Shop

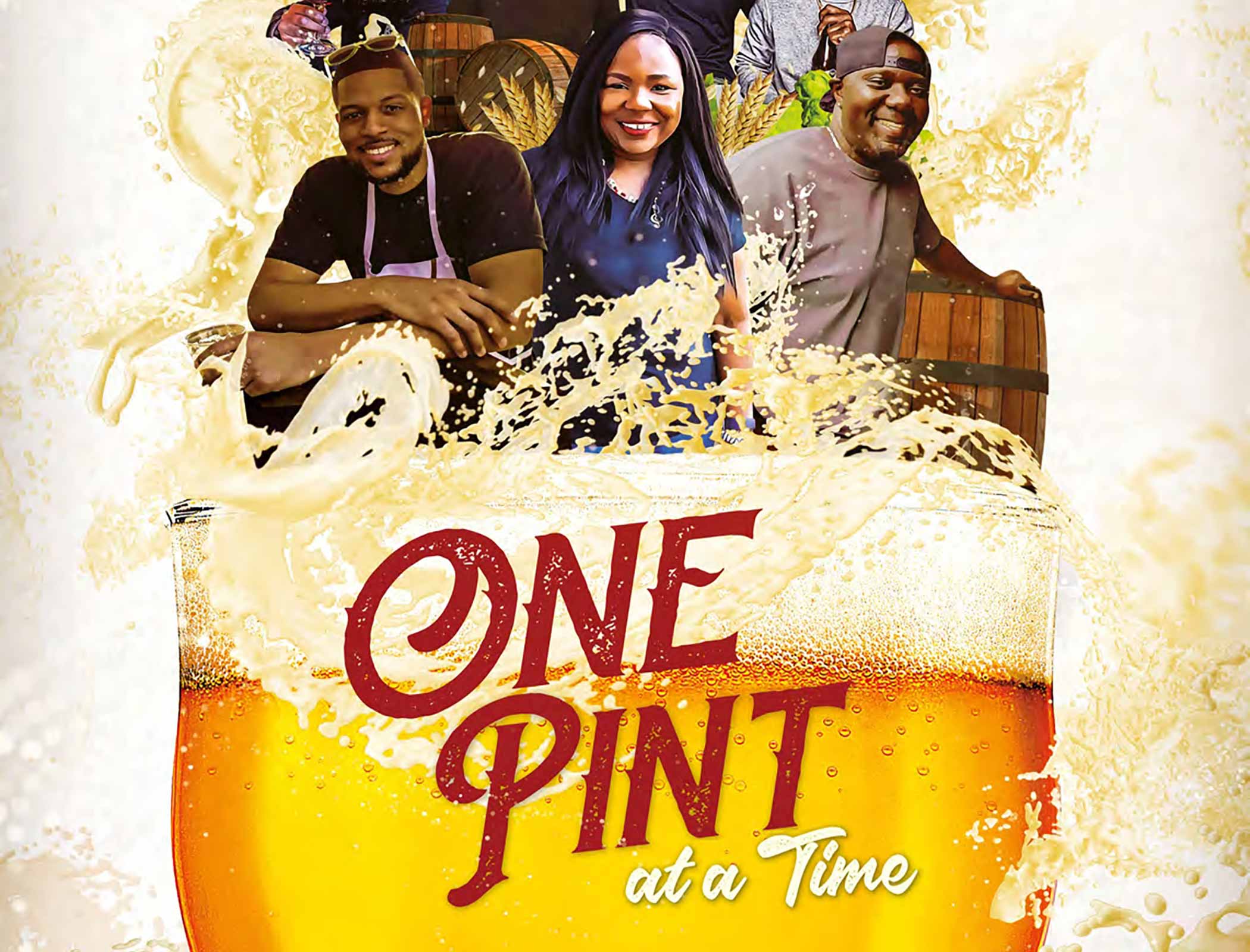

New Documentary Chronicles Black and Brown Brewery Owners ‘One Pint at a Time’

A first-of-its-kind film on Black and Brown brewery owners.

The sounds of a brewhouse—gears whirring, water boiling, steam hissing—are intersectional.

