Shop

Uncommon Common: What Is a Kentucky Common Dark Cream Ale?

Win, place, showstopper.

Like This, Read That:

Every country can lay claim to a few historic styles of beer. Germany has helles, kölsch, altbier, rauchbier, landbier, and Munich dunkel, to name a few. In Czechia, we find pilsner, Czech pale lager, Czech amber lager, and Czech dark lager. From Australia, we’ve written about the proliferation of XPA. In the UK, you’ll find ESB and Scotch ales. And Belgium has so many iconic styles from saison to lambic to kriek and everything in between. The one thing all these countries have in common? Those well-known styles are found pretty often and pretty ubiquitously (well, not Czech dark lager actually—that style is way more popular here). In America, though, some of our most storied styles are the hardest to find these days. We’re talking about steam beer (aka California Common), cream ale, and the Kentucky Common.

Ask yourself this question: Can you describe a Kentucky Common to someone else?

If you answered yes, you can probably stop reading. But if you found yourself fumbling for words, as we did, let’s set the record straight for you.

What makes this uncommon style worth exploring, who is still making it today, and where can you find some ridiculously good versions?

First, Just What the Heck Is a Kentucky Common?

Photography courtesy of Dallas DuBose | Untappd

Sometimes known as a dark cream ale, a Kentucky Common is a malty, brown-to-copper ale with a dry finish, higher carbonation, and lower ABV for high sessionability.

“I usually describe it to somebody as a lighter, dark brown ale,” says Blockhead Beerworks Owner and Brewer Rusty Schultz, who did a fair amount of research on the historical style before making his own. “It’s like a cream ale, but with roasted notes.”

A style native to America, the Kentucky Common is sort of a mashup of ingredients available in the mid-1800s and techniques brought over from European newcomers.

“They were trying to imitate German lagers with American ingredients,” explains Leah Dienes, head brewer and owner of Louisville-based Apocalypse Brew Works, which recreates a Kentucky Common from the early 1900s.

For instance, although not a hoppy beer by any means, Cluster hops were most likely used in a Kentucky Common because “we knew that’s what was grown the most,” says Dienes.

Likewise, corn is a staple in Kentucky Common mash because that’s what was available at the time.

“They had a lot of corn,” laughs Dienes, whose version of Kentucky Common is a replica from Oertel’s, Louisville’s largest brewery in the 1800s that used to be located just a few blocks from where Apocalypse Brew Works is today.

