Shop

For the Sake of the Grain

I’m walking towards a grey door lit by a single weathered streetlight at 3:15 a.m. on a Friday in mid May. Stepping inside, the fluorescent lights sting my eyes while alternative rock roars in my ears. Water sprays from an open valve next to a tangle of hoses. Standing in the middle of the organized chaos is a man in a black long-sleeve shirt, brown boots, and tan cargo overalls. A pair of black gloves with “Nick” written on the grey cuff sprouts from his back pocket.

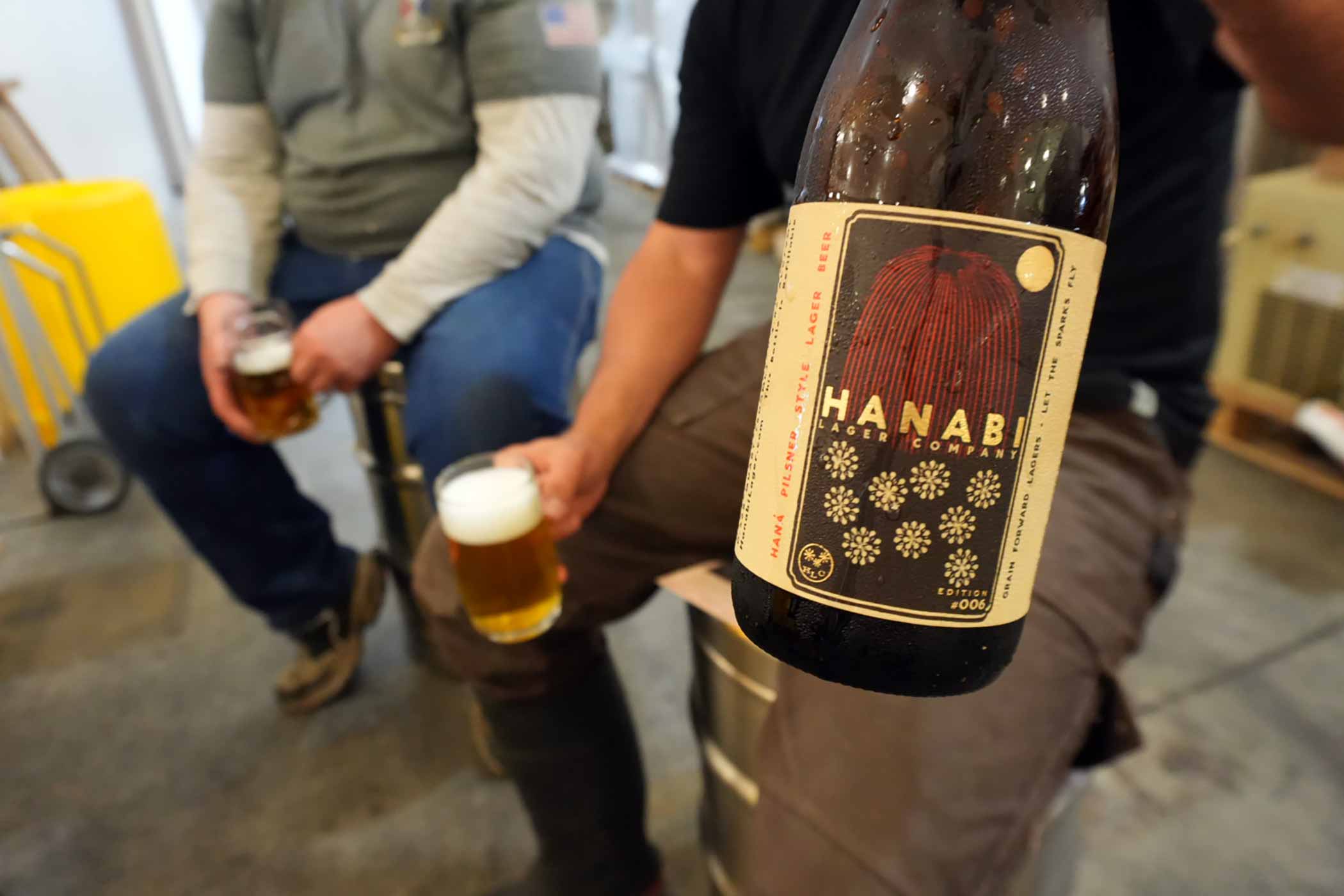

Nick Gislason, co-founder of Hanabi Lager in Napa, California, hands me a pair of earplugs, his smile drawing a full line between his furry mutton chops. We’re about to mash in for a triple-decocted lager brewed with a rare, almost unattainable grain called San Juan Bere.

