Shop

Meet the Artist Who Designed Our Favorite Beer Label of 2018

“Why can’t I taste beer online yet?

Few styles have dominated the craft beer industry quite like the New England IPA. The fervor around the style was carried by the perfect storm of social media influence, obnoxious collector mentality, streetwear-levels of hype, ardent supporters, and fierce critics. Luckily, in the midst of all this mayhem, some pretty solid beer was brewed.

As far as I can tell, no one has distilled the hype as succinctly as Jacob Ciocci has. Ciocci designed our favorite beer label of 2018: Cloudy Boyz, a collaboration between Marz Community Brewing in Chicago, IL and Collective Arts Brewing in Hamilton, ON. Both breweries are known for collaborating with talented artists on can designs and gallery installments (and they both make exceptional beer), so it’s no surprise they tapped Ciocci to make a beer label.

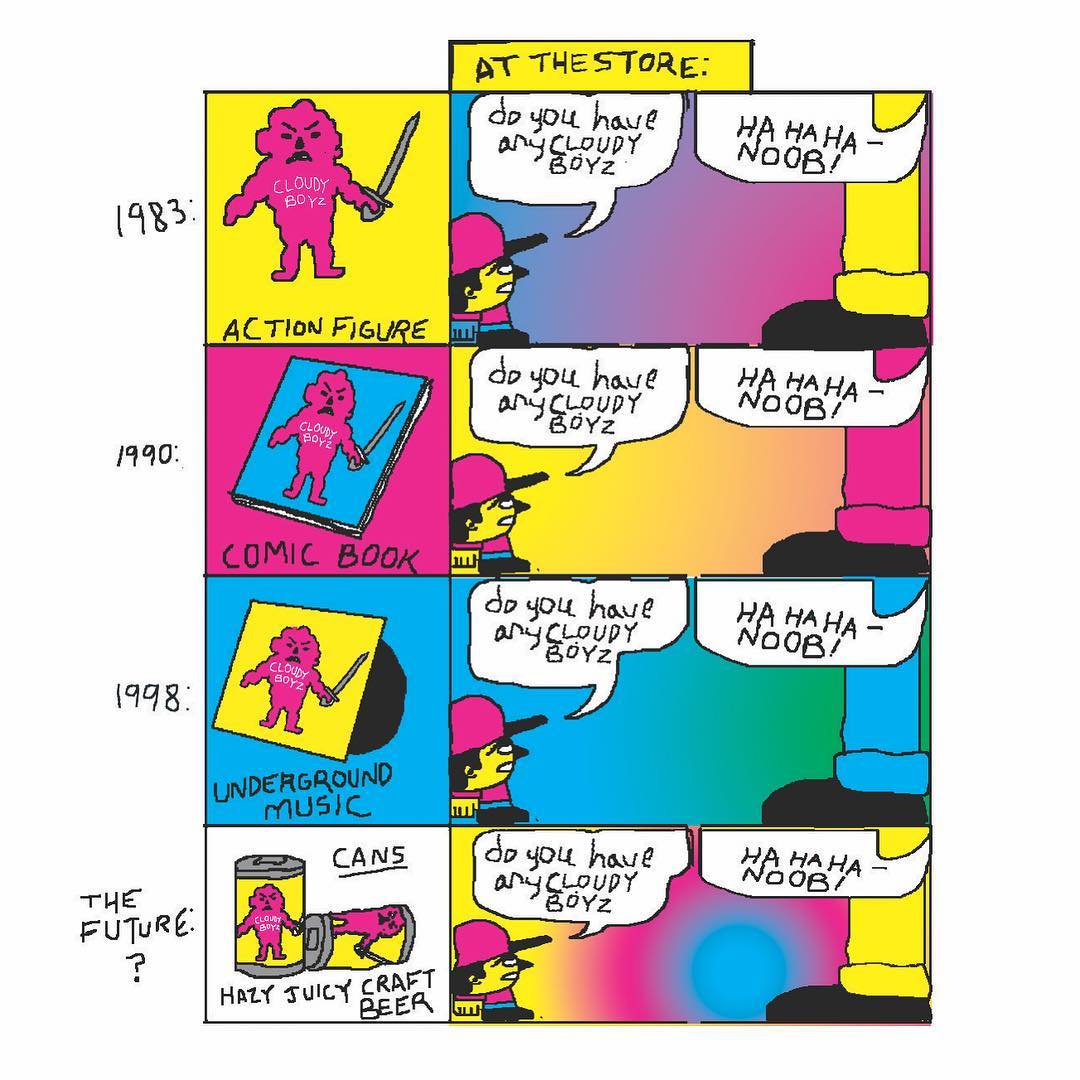

Though, as I found out in my conversation with Ciocci, he deserves a good chunk of credit for this beer. Not only did he say the phrase that would become the beer name (“Cloudy Boyz”), but he also designed the artwork without an ask from either Marz or Collective Arts. While Ciocci didn’t invent the convention of throwing “boyz” onto the end of a descriptor, nor is he the first to recognize the hype around hazy IPAs, he was able to place the craze around juicy brews in the context of record and comic book collecting in a way that both pokes fun at — and embraces — the hazy IPA moment.

