Shop

From Fjords to Fermentation: How One Family Built Iceland’s First Craft Brewery

Iceland's first. Family first.

Like This, Read That

The road stretched out before us, a long, thin paved line disappearing into the horizon. An optical illusion drawing us nearer to two monstrous, snowcapped mountains, the road seemed to be taking us somewhere we’d never reach. Out of the vast expanse, a mock whale tale appears out of the ground. Next to it, a tiny sign reads ‘Bjórböðin Beer Spa and Kaldi.’ We turn.

There are three of us in the Suzuki Vitara, a rusty tin can whose back doors only stay open if you hold them. At the wheel, renowned beer author Tim Webb, and next to him, CAMRA member Michael Collard.

We’ve been traveling around Iceland’s Ring Road for seven days, attempting to visit every single brewery in Iceland. Which is how we find ourselves four and a half hours from Reykjavik in a village on one of the longest fjords in Iceland that’s really just a cluster of houses, a ferry port, and one brewery.

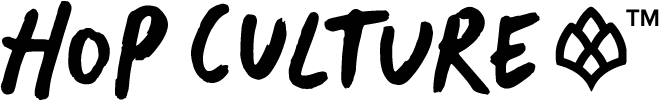

As we pull up, a short, stocky, red-haired man greets us boisterously. “Alright, guys, welcome to Kaldi. My name is Siggi,” he says energetically while introducing us to his sister, Esther, and mom, Agnes, whom he calls the “big boss.”

Started by Siggi’s parents almost two decades ago, Bruggsmiðjan Kaldi is a “family business,” as he tells us.

But Kaldi is more than just a collection of family members. In what seems like the middle of nowhere, in a place 250 miles (402 km) from Iceland’s capital, this building became the first-ever craft brewery in Iceland.

At Kaldi: Czech Roots, Iceland Inspiration

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

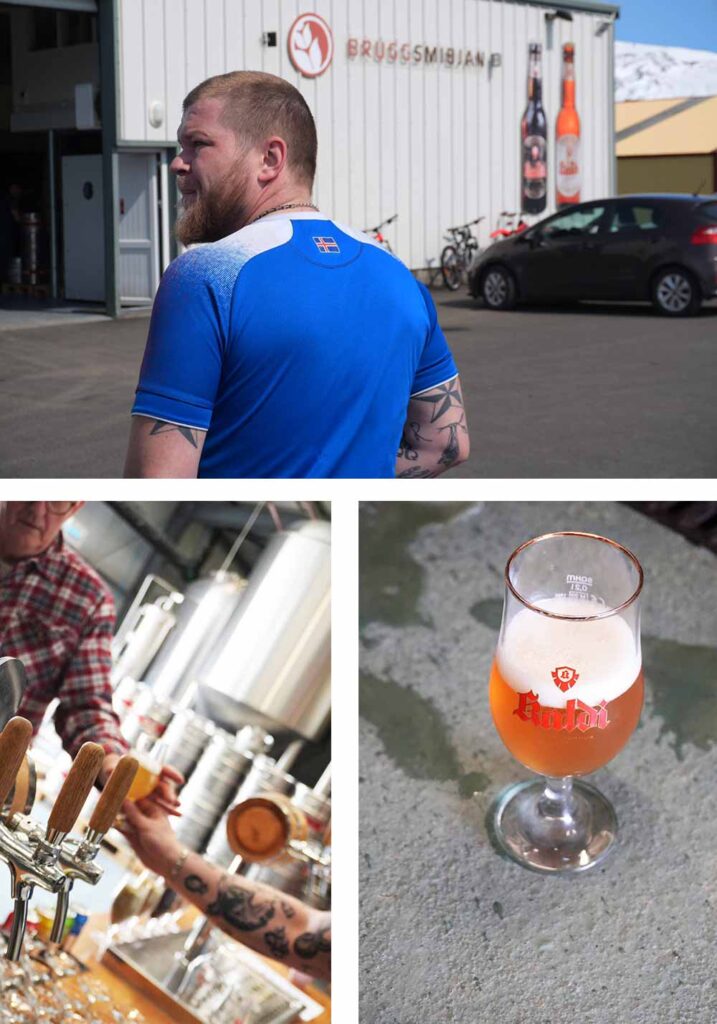

Before we meet more of Siggi’s family, he steers us to the bar. “Could I start you off with some beer?” he says proudly.

Swiftly grabbing a glass, he pours us each some clear, amber-gold liquid. “This is the first beer we brought to market,” explains Siggi, whose full name is Sigurdur Bragi Olaffson. He learned the recipe from Kaldi’s first brewmaster, David Masa, when he turned sixteen.

