Shop

What Is Mead? The Buzz Behind the World’s Oldest Fermented Beverage

Like This, Read That

What is the world’s oldest fermented beverage? Beer? Wine? The answer may surprise you. Although if you even semi-paid attention to the title of this piece, you already have the answer. Made by fermenting honey, water, and sometimes fruit or spices, mead’s story stretches back over nine thousand years, making it the true OG of alcohol.

But don’t picture just Vikings guzzling from horns or Renaissance fair-goers clinking goblets. While those images aren’t entirely wrong, they barely scratch the surface of what mead really is. This honey-based drink has been woven into countless cultures across the globe, from ancient China to Mayan temples to Celtic mythology. And today, a new wave of innovative meaderies is redefining it for modern palates.

These makers are pulling from centuries of tradition while experimenting with bold flavors, fresh ingredients, and creative techniques. Much like bees spreading pollen, they’re carrying mead into the future—one glass at a time.

And with meads ranking among the highest-rated beverages on Untappd, it begs the question: What exactly is all the buzz about?

Why Do We Call Mead the Oldest Fermented Beverage?

Evidence!

Archaeologists in Jiahu, a Neolithic village in China, unearthed pottery shards that, when chemically analyzed, showed remnants of a fermented beverage made with rice, honey, grapes, and hawthorn berries.

Dating somewhere between 7000 and 6600 BCE, these jars are notable because they predate the oldest evidence of wine in the Middle East by more than 500 years.

The study, led by Dr. Patrick McGovern from the University of Pennsylvania’s Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Dr. Juzhong Zhang from the University of Science and Technology of China, and many more, analyzed nine-thousand-year-old pores. The discovery remains one of the most influential because it showed the first hard evidence of fermented beverages in ancient Chinese culture, remapping our understanding of the world’s oldest fermented beverages.

Despite early evidence in China, mead shows up in quite a few cultures, reaching across continents, countries, and centuries.

“What’s really cool is no matter who you are and no matter what your background is, your ancestors were drinking mead,” says Jeff Herbert, Co-Founder of Superstition Meadery in Prescott, AZ. “So no matter who you are, your ancestors, my ancestors, they were drinking mead.”

Off the top of his head, Herbert mentions finding mead across Africa, India, Mayan culture, Celtic mythology, with Vikings, and in Europe, where it is still Poland’s national beverage.

Zymarium Meadery Co-Founder Joe Leigh says, if you think about it, the history of mead makes sense. “Bees were making honey long before we were planting grains or grapes,” he explains. “[Mead] probably predates the wheel.”

He adds, “Hunters and gatherers would come across honey and that was literally liquid gold to them, the most magical thing ever.”

After collecting the honey, Leigh says they probably didn’t have a way to keep the moisture out, so it would just ferment on its own.

“Mead is definitely the original alcohol,” he says matter-of-factly.

Herbert agrees, noting mead used to be considered the “drink of the gods,” thanks to its precious nature.

Historically, cultures held this fermented honey beverage in such high regard that they would gift a month (or moon’s cycle) supply to newlywed couples to break down barriers to help start a family. Hence, the word: honeymoon.

“That’s why mead is known as the original aphrodisiac,” laughs Herbert, who admits that when his friends get married and send him an email with a registry full of toasters and ovens, he often counters, “No, you’re getting mead!”

So What Exactly Is Mead, Then?