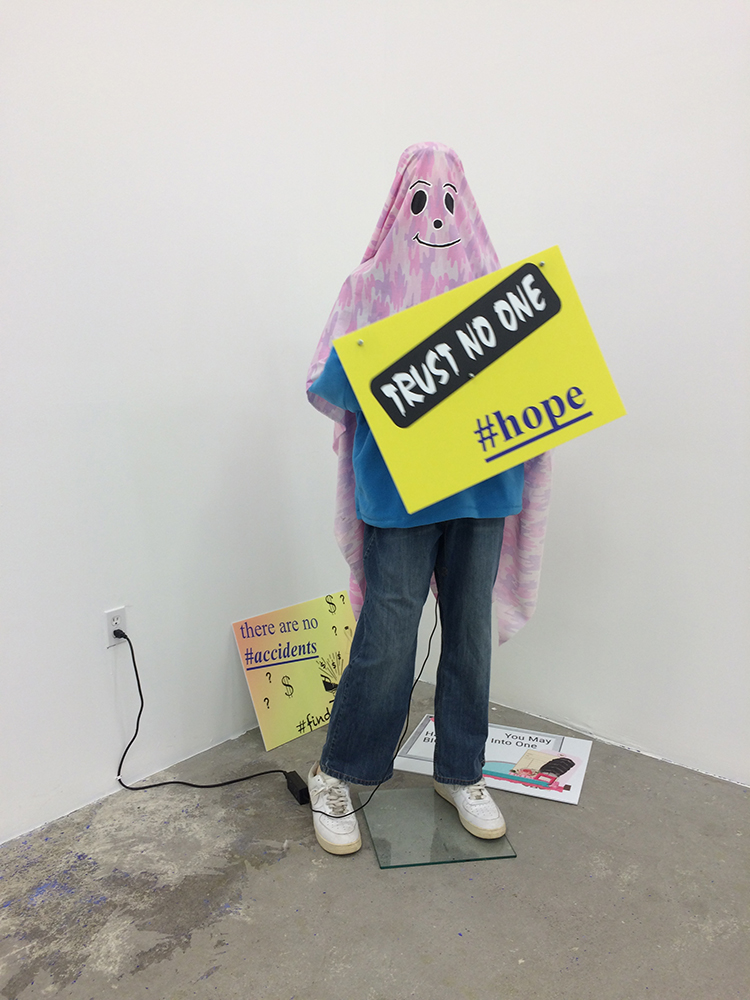

Photo courtesy of Jacob Ciocci

Before chatting with Ciocci, I had no idea how deeply he had thought about the craft beer industry; he could write one juicy research paper on consumer habits around New England IPAs alone. Jacob Ciocci is a surreal multi-media artist, the MFA Co-chair at DePaul University Animation Program, and a recent father. Check out his myriad thoughts on the beer industry below and catch Marz and Collective Arts at Juicy Brews Art Gallery in Chicago, IL on July 20.

John Paradiso: How did you get to know Marz and Collective Arts?

Jacob Ciocci: I met Edmar [Ed Marszewski, Marz founder] back in 2002 via DIY music, art, and comics. Living in Brooklyn, I slowly got into trying beer I had never heard of, but I had no clue about the hazy, juicy IPA craze until I moved to Chicago, about two years ago. I think when the great “Haze Craze” hit I was trying to learn how to enjoy cocktails.

When I got to Chicago I walked into a beer store and saw the Marz logo on an IPA. I could not believe how expensive it was for a 4-pack of 12-ounce beers. I also had no idea Ed was involved in making beer, but it didn’t surprise me at all. I had never heard of Collective Arts either but once I started asking the beer store guys about “hazers” they recommended that brewery to me.

JP: What was the design process like? Did Ed or Collective Arts give you any direction?

JC: I went to an art opening in the back of Marz Brewing and started talking to Ed. I asked Ed if he made any “cloudy boyz” because I didn’t know the real name for New England IPAs and he laughed. He said we should name a beer “Cloudy Boyz”. Then I went home and made the comic for the side of the beer, which explains my silly theory about beer collectors.

My theory is that the same impulse that drives the comic book collector in the ’80s or the record collector in the ’90s drives the beer collector today. The internet has changed comic and music collecting — because you can download free copies of the “content” of these mediums — but the internet has yet to significantly disrupt the experience of drinking a beer. Instagram and social media have only fueled people’s desire to buy beer, whereas Instagram and social media changes people’s desire to buy comics and records, as you can experience at least some version of that content online ahead of time.

JP: Were you familiar with the hype around hazy IPAs? Based on the art, it’s clear you understood the weirdness of the craft beer niche in some way.

