Shop

Sacred Herbs and Fermented Lore: The Rise of Pagan Brewing at Labietis

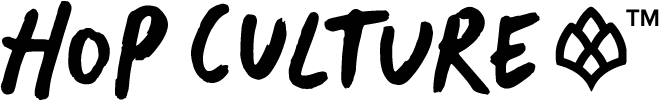

Pagan brews.

Like This, Read That

Beer, Birch, and Baltic Grit: The Legendary Evolution of Põhjala

At Salama Brewing, Lightning Does Strike Twice

Hop Culture traveled to Riga, Latvia with Brewtopia, which gives folks the backstage pass to breweries, pubs, and beer-centric restaurants in countries all over the world! Want to travel to these places like we did? Check out Brewtopia’s upcoming beer trips!

I untwist the jar, inhaling a strong, sweet scent similar to vanilla candles and my mom’s nightly ritual of tea and honey. “This would be meadowsweet,” Labietis bartender Roberts Laķis tells me, pushing another jar of dried leaves across the table. A quick whiff from this clear cylinder reminds me of rye, with a hint of herbaceousness and a spicy pungency. “This would be yarrow,” he explains.

Above my head, bushels of what appear to be dried flowers dangle from the ceiling like lamps.

This is Labietis’ light. Two of the most popular botanicals that Labietis uses in its beers, meadowsweet and yarrow, are just a small part of this funky brewery’s philosophy.

I’ve come to the Latvian brewery in the country’s capital on a slightly rainy afternoon in June. For the past week and a half, I’ve visited one of the hypest breweries in Helsinki and one of the highest-rated ones in Tallinn, Estonia.

But here, at a brewery making self-proclaimed “Pagan Brews” (more on that later), I find something completely different.

Labietis trades hops for herbs, beer trends for botanicals, and formalities for folklore.

Founded in 2013 by Reinis Pļaviņš and Edgars Melnis, Labietis emerged from a humble circle of homebrewers to become Latvia’s first modern craft brewery. But rather than follow the playbook of American IPAs or Belgian saisons, Labietis wrote its own—pulling from Latvian folklore, ancient fermentation techniques, and the literal fruits (and herbs) of the land.

At Labietis, beer is more than a beverage. It’s a living history lesson, a foraged experiment, a cultural revival in a glass. If hops are the symbol of beer’s modernity, then Labietis is its mythology—wild, local, and entirely its own.

From Kitesurfing to Homebrew Kits

Photography courtesy of Labietis

A former kitesurfer, Labietis Co-Founder Reinis Pļaviņš was living on the beach when the 2008 economic crisis hit Latvia.

“I looked around at which of my hobbies looked like money,” he joked. “I had just started homebrewing.”

A somewhat underground hobby, homebrewing in Latvia only gained popularity recently, in the early 2010s.

And it was small.

Pļaviņš describes the scene as a bunch of guys sitting around a table drinking each other’s homebrews and talking shop.

I joke with him that in my head, I’m picturing the classic Cassius Marcellus Coolidge “Dogs Playing Poker” painting.

He doesn’t think that’s too far off.

Resources were scarce.

He tells me that you couldn’t even buy the right ingredients in Latvia, so you had to go to nearby Lithuania instead.

His first recipe he found on a culinary platform from a guy named Edgars Melnis (remember that name).

When I asked Pļaviņš what he brewed, he responded, “German hops, single-malt, general-purpose cider/beer/wine/mead yeast, judge for yourself!”

However, as with any hobby, those who did it more often became better and better.

“From the guys who were sitting at the homebrewers table at the beginning,” he shares, “I think now six or seven are breweries.”

But at the time, craft breweries didn’t even exist.

By 2012, Pļaviņš had won a homebrew competition with his recipe for an English bitter called Soho Švītiņš. Pļaviņš called the ESB recipe basic but with a couple of tweaks—some Vienna base malt and Galaxy late hop additions.

The win gave him confidence.

“If I can brew an English bitter,” he told me, “I can brew anything.”

So he went all in.

One night while he sat drinking with those other homebrewers, he stood up and blatantly said, “I’m going to open a brewery, I’m about thirty thousand short, maybe someone wants to join me.”

One of the others at the table, Melnis (yes, that same one), told him, “Let’s meet tomorrow sober.”

After a ten-minute meeting over lunch (the longest meeting they’ve ever had, according to Pļaviņš), the two agreed to start Latvia’s first craft brewery.