I’m joining Nick and his motley crew for the second day of their arduous brewing season, a three- to four-day stint of sixteen-hour-plus brew days conducted only four times a year. Each is uniquely engineered around one specific, often hard-to-source heritage grain.

Nick bounces away to check a temperature gauge, and I think to myself, what have I gotten myself into?

From Fireworks to Fermentation

Photography courtesy of Suzanne Becker Bronk

As a child growing up in the San Juan Islands, Nick was obsessed with fireworks, and wanted to make his own. His parents told him if he apprenticed under a professional for a couple years, he could build a workshop. Nick started apprenticing with Dwight Walters (who ran the local fireworks show), catching the 6 a.m. ferry to Lopez Island to make fireworks all day. Before catching the boat home, he’d hang out at Dwight’s house.

“That was how two things entered my life,” says the current head winemaker at Screaming Eagle and Hanabi Lager co-founder. “One was wine, and the other was Japanese-style Hanabi.”

As Nick tells it, Dwight had quite a stash of wines. While waiting for the ferry, Dwight, a former geologist, gave Nick little sips, educating him about soil types and terroir.

“That lit the spark,” says Nick, who also read books from Dwight’s library, discovering an old seventeenth-century Japanese firework catalog. “You didn’t have photography in those days, so you would paint what the fireworks looked like. Those images burned into my mind and stuck with me,” says Nick as he hands me a postcard of Hanabi Lager’s latest Spring 2024 release.

On a tan background, a black box sports bursts of teal and red. Along the left-hand seam, the words “Steffi Pilsner Style Lager Beer – #23” and on the right, “Brewed for New Beginnings – Let the Sparks Fly.”

The #23 refers to a page of a centuries-old fireworks catalog. The beer’s name, “Steffi Pilsner Style Lager Beer,” references the feature grain.

I find several other cards strewn throughout the brewery, with names and numbers like Feldblume – #98, Isaria – #97, and Purple Egyptian – #67 (one of Nick’s favorites).

When Nick started Hanabi Lager, he chose the name purposefully. He says hana means flowers in Japanese, and bi means fire. “So it’s flowers of fire, which is the mentality of how Japanese culture looks at fireworks,” he says. “It’s this art form meant to emulate nature, so the fireworks are named after different flowers, trees, and weather patterns. Some symbolize life cycles—being young, growing up, getting old, and finally, finishing.”

Which is precisely how Nick approaches his grain-forward brewing at Hanabi Lager.

Grain First

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

At exactly 4:20 a.m., a few men lift a one-hundred-plus-pound Brite barrel of floor-malted, milled San Juan Bere grain. Tossing the malt into a small, square basin, they begin an almost meditative ritual. Jared McClintock pulls a lever, and metal on metal clangs repeatedly as hot water fills the basin.

While hot to a human hand, it’s much cooler than the 150° F water typically used when mashing in. As we watch, Nick explains that tougher, older grain varieties like San Juan Bere need extra time to gently soak up slightly cooler water; otherwise, you risk denaturing and killing the enzymes.

“I’m pretty sure we’re the only brewery that mashes in like this,” Jared says, letting the milled kernels sift through his fingers before vigorously massaging them toward the bottom.

When he’s ready, Jared shouts to Trevor Luttrell, a master welder with a patch of grey scruff on his chin. Trevor pushes a button, triggering the grain suction through a bright green hose into the mash tun.

The process repeats for nine more Brite barrels, taking around forty minutes.

The more time I spend at Hanabi Lager, the more apparent it becomes: Grain always comes first. Over about ten years, Nick and his motley crew have made sixteen beers with fourteen unique grains. Whereas most breweries focus on hops, at Hanabi Lager, grain is the rock star.

Nick talks about the raw materials like putting together a band—the hops are the backup vocals or the bass, “there for support and richness of sound and complexity, but you don’t want them to dominate,” he says. In contrast, the grains are the lead singer.

