Shop

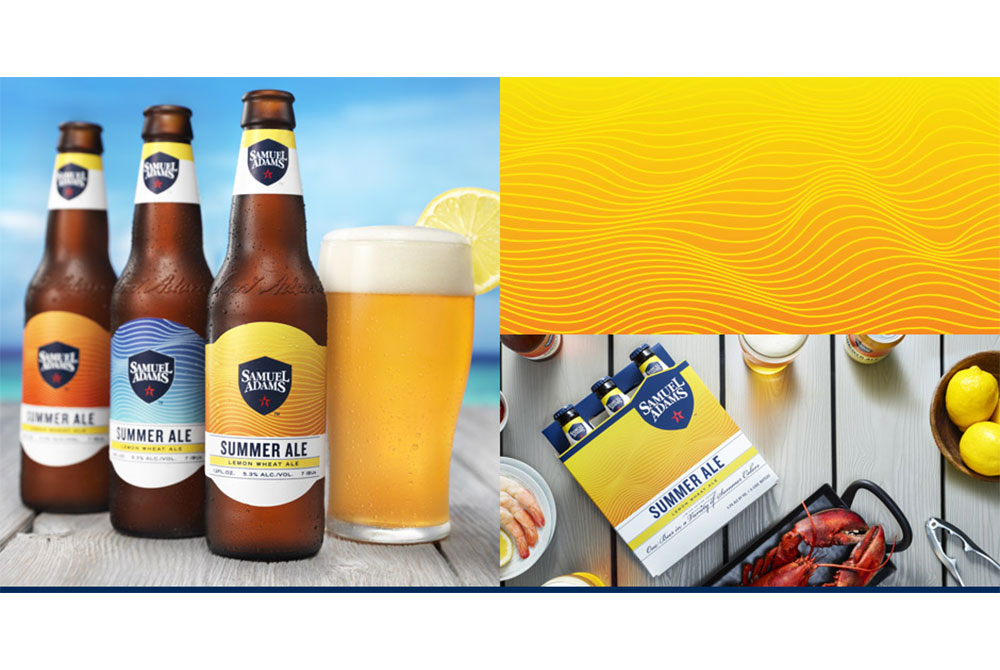

Local Beer Isn’t Just a Trend

How basic science shows that locally-sourced beer is here for good.

This article was originally published by our friends at BeerMenus, who — in addition to helping drinkers find craft beer — also run a blog.

Some folks think beer is like a can of soup: you can leave it on the shelf until you’re ready to drink it.

But the vast majority of beer is more like a loaf of bread — it tastes best fresh from the oven, and eventually gets stale and moldy. The popularity of local beer is rapidly growing because it’s got that “fresh-from-the-oven” taste. When a casual drinker has a supreme drinking experience trying a local beer, they’ll immediately taste the difference — and never go back to their old macro standby.

We’re not saying that you should immediately replace every brew on your tap list with a local one, but local beers are worth experimenting with because they have the opportunity to be fresher and better. Here’s the science behind why it’s worth it to serve local beers.

Don’t Truck Your Beer Across State Lines

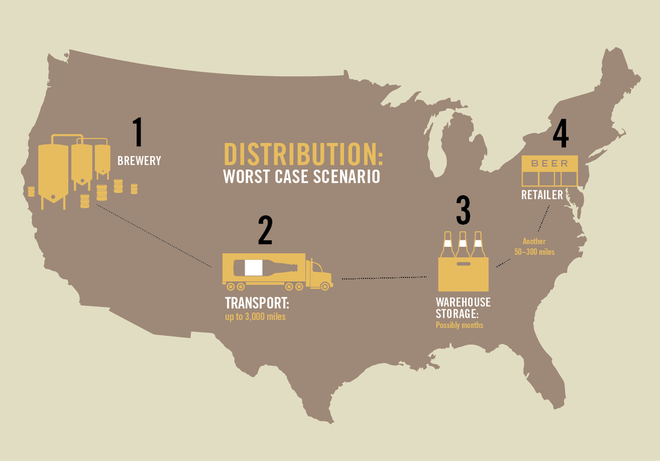

The worst-case scenario in beer distribution.

Since it can turn past its prime during the delivery process, distributors have to throw away a lot of beer. And that doesn’t even include the beer that’s about to go bad that’s making it onto your taps and shelves. The further a beer gets away from its home, the more time it has to deteriorate.