But not just any old craft brewery.

Pagan Brews

Photography courtesy of Labietis

Pļaviņš thinks of himself as a bit of a white sparrow.

He’s speaking to me from the inside of a van that he tells me is at a yacht club. His golden brown hair flows luxuriously down to his shoulders.

When he speaks, it’s with wisdom, as if he’s a man who has lived, has seen, and wants to share his knowledge with the world.

Our conversation often veered into history, folklore, and tales, which he shared not with pretentiousness but with patient kindness and a dry sense of humor.

Pļaviņš is just cut from a different cloth, and that always translated in his beers, which often featured ingredients he could find around him—yarrow, meadowsweet, and heather, for example.

He recalls others laughing behind his back. But he didn’t care.

“I didn’t understand the hype around Citra when it appeared,” he laughs in a gesture that’s somewhat ironic because, over a decade later, Labietis is still going strong, all with those “laughed at” beers.

Pļaviņš and Melnis sum up Labietis in two words: pagan brews.

What does that mean?

“You are most likely clueless,” Pļaviņš says matter-of-factly. “So, for the unfortunate 99.9% of the world that doesn’t speak Latvian, we made a slogan that describes what we do.”

To understand its slogan, you first had to understand the brewery’s name.

Labietis refers to a warrior in pre-Christian Latvian society.

Pļaviņš and Melnis wanted to capture this idea of living before being bound by boring rules and regulations, often governed by a religion.

Photography courtesy of Labietis

Photography courtesy of Labietis

“We’re the noble savage who lives in his meadow of flowers and untouched forests without the sounds of the bells of the church on Sundays,” Pļaviņš explains.

If Christianity is hops in this scenario, then Labietis is pagan, incorporating what grows around them.

“I think the closest thing is using the word terroir,” says Pļaviņš.

He clarifies, “It’s not that we hate hops. It’s just that, if you are here in Latvia, there is so much more than hops that you can add to beer.”

Different types of herbs, berries, and honeys, just to start.

When you walk into the taproom about ten minutes outside of Riga’s city center, you won’t find dried hops hanging on the ceiling, but dried plants.

“We’re like a pagan pharmacy,” says Roberts Laķis, who has worked behind the bar at Labietis for the last year. “A place where you could get a drink with some medicinal properties.”

Labietis challenges you to think beyond the borders we’ve placed on beverages. Hops and barley don’t always mean beer. Cider isn’t just from apples, and mead isn’t only from honey.

Photography courtesy of Labietis

“I’d argue that if we go half a millennium backwards, you’d be drinking very interesting drinks,” shares Pļaviņš. “People were basically dropping everything into a brew that was not poisonous!”

At Labietis, this translates to beers with juniper, braggots featuring lingonberries, cranberries, bog myrtle, meadowsweet, and linden blossom, as well as meads made with honey, bee pollen, and heather.

Pļaviņš estimates that over the last decade-plus, they’ve brewed with thirty different herbs (that aren’t hops) and ten or more berries and fruits characteristic of the Baltic Sea region.

“We’re taking inspiration from classic styles of beers, as well as ancient brewing traditions here in the Baltic States and combining all of these traditional beer-making techniques with some more modern styles,” sums up Laķis.

The idea isn’t augmentation and aggression, but niche and nuance.

In the States, progression in craft beer often meant more, more, more. It’s what gave us the IBU wars of the early 2010s, which saw breweries pushing the limits of bitterness in beer to the point of no return and, well, no taste (though there was undoubtedly some taste, but it wasn’t pleasant).

“It’s like boxing with tied hands,” Pļaviņš sarcastically says to me. “Of course, you can get inventive. You can put three times more hops, four times more hops, or five times more hops. Then you can get really crazy and put six times more hops.”

To Pļaviņš, that’s not ingenuity but iteration. That’s still playing in a two-dimensional field on a linear scale.

With Labietis, beers have complete freedom, untied from German Purity Laws or hyped-up trends.

These are beers not only with a sense of place, but with a sense of time.

The Home of Herbivores

Photography courtesy of Labietis

Photography courtesy of Labietis

Growing up in Eastern Europe, Pļaviņš says every family dabbled in traditional herbal healing.

“We have been unlucky enough to have pretty crappy health care,” he laughs. “Compared to Western Europe, we are all shamans.”

Walking around in nature, Pļaviņš remembers just picking things up, smelling them, and taking them home to brew a tea. (What he would consider today, a great pilot brew).