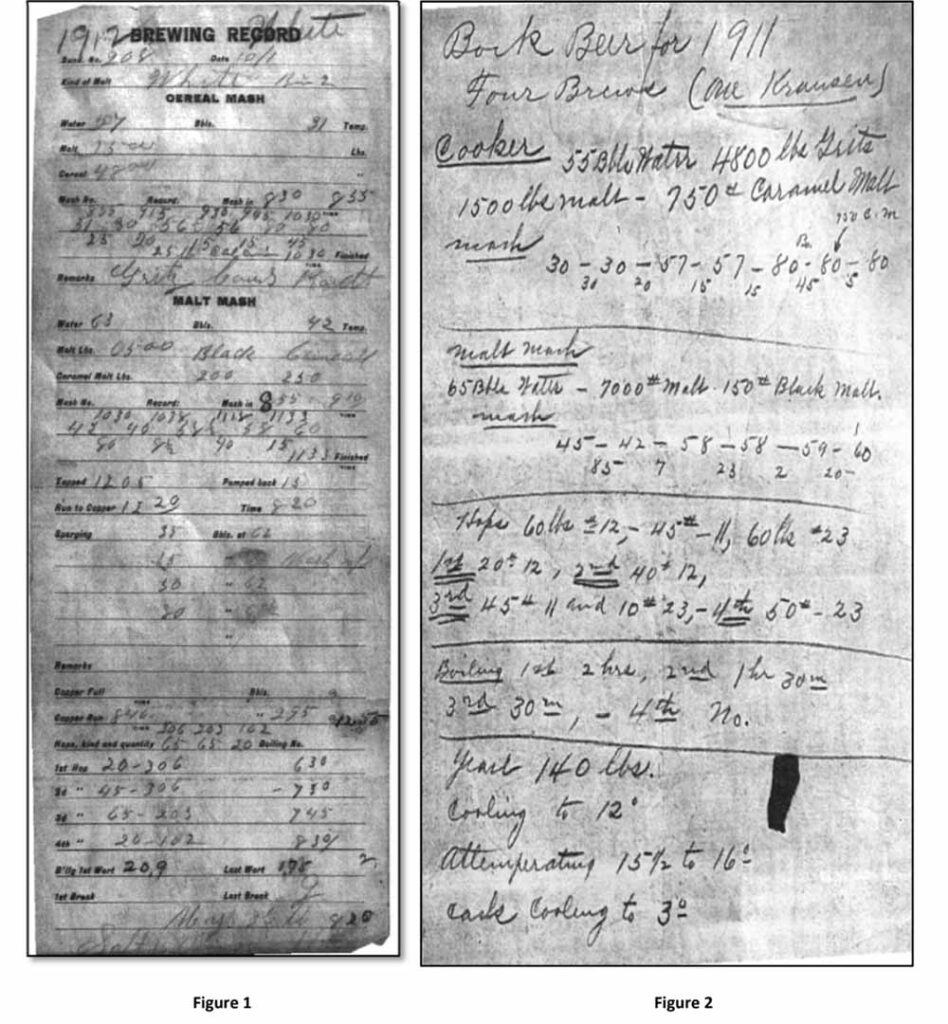

Dienes recovered Oertel’s original brewing log book from a friend in her local homebrew club who knew the widow of one of Oertel’s original brewers.

“We have the handwritten recipe,” she explains. “Because there were German brewers, everything was very precise. … It’s very detailed.”

Which is probably why, when you look up the definition of Kentucky Common from the Beer Judge Certification Program (BJCP), you’ll see Apocalypse Brew Works Oertel’s 1912 listed as the only commercial example.

Dienes has history on her side.

Putting the Kentucky in Kentucky Common

Example of an old Kentucy Common brewing record (on the left) and one of bock for comparison (on the right) | Graphic provided by Leah Dienes, Owner and Head Brewer, Apocalypse Brew Works

From the Civil War to Prohibition, Kentucky Common was produced almost exclusively in and around Louisville, Kentucky. Top-fermented Common ales were pretty, well, common in many regional areas like Chicago or Vermont, for example, but the Kentucky Common flourished for several reasons.

At the turn of the nineteenth century, close to one hundred breweries in the area produced this low-ABV dark ale because it was quick and inexpensive to make while suiting people’s tastes. “In the late 1800s, darker beers were still the norm,” says Dienes.

According to a paper by the president of Indiana Ordnance Works and Dienes titled Kentucky Common—An Almost Forgotten Style, “Around the turn of the century, Kentucky Common was delivered to the saloon cellar for five dollars a barrel; a raw product cost of two cents per pint to the saloon keeper. In comparison, Stock Ale was going for twelve dollars a barrel, and the newer and larger breweries producing lagers sold their product for eight dollars per barrel.”

Which probably explains why, at the start of Prohibition in 1919, at least seventy-five percent of all beer sold around Louisville was Kentucky Common.

Unfortunately, America’s thirteen-year ban on alcohol completely killed this regional style.

As Schultz points out, many of the breweries making the style before Prohibition didn’t survive. “Thirteen years is a long time,” he notes, adding that once Prohibition ended, no one was still standing to reintroduce it. And even if they were, “You’re talking about a whole [new] generation of drinkers. People’s tastes had changed.”

“Everybody switched over to lighter beers,” adds Dienes. “People didn’t want darker beers anymore.

Putting the Dark in Dark Cream Ale

Photography courtesy of Blockhead Beerworks

According to Dienes, a Kentucky Common grist historically includes up to sixty percent six-row pale malt, thirty-six to thirty-eight percent corn grits, and a tiny percentage of caramel and black malt.

Brewers likely used the latter to offset the nearby Ohio River’s historically hard water.