Siggi moves and speaks with purpose. Kitted out in a bright blue vintage Errea Iceland national men’s soccer team jersey, Kaldi’s brewmaster moves like he’s playing, darting confidently from one thing to the next.

As he sets down the branded tulip glass in front of us, he explains that the beer called Ljós means “light” in Icelandic.

The Czech pilsner has a pleasant maltiness that borders on nuttiness, which Siggi attributes to the single decoction process (a method of drawing off a set volume of malt from the mash and boiling the cracked grains). “It brings out more Maillard reaction, the caramelization into the beer,” he tells us.

This is the beer Siggi trots out first, like his prized fighter. When a couple walks in randomly during our visit, they ask Siggi about his favorite. He responds without hesitation, “I always like to start people with our Czech Pilsner.”

Czech influence runs deep at Kaldi, whose brewhouse was built in Czechia by Paul Holborn, an American brewing pioneer who designs brewing systems for breweries around the world. “He built this system for us to do decoction mashing,” says Siggi, pointing one fully tatted arm behind him to the gorgeous, gleaming copper brew kit.

Without a doubt, this is the focal point of the brewery, almost like a shining lighthouse in the vast starkness of the Icelandic landscape.

Siggi shows us each piece, from the lauter tun to an unconventional piece called the wort receiver, which, during decoction, collects wort in the lower half, allowing Kaldi to start a second brew in the mash tun.

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

“It looks fabulous,” comments Webb. “That’s what you want a brewery to look like.”

Although they clean it every week, Siggi says, “It’s never clean enough for me.”

The 10-hectoliter brew house was designed to produce a maximum of 350,000 liters, but Siggi notes that at Kaldi’s peak, they brewed closer to 700,000 liters per year. Since the global pandemic, they’re closing in on reaching 600,000 liters.

Water Water Everywhere, Now a Drop to Drink

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Siggi and his family live and grew up surrounded by water. It’s everywhere you look.

Sitting in the brewery’s breakroom around a table of sheet cake and sandwich rolls, remnants of a family confirmation celebration, we look out through a large window to the sparkling Eyjafjörður Fjord.

In the front of the brewery, Siggi points to the left side of Krossafjall mountain. Nicknamed Sólarfjall (or sunny mountain), “the reservoir there is the water that feeds our town and also the brewery,” he explains.

And this life-saving liquid in this family’s veins.

Born and raised in the area, Kaldi Co-Founder Agnes Anna Sigurðardóttir grew up in a fishing family.

“My great-grandparents, my grandparents, and my parents,” says Siggi, “all worked in the fishing factory, worked the boats.”

Siggi’s father moved to the area when he was sixteen to work as a fisherman. He spent twenty-seven years fishing until a bad accident in the spring of 2003 ruined his left knee.

“If you lose a leg,” says Siggi, “you can’t work at sea.”

The couple, then with four children, had to make a decision. Move or come up with a new idea.

Two years later, Agnes saw a story on TV covering the growing popularity of microbreweries around Europe.

“She thought, hey, let’s make beer,” says Siggi.

Well, actually, as Agnes explains in Icelandic, she thought first about the village’s water.

“The water, water, water!” she shares while Siggi translates. “Always respect that privilege to have good water.”

It’s a belief that Agnes’ grandmother taught her, constantly nagging her to turn off the faucet while brushing her teeth.

Here, water was always precious.

Having lost her grandmother a few years earlier, Agnes felt that when she saw the news program on TV, her grandmother was talking to her.

At this point, Agnes gestures emphatically and laughs.

“She doesn’t want you to think she’s mad,” Siggi translates, “but that moment had never happened before.”

Overcome, Agnes rushed out to tell Siggi’s dad, who was mowing the lawn. “I know what we can do,” she says. “We can make beer; that’s the perfect way we can use the water!”

While Siggi’s dad just laughed, Agnes called her grandfather, who told her it was a great idea.

“If he had said something else,” says Agnes, “I don’t think we would be here right now.”

Without any knowledge of beer making or any money to open a brewery, “She just went headfirst,” says Siggi.

Jumping Headfirst Into Kaldi

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

To start, Agnes contacted the news program and discovered the name of one of the Danish breweries featured. The pair decided to travel to Denmark.

“Just getting a babysitter for the kids while they went,” says Siggi, “was a big pain for them.”

She went to that brewery and asked, “Can you help us take the next steps?” Siggi tells us.

They encouraged her to make a Czech pilsner. “The few breweries we went to talked about Czech beer and Czechia,” says Agnes. “They seemed the most confident.”