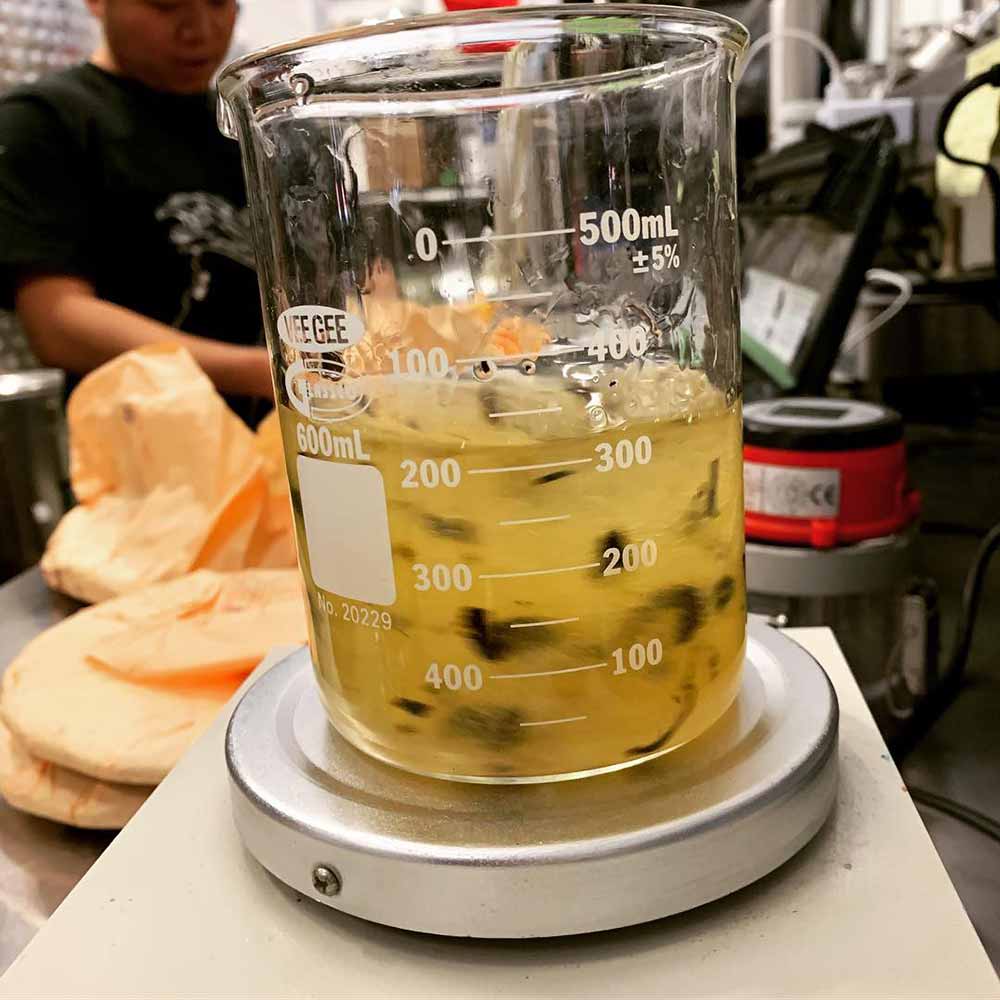

Photography courtesy of Zymarium Meadery

Leigh explains it best, “grapes make wine, grain makes beer, and honey makes mead.”

Both Leigh and Herbert, and Illinois-based Standard Meadery Owner and Head Mead Maker Adam Lynch tell us that they answer this very question at their meadery every single day. Ninety percent of the people who walk into Superstition’s taproom, according to Herbert, ask, “Hey, what’s mead?”

“Constant education” is the way Lynch describes it.

In its thirteen-year history, Superstition has released over five hundred meads, so Herbert has the answer down pat, and it’s similar to Leigh’s.

“When you ferment wine, you ferment grapes; when you make cider, you use apples; when you make beer, you use grain and hops,” he says. “We use honey.”

Inside the Hive Mind

Photography courtesy of Drew Garraway

Without a doubt, honey is the most important ingredient in mead. This sweet nectar is the DNA of M-E-A-D.

But not all honeys are the same!

The sweet sludge we buy at the grocery store is ultra-filtered and pasteurized. “Everything has been removed, so it’ll never crystallize and stays liquid,” explains Leigh, noting all the pollen has been stripped so it’s just been “blended to the flavor of gray.”