Throughout fourteen years as Screaming Eagle’s assistant winemaker, Nick touched and felt the grapes, all day, tasting the terroir. He finally asked himself, “Wow, wouldn’t it be cool to do that with grain?”

That’s the goal at Hanabi Lager: to find rare, exclusive heritage or landrace grains and, with the utmost respect, bring them to life within the backdrop of a crisp, clean lager.

“He lets the malt speak for itself,” says Ian Ward, former president of BSG and current CEO of Aroma Sciences, who first introduced Nick to uncommon grains like Chevallier and Haná. “He respects the grains, where they come from, and the role they’ve had in brewing.”

As the hose sucks the final Brite barrel of San Juan Bere over to the mash tun, a shrill whistle sounds, signifying a step of the brew day accomplished. An avid mountain bike rider, Jared tells me these whistles remind him of the bell on his bike, which he rings every time he makes it up a hill or navigates a tricky, rocky path. “I’m giving myself a high five!” he says.

My ears ringing, Nick turns to me. “That’s the last of this grain that exists,” he says, fanning out his hands, mimicking a cut-off point. “After today, there is no more!”

Nick’s almost impossible-to-believe story behind this grain is one of the reasons I knew I needed to wake up at 3 a.m. to be here. The journey of San Juan Bere, a centuries-old grain previously only found in the Orkney area of Scotland, is something of a jaw-dropping, almost cosmic coincidence.

Chasing Seeds

Hanabi Lager Co-Founder Nick Gislason (on the left) and Palouse Heritage Co-Founder Don Scheuerman (on the right) | Photography courtesy of Palouse Heritage

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Years ago, Nick phoned a Midwest seed bank, trying to track down a grain he’d fallen in love with called Scots Bere.

The seed bank only had a handful of seeds, so they suggested Nick connect with their supplier out west. That person only had half a kilo, but he told Nick to call Ghetto Yogi (no joke, that’s his name), who had two kilos, which he offered to sell Nick. Nick agreed but felt like a larger quantity of this elusive Scots Bere remained just out of reach. One Friday night, he started Googling.

“A PDF file pops up for a grain festival in the Palouse area of Washington,” he says. “Just a file floating around on the internet that had this variety, Bere,” and the name of Palouse Heritage Co-Founder Don Scheuerman.

Considering himself a grain gardener, Don and his brother traveled the world, pocketing seeds they believed they could cultivate for a burgeoning craft beer market. Those like Scot’s Bere, “the grain that gave beer its name,” jokes Don. Prominent on the Orkney Islands for brewing beer for around 6,000 years, Scots Bere had been whittled down to only fifty acres in the entire world by the time Don discovered it in 2006. He made it his mission to grow Scots Bere and keep it alive.

At 5 a.m. on a Sunday, Nick and Don got on the phone, connecting instantly and deeply. At noon, they were still talking.

“We were on two parallel adventures that intersected totally serendipitously,” Don tells me with a laugh, assuring Nick that he could get him some sprouted Bere by the next week.

And then Nick says Don told him, “I’ve got another story up my sleeve.”

Because Bere is originally from a maritime climate, a couple of years ago, Don sent a friend to find a place to plant Bere closer to the coast.

This friend visited Olympia, and then the Skagit Valley, but no one wanted to farm an ancient landrace grain. Then, he noticed a ferry landing. He debarked on Lopez Island first, but the stars didn’t align. Next stop west? The San Juan Islands.

At the local watering hole, Herb’s Tavern, he started talking to some local farmers about this 6,000-year-old grain variety he had in his camper parked out front.

The farmers helped him find a spot to plant the grain about three miles from the house Nick’s family built.

“It was the most beautiful crop of Bere that Don had ever seen,” says Nick. “Plump kernels, these big, beautiful grain heads; they were just going nuts!”

As Don wrapped up, he told Nick, “We just harvested that grain, and I have two tons in my barn. They’re all yours if you want them.”

If Hanabi is about brewing all-grain beers with a sense of place, it doesn’t get much closer to home for Nick than working with San Juan Bere.

When Don sent him the first pilot maltings, Nick says he pried the top off these 2,000-pound totes and just stuck his head in them, taking a deep breath. “Fuck, that smells like home,” says the kid who spent summers outside baling hay, making fireworks, and homebrewing. “I never dreamed I’d be brewing with ingredients grown two to three miles from the home I grew up in.”

