Shop

Schlenkerla: The Historic Smoked Beer Brewery

Top Stories:

When historians discuss smoked beers, or rauchbiers, one brewery stands the test of time—Schlenkerla, the quintessential smoked beer brewery. With a rich history dating back to the early 1400s, Bamberg’s iconic brewery has a past that’s, well, a little smoky.

Today, most people believe that Schlenkerla invented the smoked beer by accident. The story goes that, when the brewery burned down, a brewer decided to share the charred product with the town instead of dumping it. “It always sounded weird to me because, when your brewery burns down, and you have a burned product, I don’t think you would sell that,” says Matthias Trum, the sixth-generation brewer at Bamberg’s “Heller-Bräu” Trum, more commonly known as Schlenkerla.

Trum, who emphasizes this is a myth, probably knows better than anyone. He grew up in a flat above the tavern.

“I didn’t have a key to the house,” says Trum. “The door was always open. … The whole thing was pretty much my home.”

As a kid, when he bathed, he could hear the goings on in the tavern’s kitchen below. And when he wanted to have fun, Trum climbed amongst the grain silos in the brewery. At five years old, Trum started voluntarily working in the kitchen, “peeling potatoes to get some additional allowance,” he explains.

When he turned the legal drinking age (sixteen in Germany), his room was always the meeting point. “We didn’t have mobile phones at the time, but it wasn’t necessary,” says Trum, because everyone knew to show up at his room on Friday night. “It was a cool thing to come from the brewery.”

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

On a September morning (evening for Trum), he Zoomed with us from his old childhood bedroom, now his office. Behind him, portraits of his entire family line.

Trum seemed almost destined to brew. And he has not taken that legacy lightly.

“In German, you say top von decke, so a pot and a lid, they fit together. And for me, it was exactly that,” says Trum, who cut his teeth at the world’s oldest brewery, Weihenstephan, before returning to Schlenkerla. “Schlenkerla was perfect for me. And I hope I’m adequately good enough for Schlenkerla.”

He seems almost offended by the myth of burned beer that tour guides often tell outside the window of his tavern office.

Although unproven, the story spread like wildfire.

But as Trum shares with us, history suggests a different tale.

So, when the smoke cleared, who created the first smoked beer? Perhaps, as Trum told us, we’re actually asking the wrong question.

The History of Smoked Beer…and the Smokeless Kiln

Schlenkerla sixth-generation brewer Matthias Trum | Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

“The interesting question is not who invented smoked beer,” Trum says wryly. “The interesting question is who invented non-smoked beer?”

For a majority of beer’s history, all beers were smoked beers.

“When you look at how the ancient civilizations made beer, they probably kilned the malt just out in the open sun,” comments Trum, who has spent years researching smoked beer, finding the oldest fire kilns from the Bronze Age, about 5,000 years ago in today’s Jordan, close to the Dead Sea.

However, a moist climate in Central Europe and Bavaria made it impractical to dry malt outdoors. Drying over an open fire would have been preferred.

“Two hundred years ago, beers were named winter beer, summer beer, or lager beer. There was no term for smoked beer,” Trum explains. “All the beers were smoky.”

But in 1635, Cornwall’s Sir Nicholas Halse developed the “smokeless” kiln. Bypassing wood as a fuel source, the invention made it easier and faster to kiln malt.

When Halse received a patent for the non-smoke kiln on July 23, 1635, smoked beer immediately started to disappear. Trum says it took less than a century for breweries to stop using smoke kilns in England. By around 1800, German breweries had adopted the new technology, too.

“The first one to dismantle the Bavarian kiln, meaning smoke kiln, was the Spaten Brewery in Munich, run by Gabriel Sedlmayr, the elder,” Trum explains. “He replaced it with…as they called it, the English kiln. So even in Germany, the modern-type kiln had the name England in it, because it was so synonymous with that invention of Sir Nicholas Halse.”

By the turn of the twentieth century, only four breweries still used smoked malt, and today, Schlenkerla and one other Bamberg brewery, Spezial, remain the only producers of traditional smoked beer.

If the rest of the country gave up on smoked beer, why didn’t Bamberg?

Where There’s Smoke, There’s Firewood

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

According to Occam’s Razor, the simplest explanation is usually right.

To the west of Bamberg lies Germany’s largest Beechwood forest. A core component of rauchbier, Beechwood isn’t found everywhere.