JC: My take on the craze surrounding these beers is that it was a perfect storm: People were tired of all of the other beer styles, and this one felt new because it was about freshness rather than shelf-life or aging. Instagram enables you to find the freshest ones — only days after they have been canned. Your desire for any given beer only deepens if you fail to get there before the brewery or bottle shop adds the “sold out” edit to their Instagram post. You won’t make that same mistake next time.

If it were easy to get good quality craft beer at any corner store, and you were someone who liked the feeling of researching things you consume before you consume those things, then beer as a scene was getting stale. The New England IPA, aided by smartphone technology, made finding fresh haze into a game like Pokemon Go, something theorists call “Gamification.” I’m sure the hunt for beer has always been wild within the microbrew scene but I think the haze craze brought that hunting experience to a wider audience.

Photo courtesy of Marz Community Brewing

JP: When did you first encounter the craze?

JC: I had no idea what was going on at first. In 2014, I was living in Brooklyn and would see people post pictures of beers that were opaque and bright orange but I didn’t get it. I just thought these people had lost their minds. When I finally tasted my first hazy IPA — in Norway, of all places — a lightbulb went off in my head. A good NE IPA tastes the way I used to imagine the forest feeling when I would fantasize about living in a treehouse as a little boy. Fresh, thick, dense, layered, playful, free, peaceful, colorful. I always liked strong West Coast IPAs, but I remember thinking, “What if the tropical vibe was thicker?” Sour beers brewed with fruit started to taste too much like kombucha or vinegar to me.

By the time I figured all of this out, the NE IPA scene was already stale and the beer store guys were sick of explaining it to “newbz” like me. So it was a hilarious time to get psyched about something. That’s another parallel to records or music: By the time I got into Indie Rock in the ’90s I was so late, it was embarrassing. But I stuck with it anyway. I like to try and understand the hype as much as to try and understand the “content” of the hype. The culture around any content is sometimes more interesting than the content itself.

JP: Beer buying is becoming increasingly more visual. In a lot of cases, consumers purchase beer based on how cool the label art is. Do you have any thoughts on this?

JC:I think this trend has been going on with wine for many years. There is no way to know every wine brand. People pick a style they want and a price they can afford and then choose the one with the coolest label. Beer is now the same way, which I think is really fun. You can learn a lot about a society by comparing wine label designs and beer label designs. One could create a genius work of 21st-century cultural critique using only wine and beer labels. There is a lot of interesting gender politics embedded in wine and beer labels for example. There’s plenty to “unpack” in a 4-pack.

JP: Let’s get a little less philosophical. What does a typical day in the life of Jacob Ciocci look like?

JC: I am a new father. My son is 6 months old so my mornings are a storm of confusion and spit-up. My son brews his own milk-forward, low-alcohol session beer called “puke.” Each batch is slightly different. He is toying with various adjuncts such as pureed carrots and frozen blueberries but honestly, the smell and mouthfeel of his basic milk fermentation remains the best version to me.

When he’s sleeping, I might look at beer Instagram pages. When I’m teaching, I go teach and if one of the cool beers gets released that day, I call ahead to make sure the beer is still in stock, and then go to the store and get one four-pack. I predict within the year local beer stores will get so sick of people calling to ask “Has the haze dropped?” that they’ll just start hanging up on customers. It must get so annoying. I remember calling ahead to comic book stores in the ’80s and then record stores in the ’90s, desperately trying to get them to hold records or comics for me before I could get a ride to the store. The “no holds over the phone” policy of some of these comic and record stores is similar to the “limit one 4-pack per customer” occurring in modern-day craft beer bottle shops.

Photo courtesy of Marz Community Brewing

JP: Do you think you’d want to work on another beer label? Do you have any ideas you’d want to pursue?

JC: I definitely would love to do it, but only if I have another idea that feels important. I hadn’t read any other think pieces on NE IPAs quite like mine, so I felt like I had something to contribute. I’m not sure what else people are missing now. The scene changes fast, and I am no expert. I have however been thinking of a new concept. It used to be that a clever phrase could become a great band name. But bands have become boring, so, at this point, clever phrases are only useful for the following four things in culture: A beer name, a racing horse name, a name for a boat, an art show name.

I learned recently that racing horse names have rules and conventions one must follow. I suggest the same thing be created for beer names; there are way too many horrible beer names out there. I would rather drink a beer named with a series of numbers and characters, like a well-crafted password, than drink a beer with a horrible sounding name. I will not buy a delicious, highly sought after fresh $20 NE IPA if the name is offensive.

I’m sure I’m not the first to say this but every aspect of the experience of any given beer contributes to the “flavor.” Haze tastes better if you had to wait in a line to get it for example. Chefs in good restaurants have known this for many years. A good story about the thing you are experiencing can one hundred percent change the experience of that thing.

Liked this article? Sign up for our newsletter to get the best craft beer writing on the web delivered straight to your inbox.