He calls it more like sugar syrup at that point. “Everything that makes the honey special has been removed,” he says.

When you get unfiltered, unheated honey in big fifty-gallon drums that each weigh 650 pounds from local pollinators, like they do at Zymarium, you’re getting the purest expression of a varietal.

“Having fresh honey is phenomenal,” says Leigh. “The aroma when you open up the drum … smells like spring.”

And the flavor changes depending on the country, region, area, etc. Much like grapes have terroir, affected by the weather, soil conditions, and temperature, honey also takes on the tastes of the land and changes seasonally.

Superstition primarily uses an Arizona wildflower honey and Arizona mesquite honey, sourcing specific varietals for special projects or one-offs.

For instance, for Superstition’s nine-year anniversary, Herbert sourced nine different honeys from five different beekeepers.

At Standard Meadery, Lynch says they purchase honey through smaller apiaries or brokers who go all over the world to find interesting honey. He says they use orange blossom the most, following its harvest from Florida and California to Mexico and South America.

Honey is a raw agricultural product, so you aren’t only getting different flavors based on geography but based on all the conditions around it.

“Even if we sought to get the exact same honey every single year,” says Zymarium Meadery’s other Co-Founder, Ginger Leigh, “it’s impossible because it changes yearly.”

You can see the wide spectrum of honey in Zymarium’s first batch of Existential Magnetism, a mead featuring Florida’s Black Mangrove honey. And a second batch, which highlighted Lehua Blossom Honey from Hawaii.

The former fermented with bright pineapple notes, to which Leigh added one hundred pounds of raw coconut. Although the honey initially expressed butterscotch caramel, “fermentation changes it in a really novel way,” says Leigh. “It would have been a crime not to put it on coconut.”

The latter expressed overripe pineapple, butterscotch, and “this tropical fruit explosion,” says Leigh, who calls this the most unique honey he’s ever had. “I love sharing it with people because the look on their faces is like: I didn’t know honey could taste like this.”

With these meads, Zymarium lets the honey tell its own story.

From Hive to Home

Photography courtesy of Superstition Meadery

At its simplest form, mead is just honey mixed with water, pitched with yeast.

“Imagine a five-gallon container,” explains Herbert. “If you had one gallon of honey and four gallons of water and you mix that up, that would be a traditional mead.”

At Zymarium, Leigh says they don’t use any heat to “protect all those delicate aromatics and keep the honey as pristine as possible through fermentation.”

If mixing water with grain during beermaking leads to wort, then mixing water with honey creates must. “As soon as you add yeast and start to ferment,” says Herbert, “now you have the beginning of what will become mead.”

For yeast strains, Zymarium sticks mainly to wine varieties—a white version if making a more traditional mead and a red one if adding fruit like berries.

Herbert likes to follow a color code: lighter-colored meads (without dark-rich fruits) use a white wine yeast, while darker fruits or grapes need a red wine yeast.

At Standard Meadery, Lynch sticks to champagne or wine yeasts—like 71B and QA23—because he’s looking for a really hardy yeast that can handle his mead’s higher gravity and lower pH levels. “A lot of the time we need really strong strains of yeast to survive and finish fermentation,” he explains.

While Leigh says you can use beer yeast, they’ve gotten better results with wine strains because the chemistry is more similar.

“That’s the holy trinity of wine,” Lynch agrees regarding mead fermentation. “Making something that’s stable is a balance between those three things—sugar, alcohol, and acid.”

Photography courtesy of Superstition Meadery

Mead fermentation crosses over with beer, Herbert says, when it comes to carefully monitoring the temperature and pH levels, as yeast will convert the fermentable sugars from the honey into alcohol. Less honey creates a more sessionable mead around 5% to 6% ABV with no residual sugar. Whereas more honey increases residual sugars and alcohol content, which can vary anywhere from 10%–16% ABV and higher.

