Many of the thirtyish beers Balance brewed over the last few years had ingredients I’d never even heard of, often foraged or sourced locally.

“I think it’s just such an amazing story to forage ingredients,” Horrocks shared. Hunting, picking, and brewing with your own ingredients adds a layer of unpredictability. Sometimes, the beer you set out to make takes a wild left turn.

And that’s when it gets really fun.

Balance Brewing’s Foraged Series

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

For Harris and Horrocks, creating beers is almost just as fun as drinking them. “I love the confidence and pride that ‘making’ brings to me,” shared Harris. “It’s a journey that won’t ever end. There’s always something to tweak, different ingredients to experiment with, and new challenges to overcome.”

For instance, in their first year, Horrocks and Harris made an incredible saison with mugwort and pineapple weed they found on what Horrocks calls a “foraging walk.” While they set out to find pineapple weed specifically, the mugwort was a bit of a “happy coincidence,” as Horrocks tells it. “There was just a lot around, and it has this coconutty dill-tasting notes. So coconut and pineapple seemed to make a lot of sense.”

The more we delved into foraging, Horrocks spoke more excitedly.

He told me that, in addition to finding their own ingredients, they have a “guy”—a foraging guy, more specifically, who owns a social media handle called Foraging That—who brings them different ingredients.

Horrocks stood up suddenly, scrambling back into the brewery and returning with an armful of tiny jars. Taking up half the table next to us, the gold-lidded clear crocks sported masking tape with names like Alexanders, Wild Carrot, and Fennel Pollen.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

“This is one of my absolute favorites,” Horrocks told me, handing me a jar labeled “Sweet Woodruff.”

I took a whiff of this sweet, warm, woodsy flower.

“It’s really different, kind of like perfume,” Horrocks said as he watched my nostrils flare. It’s really cool, isn’t it?” While Horrocks said they haven’t used it in a beer yet, he hopes to in the future.

By the time I put down the jar, Horrocks had moved on to the next. “Oh, that one’s good as well,” he said giddily, giving me one labeled “Fennel Pollen.” “It’s really interesting but a little bit harder to forage.”

I didn’t recognize many of the names on the jars nor the next ingredient Horrocks mentioned he’d already brewed with: Samphire.

“Sapphire?” I asked

No, Samphire.

“Saphir?” I asked again.

No, Samphire.

I realized that I didn’t actually know the word Horrocks kept repeatedly pronouncing.

“What is it?” I asked.

Horrocks described samphire as a sea vegetable that, for the last five or ten years, you’d only find on dishes in a fancy food place. “You would basically never see it in a supermarket,” he told me.

For this sour beer, Horrocks foraged samphire from an estuary in Wirral, about thirty to forty miles away.

“It’s a really interesting texture; it’s, like, crisp, I suppose,” noted Harrock. “But, like, incredibly salty.”

A few weekends after I left Balance Brewing, Horrocks told me they took the train to Edale, planning to forage for gorse for a new beer. He called the venture for the local plant unsuccessful, but “we did end up scoping out some pine needles and spruce,” he said. “We’ll be putting a couple of barrels onto them. … The spruce, in particular, is amazing, quite ‘hoppy’ tasting!”

Sourcing Locally for Apricots, Mushrooms, and More

What Horrocks can’t forage, he’ll find as locally as possible. Like using British apricots in one of the best beers he feels he’s ever made, an apricot wild ale called Fool’s Gold. “It really felt like a statement beer for us,” he said.

With foraged and local ingredients top of mind, Balance Brewing sometimes has to shift and sway with whatever direction the wind blows.

They couldn’t get a hold of apricots this year, so the beer took a hiatus. But Horrocks hopes to bring it back soon.

One beer that did work out successfully, becoming one of Balance Brewing’s best-selling, includes different varieties of mushrooms.

Working with Polyspore, a local mushroom producer about twenty miles outside of Manchester, Horrocks and Harris experimented putting both dried and fresh fungi into beer.

“It was pretty wild,” he said. “The idea was exploring umami in beer.”

Horrocks says they started by steeping mushrooms to essentially make a mushroom stock, adding about a kilo of dried mushrooms to a 100-liter batch. “So it was not an insignificant amount of mushrooms.”

The pair settled on Lion’s Mane and Freckled Chestnut.