In a rural area of Northern Bavaria, Bamberg had the easiest access to one of smoked beer’s main ingredients.

Moreover, Bamberg’s strict religious association affected the town.

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

Trum explains that until 1804, the church ran Bamberg. “Like the state of the Vatican in Rome,” he says. “That setup, of course, helps conserve traditions or prevents the introduction of modern things.”

During the 1900s, a typical day in Bamberg consisted of two things: church and beer.

An old city council member elaborates in a news article that Trum tracked down from 1898. “He said, we start very early in the morning with morning Mass and prayer. After that, we go to our favorite tavern, which in our case is Schlenkerla,” says Trum. “We have our morning pint, and then we go for a walk, and then we go to the beer garden, have another beer there, and in the evening, we come back to Schlenkerla, to the Stammtisch (which translates to ‘the regulars’ table’). Every day, the same itinerary.”

Perhaps a touch stubborn and conservative, Bamberg simply refused to modernize—content with smoked beer.

And Schlenkerla is content to preserve it.

Fire Walk with Me: The Legend of Schlenkerla

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

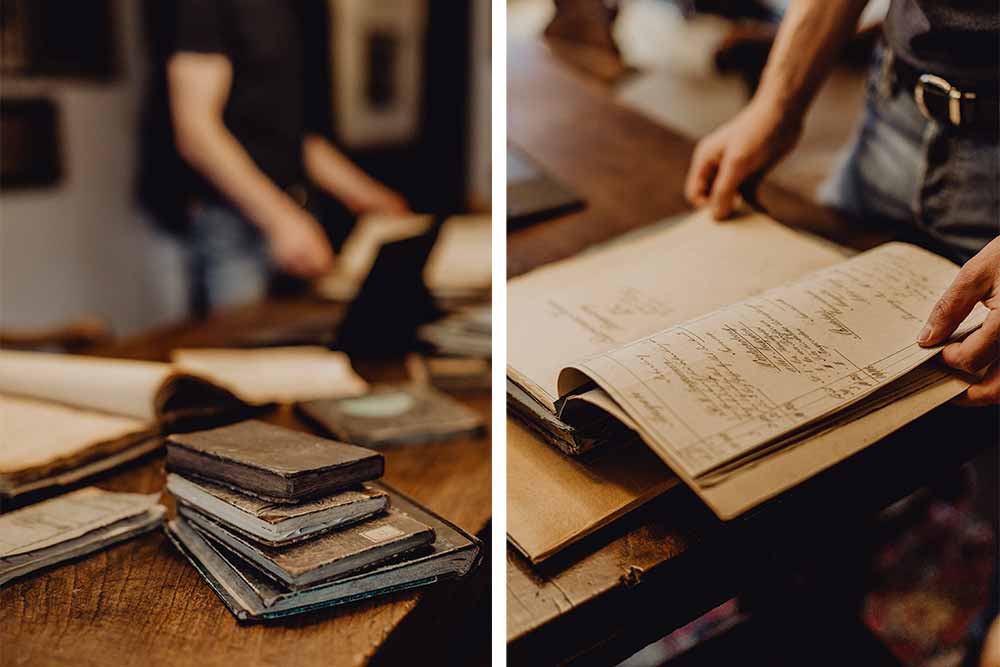

While the exact history of Schlenkerla is a bit foggy, Trum says he’s found breadcrumbs—notably a historical reference from 1387. “A historian found a document for us that doesn’t say anything about beer making, but … rock cellars, and that a brewer owned [the building],” says Trum. “I think this is a certain clue.” The earliest official record of the brewery dates back to 1405, then known as the House of the Blue Lion and later changed to Heller-Bräu when Johann Wolfgang Heller took over as the owner in the eighteenth century.

According to Schlenkerla’s own documentation, Andreas Graser took ownership in 1875, passing everything to his son Michael Graser in 1907. By 1960, Michael’s daughter, Elisabeth Graser, and her husband, Jakob Trum, took over.

Although the company register still keeps “Heller-Bräu” Trum as the name today, most know the brewery by a different name—Schlenkerla.

And the story of that name? Well, it’s not just a walk in the park.

In the late 1800s, after an accident, previous-owner Andreas walked with his arms dangling and swinging, a gait known as schlenkern in German. Since Andreas had a reputation for being a grumpy stickler in the tavern, patrons likely coined the nickname schlenkerla in jest.