Lager Life

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

The plan today is to brew a double batch of lager.

“We triple decoct one and single decoct the other, which gives us a range of flavors, and then we combine them in the fermenter,” Jared explains.

With a measuring tape stuck into the QT (quarter-tun mash kettle), Jared and Nick watch closely as the tank fills. Once it’s full, Jared sits on the steps beside the QT, one eye on his watch, the other on a digital thermometer. Every fifteen seconds, his hand stretches across to a knob, moving it half a degree.

He explains that he’s slowly feeding steam into the jacketed kettle, raising the temperature.

“We’re all manual,” he says proudly. “It’s unique as hell.”

With most brewing systems, he says you just set the temperature via a controller click and walk away.

Waving his hand almost like a conductor, Nick mimes that it’s a rhythm, saying, “Sometimes we’re all guns blazing, but like a good album, there are different tempos.”

Along with the blaring, sometimes metal, sometimes nineties hip-hop music, we’re constantly assaulted by the steampunk sounds of a handmade brewery. Metal clangs, valves squeak, steam hisses, hoses sploosh. Over the years, Nick, Jared, and Trevor have built this little breathing beast together, welding each piece at Screaming Eagle during marathon-long weekends.

Jared used to manage operations at JV Northwest, the country’s premier brewery equipment manufacturer, which has built kits for everyone from Wayfinder to Deschutes. Trevor was one of Jared’s best welders. They met Nick when he came up one weekend to, you know, just weld for fun, another hobby he picked up as a kid.

“A lot of people just buy stuff,” says Trevor.” You can buy anything with money. We build it.”

A whistle blows, jolting Trevor from his reverie. Jared just signaled that our single decoction has reached temp. After a flurry of activity to separate and manage the decoction and step mashes and then transfer to the lauter tun, we’re on cruise control for the next six hours as liquid dribbles between vessels. Jared stays chained to the brew deck, moving in a triangle between the lauter tun on his left, the QT in front of him, and the boil kettle to his right. Sometimes, he turns a small wheel millimeters in one direction. The valve (which he thinks could have had another life in some school basement boiler) controls the flow of steam, making things hotter or cooler to keep the wort at a vigorous boil.

“Most breweries just set the controller at 212,” he says. “But for us, this is my throttle.”

Reading the Trub Leaves

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

Photography courtesy of Grace Lee-Weitz | Hop Culture

By noon, I’ve worked the equivalent of a full-day desk job without sitting down once, and I’m dreaming of that end-of-shift pint. I have a fine layer of grain dust all over my brown cargo pants from stepping outside to help mill grain for the next day. Lifting a pallet of fifty-five-pound grain bags has left my quads dragging.

Up on the brew deck, it’s one of Jared’s favorite parts of the day. The rest of the wort has siphoned out of the boil kettle, leaving behind a macaroon-domed trub pile with cracks and crevices. He calls it reading the trub leaves.

This one looks like a Pi symbol. We agree it’s a full circle moment—something to do with Nick and San Juan Bere—but admittedly, our brains are slogging a bit. A couple hours later, I finally see the trub from the second batch poke through like the colors of the sunrise, with rings of green, yellow, orange, red, and brown.

Finally, at 3:52 p.m., a low ship horn blubbers, a ship pulling into port. Jared walks out with six bottles.

The gang pulls a series of overturned buckets and empty kegs into a circle just outside the brewhouse. When Nick crunches down on his flipped yellow bucket, it’s the first time I’ve seen him sit all day. Although his feet are finally still, his mind keeps racing.

“We hit the Platos pretty good. We came in point-two off target. I’m happy with that,” Nick says demurely, nodding around the circle as we cheers. “Pretty good brew.”

At 5:54 p.m., I walk out into twinkling sunlight. Letting the door close behind me, I savor the silence. Like the last fading grand finale fireworks, lines of smoke and color slowly disappear behind me. But a few invisible things remain. My ears still ringing, my eyes still blinking; I’m awed as I amble back to my car. I head home with dreams of sleeping in tomorrow.

Nick, Jared, and Trevor will head home, shower, change, wind down, and go to bed early. Because at 2:15 a.m., they’ll wake up and do it all over again.

This is the way at Hanabi Lager. For the sake of the grain.