On average, if Leigh shoots for a 14% ABV dry mead made with a classic white wine yeast strain, he uses three pounds of honey per gallon. To make a sweeter, richer, more decadent mead, he can double the honey to six pounds. “If you cut that in half and use one and a half pounds, you’re going to end up with a 7% ABV mead that’s dry,” he says.

Herbert explains that with a gallon of honey weighing twelve pounds for every pound of honey mixed into five gallons, you’ll get about 1% alcohol by volume if you ferment all the sugar out.

“Yeast is lazy like anything else,” says Leigh. “So it’s going to eat the simplest sugars first.”

Ginger points out that this chemical breakdown has an added benefit: no (or at least less intense) hangovers!

“We’ve had a lot of people tell us that they get a nice smooth buzz,” she says, “and then they wake up the next day and they’re like, I never got a hangover.”

Fruit, Fermentation, and Funk

Photography courtesy of Zymarium Meadery

While honey is the most important, it doesn’t have to be the only ingredient in mead.

Especially in modern meaderies, a literal Eden’s worth of produce has made it into bottles.

Leigh says where you add the fruit depends on the product.

For instance, he prefers not to ferment citrus because it turns into “orange juice that’s gone a little south,” he grimaces. “But berries love to be fermented.”

Zymarium makes a series called Endless Meads, which focuses solely on honey and a specific fruit. Usually, you take honey, dilute it with water, add your fruit, and ferment.

With Zymarium’s Endless Meads, they dilute honey with two thousand pounds of fresh fruit. No water needed here. Just the juice from crushed fruit.

“It is absolutely an insane amount of work,” says Leigh, who has to constantly punch and press the chosen fruit down to extract the needed liquid.

What he gets, though, is an incredible amount of skin and tannins that contribute to color and flavor.

Zymarium has cycled through all types of produce, including berries, bananas, and even pears. The latter two Leigh will then condition on dried bananas or dried pears, respectively, to “keep pushing that fruit profile as far as possible.”

For its higher-end more dessert-style meads, Standard Meadery follows a similar approach, fermenting on whole fruit—skins, stems, seeds, and all. “We try to cram as much fruit and as much honey into every single mead we make and use the least amount of water,” he says, meaning, “you get additional complexity and tannins.”

The answer to where to add fruit, according to Herbert, depends. As does the type of fruit, whether it’s juice, purée, or something else.

But Herbert can definitely say that adding fruit post-fermentation allows you to dial in the flavor perfectly. Much like adding hops post-boil through the whirlpool will extract the most amount of flavor and aroma without the bitterness, adding fruit to backsweeten gives the meadmaker more control over the final flavor.

Herbert hedges a bit here, though. “It’s more noble and traditional to put fruit in the beginning and to ferment it with your honey to just see what happens at the end and go.”

Taking the Sting Out of Mead Myths

Photography courtesy of Zymarium Meadery

Don’t be hoodwinked by the honey. Yes, this bee by-product is sweet, but that doesn’t necessarily mean all meads will be sweet.

Much like wines can range in acidity and tannins, meads also fall on a spectrum from bone dry to super sweet.

Herbert breaks mead down into two overarching categories: wine-style mead, which is generally not as bubbly, and session-style meads that have a lower ABV and higher carbonation.

Within those umbrellas, Herbert says mead can fall into a wide variety of styles, including Melomel (fruit mead)—which includes Cyser (apple mead) and Pyment (grape mead)—Metheglin (mead with herbs or spices), Bochet (caramelized honey mead), and Braggot (beer-mead hybrid), to name a few.

Herbert says that dissecting all the categories would be a two-hour conversation, but generally at Superstition, he’ll put higher-ABV, more traditional meads into bottles and lower-ABV meads with bubbles into a can.

Then it’s up to the meadmaker to figure out how to present the mead texturally, which means these categories are a bit subjective, but Herbert breaks them down as follows:

Dry: No sugar left or very little. Beer Judge Certification Program guidelines have these meads with a specific gravity (a measurement of the density of a liquid compared to water, indicating sugar content) of 0.990-1.010.