“Andreas made a perfect target for such a fun name like the Little Dangler,” explains Trum.

When Andreas’ son, Michael, took over, he boldly adopted the name Schlenkerla. Trum told us that he even trademarked the nickname to immortalize and preserve his father’s infamy.

Trum considers Michael among the most influential people in the brewery’s history. And not just for its name.

“He preserved the old way of doing smoke,” says Trum. “He very much laid the basis for what Schlenkerla is today in the early twentieth century. And every generation after him is trying to follow his lead and to continue preserving what he has started.”

So What Exactly Is Rauchbier? And How Does Schlenkerla Make Their Famous One?

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

Rauchbier, which literally translates to “smoked beer” in German, can be a bit polarizing. That said, those open to trying it are rewarded.

“There’s an old Bamberg proverb that, when you drink smoked beer, … you have to drink three pints to fully appreciate the aroma and flavor,” says Trum. “And, of course, after three pints, you can make your way back to the hotel in a ‘schlenkerla-ish’ or the Schlenkerla way!”

Arguably the most classic example of the style, Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier – Märzen is a dark, aromatic, bottom-fermented 5.1% ABV lager—essentially a smoked Märzen—brewed with Original Schlenkerla Smokemalt and tapped according to the old tradition directly from the gravity-fed oakwood cask in the fourteenth-century brewery tavern.

It all starts with the steeping process. “We have a stainless steel basin in which the grain, the barley, is put inside,” explains Trum. “It soaks in the water for roughly a day intermittently with air so that the grain doesn’t suffocate.”

Afterward, the grain spends roughly a week in germination boxes.

The secret of Schlenkerla’s smoked beer lies in the next step—the kilning process.

For twenty-four hours, the brewery places grain into a closed kiln with an open fireplace underneath. As the malt dries, the smoke from the Beechwood logs infuses flavor.

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

“The classic Märzen smoke beer is made with (basically) 100 percent smoked malt and a tiny bit of roast malt to fill out the color differences between malt batches,” says Trum, “because obviously with an open fire, you cannot adjust the color as exactly as in a modern kiln.”

Other styles brewed by Schlenkerla, like the Urbock, Eiche – Doppelbock, Fastenbier – Lentbeer, Weizen, Erle – Schwarziber (black lager), and Weicshel – Rotbier (red lager), have anywhere from fifty to one-hundred percent smoked malt—usually using Beechwood, but sometimes other types of wood like oak as well.

While brewing, Schlenkerla uses a decoction mash to emphasize the malt’s unique notes. “By boiling the mash, you add additional flavors, and you get a more intense and more bread-like aroma in the beer,” explains Trum.

Brewing Schlenkerla’s classic Märzen takes approximately eight hours, meaning they can only produce three batches daily. Trum says that he has fully automated the brew house to improve efficiency. However, he notes that the mash tun and lauter tun are still made of classic copper and configured using natural gravity to help transfer the wort.

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

After fermentation, the rauchbier matures in stainless steel lagering vessels (wooden barrels back in the day!) in the rock cellars.

The classic Märzen smoked beer lagers for two months, which is relatively lengthy. Beginning at a natural cave temperature of eight degrees Celsius, Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier ends at approximately one degree Celsius for optimal turbidity clearance and protein stability, as Trum prefers to avoid filters. Additionally, the lagering time allows the beer to fully develop in flavor.

With the brewing out of the way, let’s send up a smoke signal and grab a pint.

What Does Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier Taste Like?

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

“The first sip is intense, layered, and there’s a lot to ponder and think about when drinking it,” says Hop Culture Contributor Ryan Pachmayer, who traveled to Bavaria last year and put together this handy guide for us on the Franconia region. “It’s rich, toasty, meaty, subtly sweet, and, of course, smoky—kind of like a toasty campfire caramel cookie.” As the beer changes with temperature, new flavors arise, with some even saying this beer tastes like savory, smoked bacon.

As far as freshness versus aging, Trum has “two hearts in my chest,” he explains. As a German brewmaster, Trum’s ultimate goal for the final beer is to keep the flavor components in balance. Smoke is an additional flavor component of Schlenkerla beers. When beer ages, the maltiness decreases over time, making it seem like the smokiness increases. “Our brain tricks us,” says Trum. “Of course, I can live with [that]!”