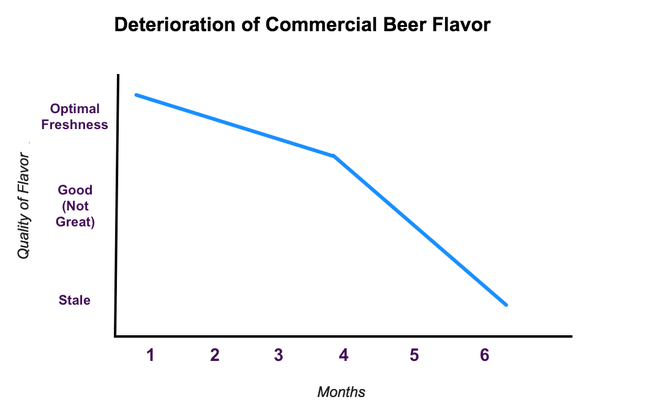

Beer taste deteriorates pretty quickly. Budweiser — which has the best age-fighting labs in the world — starts to deteriorate around the four-month mark. Four months might seem like a long time, but the graph to the left (or above on mobile) applies under perfect conditions: stored in the dark, and at a temperature of about 50-55 degrees Fahrenheit. But when you’re shipping beer across the country, there’s a lot of stuff that can happen to accelerate the process.

Because of post-Prohibition laws, a huge amount of beer must pass through a distributor before it reaches a retailer, which means it might have to travel 3,000 miles before it gets to a shelf. There are many factors on this journey that will negatively impact a beer.

- Shipping time length. Local beers have a lot less time between when they’re finished in the brewery and when they get to the retailer. According to HenHouse Brewing Company founder Collin McDonnell, just shipping a beer across the country can take a few weeks, whereas local brewers can often get their beers to local bars the same day they’re kegged.

- Storage time. Because it’s impossible to predict customer demand across the country, there’s often a surplus of beer that sits in a warehouse.

- Temperature changes. While storing beer at either too warm or too cold temperatures can affect its freshness, changing between different temperatures — exactly what happens when a beer changes hands — can also affect how long it stays fresh. Storing beer warm can bring the freshness window down to only 28 days for commercial beers.

- Light exposure. Exposing a beer bottle to light, even in a fluorescent-lit room, can do massive amounts of damage to the beer’s flavor.

- Confusing labeling. The “fresh by” dates on beer refer to optimal conditions, and there’s no way to guarantee those optimal conditions when the beer’s been shipped cross-country. While the packaging label can tell you when each beer was bottled, these can be intentionally unreadable to produce more profit.

Just a single factor going wrong on this list can put you in serious trouble.

A good drinking experience is a race against the clock, and local beer helps you in that race. As Troy Wennet, the beer buyer at Brooklyn’s 61 Local, says, “Fresh beer is the best beer. Some beer is brewed to age these days, but most beer is better the quicker it’s consumed post-fermentation and better the less it fluctuates in temperature.”

Eliminate the “Wet Cardboard” Flavor from Oxidation

There’s a chemical name for what happens as beer loses its flavor: oxidation. Long chemistry lesson short: oxygen creeps into your beer through the cap, then reacts with the hops and other chemicals, which changes the taste. Because the Earth is full of oxygen (bummer, right?), it happens to every beer eventually, without exception.

Here’s how people describe what beer tastes like in the first stages of oxidation:

- Wet cardboard.

- Wet paper.

- Lipstick.

When beer travels too long, it increases the risk that it will taste like wet paper. Beer stored at the wrong temperature speeds up the oxidation process immensely. CraftBeer.com cites the 3-30-300 Rule to show how much temperature matters: Beer stored in your car’s trunk at 90 degrees Fahrenheit for 3 days will taste the same as beer stored at room temp (72 degrees) for 30 days, or beer stored at 38 degrees for 300 days.

Changes in temperature speed up the oxidation process as well—which can happen as the beer changes hands. Beers that have been pasteurized and ones with lower alcohol content (two hallmarks of commercial beers) are also more sensitive to these changes.

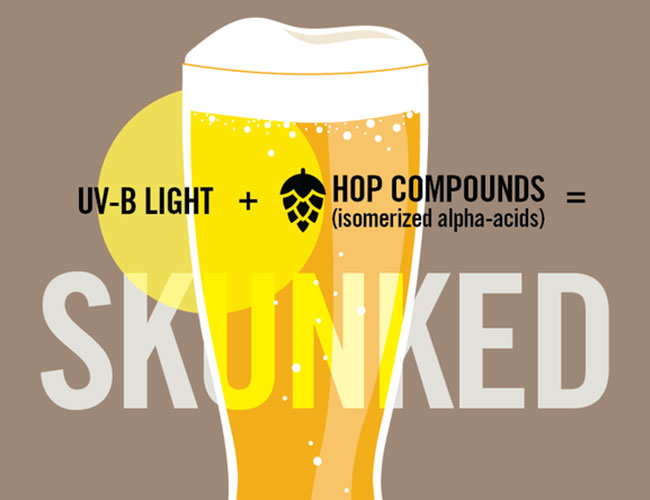

How Light Exposure Leads to “Skunking”

Acidic hop compounds transform into 3-methyl-2-butene-1-thiol, AKA “skunk spray.”