Off-Dry: When a mead has a perceptible sweetness level and corresponding body, but has not moved into that semi-sweet level.

Semi-Sweet: More perceptible sweetness, but not over the top. BCJP specific gravity = 1.010-1.025.

Sweet: Bigger, bolder sweetness. BCJP specific gravity = 1.025-1.050.

Superstition plays mostly in the semi-sweet sandbox. “It’s a balanced product that looks beautiful, smells great, and tastes great,” says Herbert, “You can taste either the honey or the fruit or the special ingredients because that residual sugar is present, but it’s not too sweet.”

How to Taste, Store, and Age Mead

Photography courtesy of Zymarium Meadery

As a good rule of thumb, Leigh says, “when in doubt, always open up the mead and drink it cold because you can let it warm up as you’re sipping on it.”

At Zymarium’s taproom, they serve mead at three different temperatures—the classic beer range of thirty-eight degrees, “like out of the walk-in,” says Leigh, forty-eight and fifty-eight degrees, “like wine rules,” where red wine can be too cold or white wine can be too warm.

For lower-ABV, more carbonated meads, Herbert recommends drinking those like a beer— “cold, coming right out the cooler.” For something more dry, he also thinks chilled is the way to go, while a barrel-aged 14% ABV mead should be drunk closer to room temperature to maximize all its aromatics and flavor compounds.

But as a baseline, “I like to start chilled,” says Herbert, who recommends leaving a bottle open on the counter as you serve it so that it warms up slowly over time.

Lynch stores his bottled meads like wine, on their side in a cool place, to give the liquid time to come in contact with the cork. Whereas, for his session meads, he says you can just keep those in the fridge.

To taste, Leigh suggests smelling first and sipping a few times. The first sip adjusts your palate, so as you continue to drink and let the mead warm up, the more you can appreciate the flavors.

But really, there isn’t a wrong way to enjoy mead.

“We try to ask people what they’re in the mood for right now,” explains Ginger, as opposed to what they usually drink.

Much like other preferences, what you’re in the mood for can change daily.

“It’s a lot like music,” says Ginger. “I’m not going to listen to the same song all day; it really depends on what I’m doing at the moment.”

Leigh suggests getting one of Zymarium’s flights, which they can curate for you, or you can create one yourself.

If you choose one of their preset flights, Zymarium sets up sips for you from driest to sweetest, most delicate to bold.

Herbert also strongly suggests you try one of Superstition’s flights, which offers twelve sips. Starting with three or four carbonated products with lower ABV, Superstition’s flights work up to sweeter, boozier, more flavorful, and barrel-aged as you get to the end.

For those who want to take their bottles home, according to Leigh, mead doesn’t need to age. “If it is made correctly,” he says, “you can have an incredible mead that doesn’t need years in a closet.”

If you do want to age mead, though, the liquid will improve over the year.

“It’s high sugar, high acid, high alcohol, and sometimes high oak,” says Leigh, noting all those things mean mead improves over at least ten years. “The florals come out even more, and the flavors keep ramping up year after year.”

Even once in a while, Herbert admits he has found 16oz Superstition cans from four years ago in the back of his fridge. “I’ll crack it,” he shares, “and it’s great!”

To preserve the mead, Leigh recommends the wine approach; storing bottles in the fridge is best, but a cool cellar works too.

Leigh does give a slight caveat here. “We’re very careful with our mead,” he says. At every step of the process, Zymarium minimizes oxygen pickup. Much like beer, oxygen, temperature, and light are the enemies of mead degradation.

It’s Not Beer; It’s Not Wine; It’s Mead!

From ancient jars in China to bustling modern taprooms, mead has traveled across continents, cultures, and centuries. Once revered as the “drink of the gods” and gifted to newlyweds during their honeymoon, this fermented honey beverage remains as enchanting today as it was thousands of years ago. But instead of being trapped in history or myth, mead is alive, evolving, and buzzing with creativity.