In fact, one of Trum’s uncles, who lives in Switzerland, prefers it. He comes to Bamberg once a year, filling up the trunk of his car with smoked beers. ”He told me he always drinks the one-year-old beer because he wants more smoked flavor!” says Trum.

Long story short, not everybody enjoys smoked beer in the same way, and that’s just fine.

But at least once in your life, you should enjoy Schlenkerla’s rauchbier right from the source.

Where Should You Drink Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier?

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

Trum advocates that, when you come to Bamberg and want to drink smoked beer, you should go to the source and have it from the wooden barrel, which emanates a distinct flavor compared to the bottles.

“The carbonation in the wooden barrel is a little bit lower, and it’s more mellow in that flavor. It’s the freshest you can have,” he says. “And the smokiness from the wooden barrel actually is a little bit less because of all the freshness and the lower acidity.”

Trum says many people have told him they don’t enjoy Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier when they first try it from the bottle. “Once they had it from the wooden barrel, they said, ‘Oh! This is much better,’” explains Trum. “Those people out there who don’t like smoked beer, you should try it from the wooden barrel. If you still don’t like it, okay, it’s not your thing, but give it a chance.”

As for the tavern itself, Schlenkerla has two distinct atmospheres. Inside, you can sip your beer surrounded by history, while outside, you can drink among the hustle and bustle of the town.

On the weekends and evenings, Trum says the street outside the Tavern is packed like a festival.

“You stand there; you wait for people to pass by. Oh, I haven’t seen you for a long time. Come on, join me for a beer,” illustrates Trum. “It’s like a community gathering of the locals fed by smoked beer.”

At Schlenkerla, History Repeats Itself

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

Who doesn’t love to make history? Fortunately for us, that’s Trum’s specialty.

Today, Schlenkerla thrives under Trum’s guidance, focusing on centuries-old traditions with an eye half-open to the future. Something he picked up while at Weihenstephan, where he learned not only modern brewing techniques but also historic ones.

So, while the Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier is the most celebrated, it’s by no means the only beer they make.

When dreaming up potential ideas, Trum walks the tightrope between preserving history and keeping things fresh. That is the cornerstone of modern-day Schlenkerla.

In the 1990s, Trum’s father introduced the smoked Weizen, a wheat beer, because, as Trum explains, “there was a lot of demand for wheat beers at the time.”

“Of course, preserving the old smoky traditions is what Schlenkerla is about,” Trum says. “[But] in such an old place, you can do new things.”

For instance, the Eiche – Doppelbock features malt kilned with oak instead of Beechwood. “I found all these English texts where oak was the preferred wood for drying malt and also for drying hops,” Trum says.

Or Fastenbier – Lentbeer, an unfiltered smoked beer that Trum introduced in 2005. Inspired by the beers monks historically drank while fasting during Lent, Fastenbier represents nourishment. “There’s a Latin proverb which says liquida non francundium, the liquids don’t break the fast,” says Trum. “The special thing about the Fastenbier is it’s unfiltered with the nourishing yeast inside.”

Last year, Schlenkerla introduced two more beers along that line, including the cherry smoked red lager, known as the Weichsel, the German word for the sour cherry tree.

Another recent addition, a 4.2% ABV black lager inspired by the traditional Czech dark lagers, uses Alder wood-fired kiln malt. Trum again found an old text stating Alder is a very suitable wood for making malt because it burns for a long time.

“Basically, I take historic beer styles and try to deduce from historic sources what the key elements were and possibly also what the flavor might have been like,” explains Trum. “Then together, with my head brewmaster, we develop a strategy on how we can [brew it] with modern raw materials and brewing equipment.”

Trum indicates he’s not stopping. “I have more ideas for the future,” he says excitedly, noting he might even venture outside of smoked beers. “But that’s an entirely different story!”

What Is the Future of Schlenkerla?

Photography courtesy of Schlenkerla

While there is no explicit expectation, Trum does hope one of his children will take the reins one day. We have to admit that we would enjoy seeing the brewery passed down and the traditions preserved.

With smoked beer overcoming the odds, we would love nothing more than to witness Schlenkerla thriving for generations to come.

A few things have changed at Schlenkerla. For instance, they now ship beer on trucks instead of horse carriers.

But so much remains the same.

”When you sit on a chair which has been around for 100 years, the table 150 years, and the room around you is 500 years old,” Trum emphasizes, and drink an Aecht Schlenkerla Rauchbier right from the wooden barrel, well, that will never get old.