Dienes says the limestone in the area contributes to the water’s high levels of alkalinity and calcium. “We have really, really tasty water, which is handy, but I think that’s why brewers used those darker malts,” she explains, “to offset the hardness in the water.”

But the dark malts had additional benefits, including adding color and flavor to this dark cream ale.

For Blockhead’s cream ale, called Broker’s Tip, Schultz chose a Weyermann chocolate rye malt and caramel 40 “that added those roasted caramel notes to it,” explains Schultz, while the chocolate rye “has a spicier note and imparts really good flavor.”

How Do You Make a Kentucky Common?

To start, Dienes uses a cereal mash with the grits, which mainly gelatinizes the corn and converts those starches to sugar, and a quarter of the malt.

“We break down those starches and make them fermentable,” she explains, noting that a step mash follows with the rest of the pale and dark malts.

“After bringing that to a boil, you would add that back to the main mash to raise the temperature and then hold that. And then you would do your mash out, and then you just do your regular additions and everything else,” she says.

We know that corn was a main ingredient in a Kentucky Common, but not all breweries have the equipment to perform a cereal mash or step mash. Like at Blockhead, where Schultz bypasses that step on his tiny 5-bbl system by using flaked corn. Schultz says he includes roughly fifteen percent of that ingredient in his grist.

To hop a Kentucky Common, Dienes outlines the standard rates in her paper: Over a two-hour boil, you include a first addition, a ninety-minute second addition, a thirty-minute third addition, and a fourth addition at knockout.

Again, while the exact historical hops used are unknown, Dienes thinks Cluster hops from New York were the most likely source.

Figuring out the exact yeast was a little tricky, too, with Dienes admitting they first tried a lager yeast but realized it took too long to ferment.

Remember, Kentucky Commons at the time were prized for their cheap, quick turnaround. At Apocalypse Brew Works, they eventually settled on an ale yeast.

“We tried different ones,” Dienes says. “And then we just went off the taste because the description was crisp and clean with a bit of caramel flavor and dry finish.”

Dienes has documentation that fermentation lasted only three to four days at around sixty-six to sixty-eight degrees Fahrenheit. “The entire brewing cycle from cereal mash to finished beer ready for delivery was six to eight days,” she writes in Kentucky Common—An Almost Forgotten Style.

Wait, I’ve Heard This Is a Sour Beer?

It’s not. Or, at least, it’s not supposed to be.

There were sour versions, but Dienes doesn’t think these beers soured on purpose.

Instead, she guesses that when these mom-and-pop shops stored beer in barrels, they refilled old barrels that weren’t pitch lined, exposing them to lactic acid and “all kinds of fun bacteria living in the wood.”

She adds, “Because everybody made their own beer, they had it in the back, and it took them a while to sell it, so it probably could get sour in the barrel.”

Another clue: Breweries typically served Kentucky Commons in about seven to eight days, so without a sour mash, it would be impossible to get a sour beer.

Plus, bigger breweries, like Oertel’s, which made Kentucky Common every day, used pitch-lined barrels. And looking through their brew logs, which Apocalypse Brew Works has, it’s pretty clear: Their dark cream ale wasn’t sour.

What Does a Dark Cream Ale Taste Like? And Who’s Drinking It?

“[A Kentucky Common] is just supposed to be crisp, really clean, with a little bit lower hop presentation,” says Dienes, who often has to explain the style to folks before they’ll drink one.

“But once people try it,” she says, “they really enjoy it.”

Even though it’s a light beer, typically around 25 IBUs and 4.5% ABV, Kentucky Common has a lot of flavor and a nice crisp finish.

A Kentucky Common hits that nice middle ground for those looking for a darker beer without the perceived heaviness of a porter or stout.

Apocalypse Brew Works Oertel’s 1912 pours a dark copper with an off-white head. “Ours has a slightly caramel aroma,” explains Dienes. “And when you drink it, you’ll get a little bit of caramel and black malt. … Because it’s a dry finish, it doesn’t linger.”

Schultz says that you don’t need to overcomplicate things with a Kentucky Common.

“This is not a fancy [beer] by any means,” he says. “This is a classic nostalgic beer that’s all about the basics. When it all comes together, it’s a great-tasting beer.”