Although, he also thanks a period of over fifty years (from 1940 to 1991) of Soviet occupation for the Latvians’ obsession with cultivating and using what is around them.

“Everyone was on their own,” he recalls. People would make their own jams for winter and teas because they couldn’t buy them in the store.

“Even nowadays, when you open up a cupboard, every Latvian person has a jar of something,” he says. When I asked what we’d find in his cabinet right now, he wavers, noting that last year’s herbs are pretty much gone before spouting off a grocery list of tarragon, wormwood, linden blossom, pine shoots, dragonhead, and wild oregano in his cupboard. “My favorite tea mix is wild mint and linden blossom,” he adds.

This is the soul of Labietis, a cupboard of foraged ingredients in your glass.

Drinking in the Land of Latvia

Photography courtesy of Labietis

When I visit on a grey afternoon in June, a menu of colorful planks that look almost like skateboard decks greets us.

Everything on the menu piques curiosity—gin barrel-aged juniper red ale, second-hand mixed-fermentation grape saison, herbal berry lemonade, herbal brown ale, mixed-fermentation braggot.

The only thing that looks “conventional” is a double dry-hopped pale ale (a relatively new addition, Pļaviņš would tell me later).

As Pļaviņš says, these are beers with terroir.

When I sit down with Laķis to chat, he brings over jars of dried meadowsweet, yarrow, and heather, opening them so I can smell the contents.

“The aroma of meadowsweet triggers the brain into perceiving any drink as sweeter than it is,” he explains as I take a sniff. You can call meadowsweet a natural sweetener of sorts.”

Yarrow, on the other hand, he explains, is known for its bitter properties.

These are the building blocks of Labietis. Not Citra, Galaxy, or Hallertau Mittelfrüh. But the things people used before they even knew about those little green cones on the bine.

Labietis embodies this philosophy.

Photography courtesy of Labietis

“We have this inner code of ethics,” says Pļaviņš. “If we name an ingredient on the label, we will use it in its purest natural form.”

No extracts here. Just Pļaviņš and Melnis messing around, trying to determine the perfect ratios.

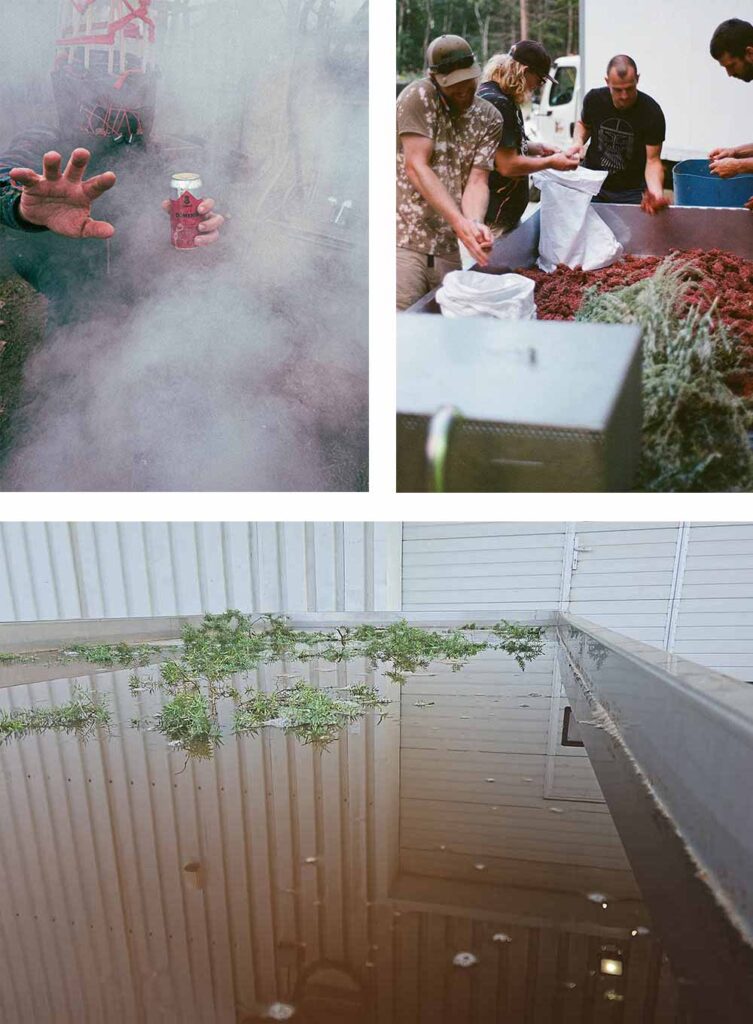

For that reason, Pļaviņš jokes that Labietis probably has “one of the largest hopbacks in the world for the size of our brewery.”