After returning home, Agnes and her husband went to a liquor store and bought all the German beers and Czech pilsners they could find.

“They were the most fond of the Czech pilsners,” says Siggi.

So, they contacted the Icelandic ambassador in Czechia, Þórir Ólason, and arranged a trip.

“They could barely speak English,” says Siggi, “but somehow they managed.”

During that visit, they met David Masa, a freelance brewmaster who went from country to country setting up breweries. He came to Iceland and spent the first two and a half years developing the first recipes. “Teaching us the dos and don’ts,” says Siggi.

The idea seemed wild, opening up a brewery in the middle of nowhere.

Agnes and her husband put everything on the line, including their house, their parents’ houses, and their car, just to finance the business. “Everything was under for the business,” says Siggi.

It’s why Siggi’s brother, Þorsteinn Hafberg (called Steini), came up with the name Kaldi.

Although it has several meanings, including cold in Icelandic and to reference a special forecast for weather out at sea (a slight nod to the family’s fishing history), Kaldi is part of a saying in Iceland that means, “you’re doing something stupid but brave at the same time,” says Siggi.

Which is what the family thought Siggi’s mom and dad were doing when, in September 2006, Kaldi officially became the first craft brewery in Iceland.

Family First at Kaldi

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

After speaking with Agnes, Siggi wants to show us Kaldi’s IPA. Still in the tanks, he says it’s not quite ready, but wants to give us a pour.

We walk into one of the brewery’s attachments, a room built off the original building that now houses seven fermenters. “Mind the hoses,” he cautions us as we step over lines snaking across the ground.

Pouring us a fresh pull from the pigtail, he warns us it’s a little undercarbonated.

“It’s beautiful,” says Webb.

Siggi counters, “It’s a little bit green.”

Much like Siggi when he first started helping out.

Only thirteen when Kaldi opened, Siggi, his older brother, and younger sister helped where they could, during bottling or brewing. When he had breaks from school, Siggi would learn how to brew and spend time in the business.

But by his own admission, he wasn’t always serious about joining the family legacy. But, after dropping out of college and moving back from Reykjavik, he expected to start working at the brewery immediately.

“My mom said there’s no job for you here,” laughs Siggi, who worked as a fisherman for three months before his mom would officially hire him.

“It’s not automatic,” says Siggi. “It was harsh, but I learned something from it: Don’t take it for granted.”

At Kaldi, you aren’t just grandfathered into the business.

“There needs to be respect,” says Siggi. “It’s not given.”

While Siggi’s older brother handles the forklift, bottling, and canning, his younger brother is a full-time fisherman and only occasionally helps out. “It was not his path,” says Siggi, who has three kids, but says he won’t push them one way or the other.

Siggi’s son likes to cook and bake, so he’s not sure he’ll join the brewery. But his daughter, also named Agnes, might.

And it goes beyond the family itself. In a village with only 110 people, Kaldi employs ten percent of the population, often hiring teenagers to work over the summers when they’re off from school. He introduces us to each one as we walk through the brewery.

With each new person we meet, it’s almost as if Siggi is welcoming us into his family.

Beer here isn’t just liquid in a glass; it’s a story of one family.

From Pilsners to Þorri: The Seasonal Spectrum of Kaldi Beers

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Siggi only took over as the brewmaster a few years ago.

He had to prove himself, earning his Brewmaster diploma at the Siebel Institute of Technology and traveling to Czechia twice to apprentice with Masa.

Which is another reason why you’ll see Czech, German, and continental European influence in Kaldi’s beers.

Kaldi follows the Reinheitsgebot (German Purity Law), which states that beer can only be brewed with four ingredients: water, barley, hops, and yeast.

All but two of Kaldi’s beers follow these regulations. “That’s a big deal for us,” says Siggi.

All of their two-row floor-malted barley comes from Raven Trading in Olomouc, Czechia.

Siggi considers the grain a significant factor in the flavor of the beers at Kaldi, which he calls better for decoction.

Kaldi offers six year-round beers: Kaldi Ljós (Czech Pilsner), Kaldi Dökkur (Dunkel/Dark Pilsner), Kaldi IPA, Kaldi Lite, Kaldi Neipa (New England IPA), Kaldi Belgískur Tripel, and Kaldi 0,0% NA beer.

But Siggi likes to sneak in a specialty beer every couple of months.

To complement the Czech pilsner, Kaldi Ljós, Siggi makes Kaldi Dokkor (which translates to dark in English).

“I call it a dark pilsner,” Siggi explains, “because not many people know the word dunkel.”