“Lion’s Mane, in particular, doesn’t have a huge character. In fact, it kind of weirdly goes towards vanilla and citrus,” said Horrocks, who wants to try a version with a “really mushroomy mushroom” like porcini or shiitake. “But [Polyspore] doesn’t grow them.”

After spending around nine to twelve months in used red-wine barrels, the mushroom saison really “captured the imagination of the people,” laughed Horrocks.

When I visited, they were already on their second batch. The intrigue behind this beer could keep it in the rotation in the future.

It’s All in the Name: Balance Brewing

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

No matter how far Horrocks and Harris stretch the boundaries of beer and our imaginations, every batch comes back to one word.

“It’s kind of in the name,” said Horrocks. “We want the beers to be balanced.”

Horrocks paused, thought for a second, and revised. “We want to make funky, complex, acidic beer that is balanced.”

A nod you’ll find right in the logo, a barrel with staves running through it to make it look like a “B”. Harris and Horrocks first sketched the designst on a piece of paper. “It’s a balanced logo,” he told me with a twinkle.

I asked Horrocks if he still had that paper with the original sketch.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

His answer seemed to fit everything about Balance perfectly, bouncing from no to “Well, maybe somewhere. Not that I know of. Yeah, it could probably be in a pile somewhere.”

Even the barrels piled in the back, essential to Balance Brewing’s blending and aging, showcase dichotomy.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

As we walked around the concrete archway, Horrocks pointed out all of Balance Brewing’s different vessels. For instance, one hundred pristine wine barrels from Bordeaux made of French-American oak. Steamed and reconditioned, these vessels have been so crucial to the consistency of Balance Brewing’s beers. “Just look at them; they look almost new. The quality of the wood is just amazing,” he beamed. “I don’t think we chucked a single barrel away.”

Across the room, he showed something slightly different—eight whiskey barrels. “Just look at how relatively gnarly those are,” he laughed.

Horrocks bounced around as we talked, pointing up to a far corner of the archway where old, tan Brazilian coffee stacks hung, plump with aged hops from 2017.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Standard for producing Lambics, the three-year-old aged hops go into some of Balance Brewing’s beers.

“They’re proper hay smelling now, but they had a cheesiness in the first year or so,” said Horrocks.

They get the sacks for free from a local coffee company. “We’re basically recycling them,” he explained. Whether he meant the hops, the bags, or both wasn’t precisely clear. “We just give [the coffee company] a few bottles when they’re ready!”

Fining and refining. Like an unsettled scale tipping in the wind, Balance Brewing moves up, down, back, and forth, constantly pursuing that one moment of equilibrium.

Much like Horrocks himself. As we walked back to the taproom, a silent, errant thought pulled him away. When I looked back, I saw that he had climbed up onto a shelf and appeared to be trying to get into a giant drum.

“I basically got a sort of hard lid, no pressure release valve. And when I moved it up here earlier today, I put it on tight so it could splash about or whatever, and I need to just loosen it a bit,” he explained. Full of beer aging on raspberries, Horrocks worried the refermentation inside could blow the lid.

After several failed attempts, he told me not to worry, that he would take care of it later. There was more Saison De Maison we needed to finish drinking in the taproom.

As we drained our glasses, gleefully chatting about the electrifying pineapple character, he turned to me and said, “It’s one of our favorite pleasures. Having a balanced beer.”

At Balance Brewing, the Possibilities Are Endless

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

“We’re still quite young as a brewery, and we’ve still got a lot of ideas and experiments we’re yet to try out,” noted Harris. “The possibilities are pretty much endless, and we’re excited to find out how our beer’s complexity develops over time.”

This year, Balance Brewing will celebrate it’s third birthday. Although, the current taproom in the “Beermuda Triangle,” as it’s called, has only been open for eight months.

“It’s been amazing to create a space where people can enjoy our beers,” said Harris. “We’ve created something different…and we’ve really found our place.”

As I walked out into the Manchester night, I left Horrocks much like I’d found him: diligently working in the back. He had an hour and a half left of things to do—get some hops in the tank, transfer some beer, and figure out how to release the pressure on those damn fermenting raspberries.

“Don’t worry,” he messaged me later. “I did manage to sort the lid out :)”

Sounds like despite the chaos, everything balanced itself out in the end.