Modern meaderies are proving that mead is far more than a relic of the past. With honeys that capture the terroir of their region, fruits that explode with flavor, and techniques that rival both winemakers and brewers, today’s makers are showing the world just how versatile this beverage can be. Sweet or dry, still or sparkling, traditional or experimental—there’s a mead for every palate.

Mead may be the world’s oldest fermented beverage, but its story is only just beginning—and the buzz is only getting louder.

Our Favorite Meads to Try Right Now

Photography courtesy of Gadi Solis (@gadi_solis)

Symbiosis – Coconut Dreamsicle – Standard Meadery

Villa Park, IL

Session Mead – If Lynch had to pick one Standard Meadery session mead to try, Symbiosis – Coconut Dreamsicle tops the list. The smoothie-style Dreamsicle mead with coconut has a 4.5 ranking Untappd, making it not one of but the all-time highest-rated session mead on the world’s largest social networking platform for craft beverage enthusiasts.

Florida Lychee – Zymarium Meadery

Orlando, FL

Session Mead – At Zymarium Meadery (one of our “Top Hidden Gem Places to Drink in 2024”), mead is magic. Leigh is a wizard at finding new flavors, experimenting with old ones, and combining complementary notes to make something you’ve never tasted before, bringing new regions of the world to life.

For instance, Florida Lychee, a session mead at 6.5% ABV, debuted on the opening day menu, but was originally just a mead Leigh made for himself.

“Whenever I eat lychees, I can never eat enough to be satisfied,” says Leigh, who made a mead that would drink like a really amazing glass of fresh lychee juice with orange blossom honey.

The mead turned out sweet, juicy, refreshing, and tropical.

One small experimental batch blew up.

Videos of the mead on TikTok had influencers crowding into Zymarium for the lychee mead.

Folks lined up for hours at festivals just to try it.

“People would walk in, and if we didn’t have the lychee mead, they just said see you later,” recounts Leigh, who quickly realized they needed to make this mead a flagship.

Currently, the lychee mead easily outsells every other one at Zymarium by two to one.

“It has become our gateway mead,” says Leigh, who emphasizes that Zymarium intentionally has a mead for everyone.

If you’re ever in Orlando, you might want to skip Disney World and head over to this magic mead kingdom instead. Just sayin’.

Scarlet Magick – Zymarium Meadery

Orlando, FL

Melomel Mead – Zymarium excels at letting the mead tell its story, whether that’s an expression of a specific honey varietal or a flavor melding of different fruits.

For example, Scarlet Magick, a hibiscus mead inspired by one of Leigh’s favorite drinks at a local taco spot, Hunger Street Tacos. After their hibiscus tea blew him away, Leigh had the idea to mimic the flavors through mead. The trick, Leigh learned after seeing them make the tea in the kitchen, was to use real hibiscus.

For the collab, Hunger Street Tacos dropped off fifty pounds of hibiscus. Planning to make a session mead, Leigh actually added the hibiscus during fermentation instead of finishing the mead on the flower. What Leigh expected to be a bright, fruity mead turned more red-wine tannic during fermentation. To balance, Leigh backsweetened the mead with panela sugar, also known as piloncillo, a traditional, unrefined sugar popular in Latin America. Even then, the mead still needed something. Leigh looked at spices traditionally used with hibiscus—ginger, cinnamon, and clove. He did a trial with clove first.

“It was one of those moments where you’re just like, I have never tasted this combination or anything like this before,” says the stunned meadmaker. “It was phenomenal; I’m now obsessed.”

Leigh calls the mead “magical.”

Released for Halloween, Scarlet Magick “quickly became people’s favorite,” gushes Ginger.

Photography courtesy of Superstition Meadery

Crystal Sail – Superstition Meadery

Prescott, AZ

Session Mead – “It’s awesome; it’s summertime,” says Herbert of the mango session mead. “I got goosebumps right now.”