The phrase “skunked beer” is no joke. When exposed to light, the acid in beer actually produces the exact same chemical compounds as an actual skunk.

That skunk flavor is why it’s absolutely crucial to bottle beers in brown bottles, rather than green or clear. You might think it takes hours or days for a beer to skunk, but unprotected beer can start skunking in less than a minute if exposed to direct sun, in a few hours in cloudy daylight, or a few days in a fluorescent lit room.

Clear bottles give no protection from these effects, green bottles block 20 percent of light, and brown bottles block 98 percent. Contrary to popular belief, even beers dressed in brown aren’t totally immune to light exposure.

The usual suspects.

Local beers are less likely to skunk for a few reasons:

- Foreign imports use green and clear bottles more often, causing rampant skunking problems. In fact, [some European beer marketers](http://www.professorbeer.com/articles/skunked_beer.html) believe that Americans expect a skunked product, and even insist that breweries use skunk-prone glassware for their exports.

- More and more local beers are canning their beers because of this same reason. For reducing skunking, the only thing better than a brown bottle is a can, into which no light can reach. (And for those of you who still worry, it’s been official for years now: canned beer no longer means crap beer.)

- Because local beers don’t change hands as many times, there’s less of a chance it will get exposed to light in the distribution process—which is good for making sure that you’re not selling customers the stuff that literally comes from a skunk.

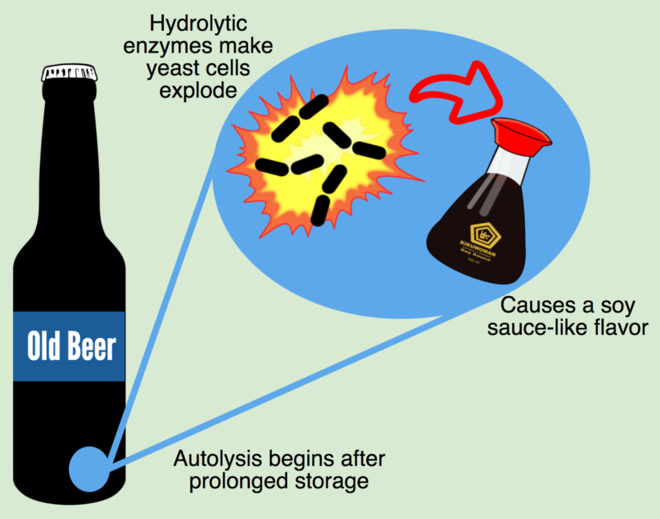

Beware “Soy Sauce” Flavor From Live Beers Gone Bad

When you bring in certain types of beer from far away, you run the risk of autolysis. As the yeast cells finish fermenting and die, their bodies break down and release an enzyme that tastes like soy sauce.

This only happens in bottle-conditioned beers, or “live” beers: beers that are carbonated using live yeast. The yeast at the bottom of each bottle ferment and produce carbonation over time, instead of pumping in all the carbonation in one fell swoop.

While “soy sauce” might not sound too bad, it’s definitely not what the brewer intended—or what the customer desired when they ordered it. They’ll be surprised (possibly disgusted) when that crisp Duvel they ordered tastes like meat.

Because of this, when you’re bringing in live beers, it’s a safer bet to bring them in from a local brewery.

When in Rome, Drink as the Romans Do

We’ll admit it: local beer doesn’t always taste better. Some of the 5,000+ breweries in the US simply haven’t yet found their groove, and that’s OK. Additionally, the patrons at your bar might have foreign favorites, and as a businessperson you should cater to their taste.

But local beer isn’t just a trend. It’s a realization about how good beer can be. So when you’re thinking about trying out some new beers, go local. Because of the race against the clock (and how it’s impossible to know how long it takes out-of-town beer to get to your bar), local beer always has the potential to be better than a brew from out of town.

But local beer isn’t just a trend. It’s a realization about how good beer can be.

Brooklyn’s 61 Local has a great recent example of making this switch. While they’re conscious of the locality of their entire beverage program, they had trouble sourcing what they like to call a “beer” beer (i.e. a light lager) from nearby breweries. As a result, they kept a pretty reliable easy drinking lager from Pennsylvania on tap, and it sold fine over time.

However, sourcing a more local beer nagged at the team, so they kept their eye out. When Folksbier Brewery opened up in neighboring Carroll Gardens, they had their answer: “I swapped out the PA beer for the Helles Simple Lager and we’ve received great positive response to its deliciousness and surprise that it’s made just down the street,” Wennet says. “We’re excited for the Helles Simple because it’s giving people who just want an affordable ‘beer’ beer awareness of what’s going on in the NYC beer scene.”

In addition to taste quality, serving locally immerses you in local commerce, local sustainability, and — most importantly — a local community. When people come to your bar, let them taste your local pride — and they’ll be coming back for more.