Still, this “great tasting beer” is a pretty esoteric style.

When I asked both Shultz and Dienes to name a few other breweries that make one, they could only come up with a couple.

“I think most of the people doing it are smaller breweries,” she posits, noting that despite being a local favorite, Oertel’s 1912 isn’t a massive seller for Apocalypse Brew Works.

Instead, Dienes calls her version “a great local beer that people want us to keep on tap all the time.”

“It makes you want to take another drink,” she adds. “You’re supposed to drink it, enjoy it, and have another.”

What Are a Few Versions of Kentucky Common I Can Try?

Oertel’s 1912 – Apocalypse Brew Works

Louisville, KY

The BJCP lists only one commercial example under its guidelines for Kentucky Common—Oertel’s 1912. Using detailed brewer’s log books from Oertel’s, Apocalypse Brew Works recreates this historical version as faithfully as possible.

“Nobody had tasted this beer in seventy-five years,” notes Dienes, who uses corn grits, a six-row pale malt, caramel malt, and black malt to give this beer its characteristic copper to light brown color and slightly caramelly aroma and flavor.

Lastly, “you’ll get that dry finish,” says Dienes. “It doesn’t linger.”

Which helps with this 4.7% ABV dark cream ale’s sessionability. “It makes you want to take another drink,” says Dienes.

If you’re looking for a great first version to try, this has to be it. Unfortunately, Dienes says their version is only available on draft in the taproom, so you’ll need to be in Louisville to try this one.

Broker’s Tip – Blockhead Beerworks

Indianapolis, IN

Schultz admits he hadn’t tried too many Kentucky Commons before attempting one at Blockhead. But with the Indianapolis-based brewery only a two-hour drive from Louisville, he became curious about this once ubiquitous dark cream ale.

Blockhead’s take on a Kentucky Common, Broker’s Tip is named after the winning horse from the 1933 Kentucky Derby.

Schultz thought it was a fitting name, considering President Franklin D. Roosevelt repealed Prohibition in 1933. He didn’t plan it this way, but fortuitously, Schultz released the beer during the actual race last year.

Now a seasonal beer in its second year, Broker’s Tip has become a bit of a fan favorite. “We had people asking throughout the year when we’d do it again,” says Schultz.

Blockhead’s recipe uses fifteen percent flaked corn, two-row barley, chocolate rye, and caramel 40 malt.

“Right away, I pick up the roasted flavor from the rye,” says Schultz. “It hits me from the first sip.”

The highly carbed beer pours a beautiful dark copper to amber and at 4.7% ABV is just an easier-drinking beer that our consumers seem to like,” says Schultz.

Kentucky Common – Falls City Beer

Louisville, KY

A suggestion from Dienes, the Kentucky Common from Falls City Beer includes corn, barley, and rye. Falls City Beer describes the grist as more similar to a bourbon distiller’s mash bill.

Adding rye gives this Kentucky Common a slight spiciness that pairs well with the sweet corn and malty barley.

Another local example, Falls City Kentucky Common does come in package, so you might have a slightly easier time finding this one.

One For the Books – Vine Street Brewing

Kansas City, KS

The historic Vine Street Brewing made One For the Books to celebrate the 150th birthday of the Kansas City Public Library. The third-highest rated Kentucky Common on Untappd gets a perhaps uncharacteristic vanilla addition for a slightly newer take on the classic American style.

This is the way to go if you’re a Kentucky Common connoisseur and want to try something a little different.

Old Growth – Tree House Brewing Company

Charlton, MA

The seventh-highest rated Kentucky Common of all time on Untappd, Tree House’s Old Growth includes a mash bill of six-row barley, corn, crystal malt, and black malt, paired with Cluster hops.

So, according to Dienes’ historic version, it is similar and accurate.

In the beer’s Untappd description, Tree House writes, “Pouring a deep orange color into the glass, it carries flavors of sweet corn, mildly caramelized malts, and earthy classic American hops.”

Knowing Tree House’s pedigree, we bet this would be a fantastic true-to-style version.