Herbert says to drink this one chilled. Preferably on a hot beach somewhere, if you ask us.

Overall, he says, especially if you’re new to meads, you can’t go wrong with one of Superstition’s session ones.

Marion – Superstition Meadery

Prescott, AZ

Melomel Mead – If you’re looking for a gateway mead, Marion is the perfect introduction to Superstition.

The fruit mead made from blackberries, blueberries, raspberries, and Arizona wildflower honey has won a gold medal at the Mazer Cup, which is kind of like the World Beer Cup of meads, and is ranked as a top fifty mead in the world on Ratebeer.com.

Named after Maid Marion, the legendary love interest of Robin Hood, Marion just “checks those boxes of the style,” says Herbert of the meadery’s most popular bottle.

It’s a love letter to Superstition’s brand of semi-sweet 13% to 14% ABV meads.

“It’s the sweet spot where everything comes together,” says Herbert. “It’s perfect.”

Photography courtesy of Gadi Solis (@gadi_solis)

For Grace – Standard Meadery

Villa Park, IL

Melomel Mead – A mead Standard Meadery makes only once a year for its anniversary. For Grace falls into the more dessert-style category. The melomel includes black currants and Madagascar vanilla beans for a decadent treat that’s something to save for a celebration.

Miel de Garde – B. Nektar Meadery

Ferndale, MI

Traditional Mead – Another top-notch meadery, B. Nektar, brings mead to a whole new level. Nothing is off the experimental table at this Michigan-based fermentorium, whether it’s a mead with honey and cherries or one with black tea and lemon juice.

This traditional mead made with orange blossom honey gets a glow up by spending eighteen months in oak barrels.

With 470 rankings, Miel de Garde notches a 4.35 rating on Untappd, making it one of the highest-rated traditional meads of all time.

“Gloriously simple, but velvety smooth,” wrote one Untappd fan.

Black Agnes – Schramm’s Mead

Ferndale, MI

Melomel Mead – Founded by Ken Schramm, a prolific meadmaker who helped start the nation’s mead-specific competition Mazer Cup, Schramm’s Mead isn’t just one of the best meaderies in Michigan; it’s one of the top in the country.

Schramm literally wrote the book on mead, so his decades of expertise and experience translate brilliantly into his own spot (which, for the record, he resisted opening for many years).

It’s no surprise then that both Leigh and Lynch discovered a love of mead after drinking Black Agnes.

The black currant mead is “sharply tart and acidic,” according to the mead’s Untappd description, “the potent flavors of the fruit are perfectly balanced by the sweetness of premium honey to create a particularly unique, memorable, and delicious mead.

As both Leigh and Lynch will attest.

The former, an Untappd ticker and beer collector, used to have a spreadsheet with hundreds of super-rare beers. He and his friends would get together once a year to share everything they’d collected.

In one of those trades, someone gifted Leigh a mead as an extra. After trying all the beers, the group decided to open the fermented honey beverage, Schramm’s Black Agnes.

“We all took sips and just looked at each other,” recalled Leigh. “This was better than all the beers we just spent a lot of time and money getting.”

Leigh went whole hive collecting mead, spending not an insignificant sum tracking down bottles from meaderies all over the country.

For Lynch, after trying this mead for the first time, he thought, “Wow, I really liked this.” When he started his own meadery, Lynch felt Schramm’s approach to dessert-style meads with big flavor heavily inspired his vision.

If it’s great enough for Leigh and Lynch, it should definitely be good enough for you.

Sunflowers – Schramm’s Mead

Ferndale, MI

Traditional Mead – Schramm produces meads that focus heavily on local produce and ingredients. For instance, Sunflowers, whose curated blend of honeys creates a mead that’s “complex with alluring and beguiling aromatics,” according to the meadery.

With 447 ratings, Sunflowers hits a stratospheric 4.67 rating on Untappd.