It’s how they infuse their beers with these different herbs.

Experimentation has taught Pļaviņš that most mellow herbs—yarrow, meadowsweet, and chamomile—can be added at one to three grams per liter in the boil.

But that’s not a universal rule.

“Do you have Linden trees?” Pļaviņš asks me several weeks later when I’m back in the States, and we’re catching up over Zoom.

“I don’t think so,” I respond, “but I could be wrong.”

When in full blossom, a Linden tree expresses sap that’s “sticky, sweet, and like a piece of nectar,” he says. Non-fermentable, the sap is sweet enough to basically use in place of lactose.

But to truly extract the flavor, you need a lot of it—about seven grams per liter, according to Pļaviņš, who spouts off these ratios with ease.

Wormwood, too, can be quite tricky. Perhaps best recognized in the States for its cultural significance in Malört, wormwood should be used at a concentration of 0.05 to 0.08 grams per liter at flameout (the moment when heat is turned off at the end of the boil).

A lesson Pļaviņš learned the hard way.

“I started with one gram per liter,” he remembers. “That’s the only beer that I have ever poured out.”

Pļaviņš described the beer as so bitter that it was undrinkable.

Small amounts give a pleasant grapefruit bitterness, but overdo it, and Pļaviņš says the flavors quickly go from “grapefruit to stomach acid.”

I’d argue Malört should maybe take note of this rule (don’t come after me, Chicagoans. I lived in Chicago for six years and drank plenty of Malört, but I’m just saying, it’s not the tastiest thing I’ve ever put in my mouth).

Back in Labietis’ taproom, after much debate, I settled on the juniper red ale. It’s one of the first beers Labietis released when the brewery launched in August 2013.

Imagine that. Instead of starting Latvia’s first craft brewery with something crowd-pleasing and hoppy like an IPA, Pļaviņš and Melnis dropped things like an herbal blonde ale and a juniper red ale.

A Juniper Red Ale

Labietis’ best-selling beer for nine years, Mežs, which means forest, is a red ale brewed with juniper berries.

Pļaviņš points out that people have a history of brewing with juniper, often referenced in local folksongs or found in styles like the Finnish Sahti, an unfiltered, unpasteurized tart, traditional farmhouse ale flavored with juniper instead of hops.

Where a traditional Sahti uses juniper twigs as a filter for the mash, Labietis’ original Irish red ale experimented with the juniper berries.

“Basically, those are the pine cones,” Pļaviņš explains. “So they have a lot of resin in them.”

The berries give this Irish red ale a bit of everything. “It’s a bit sweet, sour, resinous, refreshing,” says Pļaviņš. “It’s right in the middle.”

I ordered this beer first because I’ve read that it’s one of Labietis’ flagship beers.

Pouring almost like a burnt honey, the red ale drinks with a low carbonation and honeyed sweetness. Paired with a red currant-like tartness, Mežs is a great introduction to Labietis’ pagan brews.

Buzzing Beehives to Bronze Age Braggots

Photography courtesy of Labietis

Pļaviņš is also particularly proud of Labietis’ award-winning meads and braggots, both of which find inspiration from folk songs, mythology, and history (I’ve taken to calling this folk fermentation).

Several stories exist about the world’s first fermented beverage. Pļaviņš tells me one he’s heard about a fallen beehive during a storm that fills with water and ferments.

Today, we know these fermented honey beverages as mead.

In Latvia, Medstāvis (stāvēt means to stand/keep, according to Pļaviņš) refers to a historic drink that involves placing honeycomb in a barrel buried underground for a prolonged period.

During the eighteenth century, Pļaviņš says people would find these hives in the forest, take them back to their village, drop them in a big cauldron, and ferment them.

“You’d basically take the honey and tell the bees to get lost, try to make another hive, I’ll be back next year,” he says. “On the third or fourth day, you push the bees away from the top and drink it.”

Labietis’ Zintnieks mimics this drink. Considered a whole-hive mead, Zintnieks includes honey, bišu maize, fowl’s milk, yeast, water, bee pollen, and heather.