Starting with a base malt of fifty percent Pilsner, fifteen percent Munich, and fifteen percent Caramalt, Siggi also uses caramel and chocolate malt.

The grist gives this beer a distinctly treacle texture, complemented by notes of German Black Forest cake—chocolate and cherry. Without leaning too hard into the syrupy or sweet world, Dökkur finishes crisp and clean like a fizzy Dr. Brown Black Cherry pop.

On the specialty side, when we visited, Siggi had a summer special on tap. Kaldi’s Belgian witbier features orange zest added at the end of the boil.

“I want to double the amount,” he tells us, referring to the next batch, upping the amount from two to four kilos.

Siggi uses Czech Sladek hops for bittering (which he wants to tone down in the next batch) and Citra for the aroma.

“This one’s the tastiest wheat beer I’ve had for a long while,” says Webb after taking his first sip.

Agnes agrees; she loves this beer.

Her other favorite is a winter seasonal called Þorra Kaldi, a 5.6% ABV hoppy lager enjoyed during Þorri, the coldest months of the year, January to March. Þorri is the season when Icelandic people gather at festivals to eat traditional foods (such as fermented shark, sour whale, and ram testicles) and drink a variety of alcoholic beverages.

Siggi takes Þorra Kaldi through a decoction mash and always features three hops, switching them up each year. For the last batch, he used Fuggles, Cascade, and Nelson Sauvin.

Soaking in Success

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Despite being in the middle of nowhere, Agnes tells us that Kaldi receives between 15,000 and 18,000 visitors a year.

They come not only for the beer but for the Beer Spa.

Unsurprisingly, the family’s entrepreneurial matriarch came up with this idea as well, after visiting a beer spa during one of her trips to Czechia.

“She said she’d never felt her skin, her hair [feel so good],” says Siggi. “She wanted to open up the first beer spa in the Nordic countries.”

Siggy bought the building that now houses the beer spa when he was nineteen, planning to build his own house on the property.

But when Agnes came up with the idea, he built a beer spa instead. “With the help from a lot of good people,” he assures me.

An entire experience, the Beer Spa includes a dip in what they call “hot pots,” or hot tubs overlooking the fjord.

We’re lucky, the manager of the Beer Spa tells us, as we gazed at perfectly white-capped peaks. The fresh snow came down just a couple of days earlier. If we’d been here last week, we’d be looking at dirty mountain tops.

The main show, however, is inside. The manager shows us each to a private tub filled with young lager, the Kaldi Ljós that hasn’t fermented for as long as the one we drank hours earlier.

Next to each tub is a private tap, giving you unlimited self-pours of Kaldi’s Czech pilsner.

“This is your day to relax,” the attendant tells us as we slip into that warm mixture of young lager, hops, yeast, and bath products.

Amongst the aroma of freshly baked bread and lavender soap, we soak and sip, emerging from the tubs fresher, cleaner, and definitely a little less sober.

The Beer Spa is just one more example of the steadfast foundation Agnes has built.

“She’s a strong woman,” says Siggi.

A Family Toast: Twenty Years and One Big Beer

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz, Hop Culture

Before we leave, Siggi has one last beer to share with us. It’s almost bigger than the mountain outside his door.

The barleywine was an idea from Kaldi’s Brewer Jacob De Jager. Agnes usually sets the brewing schedule, but three years ago, the Dutchman says he saw a question mark on the brew day. “I asked Agnes, what’s with the question mark?” says De Jager, who ambles over to drink with us. “She made a stupid mistake and said you guys do something!”

That something was a 12.5% ABV barleywine.

Because beers are taxed based on alcohol percentage in Iceland, Agnes was not amused.

“She’s never done that since,” laughs De Jager.

Built with Pilsen, Munich, caramel, and carafa Special malts, Kaldi’s Barleywine has become something of a special beer.

When Kaldi celebrates its twentieth anniversary next year, Siggi wants to brew a version of this barleywine.

“We’re going to get my mom to sign each bottle,” he says.

As we sip on the lovely, rich ale full of flavors of roasted chestnuts and stewed fruits, Siggi’s father walks by; he briefly introduces us.

“Now you’ve met the whole family,” Siggi smiles, looking out his front door at a range of pristine peaks, the same that give Kaldi the water it needs to brew.

“It’s like looking at a painting every day,” he says wistfully.

As we walk out into that picture-perfect postcard, heading to the Beer Spa for lunch, Siggi calls after us. “If you want to come get some beers for the hotel after lunch,” he shouts, “we’re going to be here until ten this evening.”

It’s almost like we’re a part of the family now.

Almost.