The latter refers to a plant that, in full blossom, has a white fungus growing on it, which, according to Pļaviņš, has a chemistry similar to LSD.

According to both Ancient Roman chronicles and Scandinavian legend, when the Romans fought the Picts, an ancient people who lived in what is today considered Scotland, the Picts drank heather before battle to give them strength.

“Basically, the Romans were fighting guys who were just high,” laughs Pļaviņš.

“So, there is natural LSD going into this mead now?” I jokingly ask for clarification.

“Kind of, yeah,” Pļaviņš says with a small grin.

Laķis assures me, “Our beer doesn’t have psychedelic properties!”

For what it’s worth, I had a chance to try this mead…and I can report no hallucinogenic effects.

What I can say is that it was an excellent mead, washing over your tastebuds with layers of heathery bee pollen and propolis, a sort of resinous mixture of beeswax, tree resin, and other botanicals.

In addition to a line of meads, Labietis also dabbles with braggots, a sort of beer-mead hybrid.

In particular, both Pļaviņš and Laķis point me to Labietis’ Bronze Age braggot called Gaismas Ragana (Witch of Light). The culturally complex liquid draws inspiration from the Egtved Girl, an archaeological discovery dating back to approximately 1370 BC, whose contents give glimpses into life during the Bronze Age.

The well-preserved remains of a girl in a coffin found outside Egtved, Denmark, provided numerous clues, including the types of beverages people consumed at the time. Tests on a buried cup revealed the presence of various pollens, herbs, and berries, which Labietis used in the recipe for Gaismas Ragana.

For the sugar, Labietis includes lingonberries, cranberries, honey, and wheat. And for the bittering, bog myrtle, meadowsweet, and linden blossom.

“Because of its sweet qualities and quite a balanced taste, the profile in general, it’s a perfect balance between sweet and sour,” says Laķis, who fell in love with Labietis after first trying the brewery’s braggot when he turned eighteen.

Photography courtesy of Labietis

At this point, I’ve made my way through Labietis juniper red ale, hallucinogenic standout mead, and historical braggot, so I ask Laķis for his opinion.

What should I drink next?

He recommends Zilgas Humpalina, a second-hand mixed-fermentation grape saison.

Not your typical grapes, but small, dark ones that typically grow around Latvian lawns, says Laķis. “They became quite popular in the Soviet times as a way to add some greenery.”

In Latvian, Humpala is shorthand for second-hand shops. During the ‘90s, “people thought we needed help, so there was a lot of humanitarian aid,” explains Pļaviņš. The secondhand reference refers to how Labietis reused Latvian grapes to make a second beer.

Pļaviņš explains how they initially used the grapes to brew a one-off mixed fermentation beer. They had planned to discard the grapes, but a visit from the folks at Garden Path Fermentation in Washington state changed their minds.

“Two or three summers ago, we were pouring off the first mixed fermentation from the berries, and they were like, ‘Oh, cool, now you’ll be able to make another two or three beers out of the berries … drop something fresh on it and see what happens.’”

So they did.

Labietis dropped a fully fermented saison on the second-use Latvian grapes to make a stunning yet subtle saison.

“It’s a beautiful, easy-drinking beer that’s a bit dry, a bit sour, and a bit fruity,” says Pļaviņš.

For me, it was one of my favorite beers from Labietis, and truly emblematic of what they do.

Not only was Labietis the first, but it’s the second, the third, the fourth. This brewery is like a Matryoshka doll; there’s always another surprise waiting inside.

And that’s something they never lose sight of.

The Privilege of the Past, The Freedom of the Future

Photography courtesy of Labietis

It’s been over ten years since Pļaviņš first stood up at that homebrewing table and declared he wanted to open a craft brewery.

Considered the first of its kind in Latvia, Labieties went into the market “like a hot knife in butter,” says Pļaviņš.

They set the gameboard. And it wasn’t with an IPA and a brown ale, but with a juniper red ale, a Bronze Age braggot, and meadowsweet mead—beverages you’d be hard pressed to even find at breweries in the States today.

Drinking at Labietis is like traveling back in time, but it’s also a glimpse into the future—one that isn’t dominated by trademarked names of hops, but by what we see, smell, and taste around us.

Even more impressively, Pļaviņš and Melnis never wavered. And they don’t plan to.

“We’re never going to be a hyped brewery with beer nerds knocking at the brewery door,” says Pļaviņš. “We are on a totally different path.”

If you’re ever in Latvia, we encourage you to follow it.