Words pop up on the screen:

“Each year, the craft beer industry generates tens of billions of dollars for the U.S. economy and provides hundreds of thousands of jobs.”

Hop pellets fall into a kettle, hoses swoosh and swish back and forth, and valves clink.

“There are approximately 9,000 craft breweries in operation in the United States today. Most breweries are white male-owned and have white male head brewers.”

A Black hand appears, corkscrewing doors closed, pushing buttons, dropping malt from a bag, twisting, turning, clamping…

“Only a fraction are owned by women and minorities or employ a female or minority head brewer. Multicultural consumers make up roughly one-third of the craft beer market. Yet, less than 1% of breweries are owned by African Americans.”

…and pushing play.

One Pint at a Time, a first-of-its-kind documentary from Aaron Hosé, five years in the making, delves into the Black experience in craft beer.

“All these other beautiful people we met weren’t having as easy of a time getting product out, getting brick and mortar green-lit and erected, getting locations, funding, and what have you,” says Hosé. “The struggle is real, the limitations of Black and Brown brewers are real … I wanted to highlight as much of it as we could … and celebrate as many successes as I could.”

Those like Huston Lett, co-founder of Bastet Brewing in Tampa, FL, spent five years trying to open the doors to his brick-and-mortar. Or Cajun Fire Brewing Co. CEO and Brewmaster Jon Renthrope, who is still trying to build a physical space for his brand. And Alisa Bowens-Mercado, aka Lady Lager, who started her own brewery Rhythm Brewing Co. in Connecticut, but currently contract brews her lagers at East Rock Brewing Company.

One Pint at a Time chronicles these journeys, zooming in on the struggles of the Black brewer in America through the lens of someone who has spent his life pursuing change through film.

From VHS Tapes to Taprooms

One Pint at a Time Filmmaker Aaron Hosé | Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

Hosé always loved movies. As a kid, the visual effects of Back to the Future and Star Wars moved him.

Growing up on the Caribbean Island of Aruba, a part of the Dutch Kingdom, Hosé dreamed of studying film, but he couldn’t get funding to leave the island and explore something like filmmaking, so off he went to Florida Tech in Melbourne, FL, for computer engineering.

“I realized very quickly … that wasn’t what I wanted to do,” says Hosé. “I always spent my free time watching films, going to the movies.”

Hosé says all the allowance his parents gave him, or the money he earned working in the school cafeteria, paid for movie tickets, cab fares to the theater, and VHS tapes. “I escaped life as a college engineering student to develop a deeper love for films,” he says.

Eventually, Hosé quit Florida Tech, moving to Orlando (considered the “Hollywood of the East” during the mid-to late 90s) to get an associate’s degree in film at Valencia College.

Two years later, he started freelancing on productions and making his films on the side, producing several short films and directing feature films about everything from disappearing Indigenous cultures to the LGBTQ+ experience through the eyes of twenty-year-old young gay, lesbian, pansexual, and transgender people in college to middle-aged Queer folx.

“I always wanted my films to help make some kind of difference,” says Hosé. “All [my] films had to do with a topic that felt close to me in a way.”

So when Hosé and his wife started avidly drinking craft beer, he saw an opportunity.

“We realized that we were the only People of Color or among the few in taprooms all over the country,” he says. “I got curious as to why.”

Hosé, who is part Black and Hispanic and speaks multiple languages, wanted to understand why he would go to drink a beer in a taproom with his wife, and if they spoke something other than English, people would look at them weirdly. “If that happens time and time again, you get a little uncomfortable,” he says. “That’s when you start looking around even more—that’s a white dude, that’s a white dude back over there by the tanks, more white dudes.”

Never before has someone pointed the lens at uncovering the lack of diversity in craft beer.

Until now.

One Pint at a Time Unpacks Years of Struggles for Black and Brown Brewery Owners

Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

Starting production in 2017, Hosé spent five years traveling, shooting, editing, and producing One Pint at a Time.

But the film reaches back even further, exploring the history of beer and how American craft beer came to be so homogenous.

Think about the pioneers—Ken Grossman, Jim Koch, Sam Calagione, Larry Bell, and Rob Tod, among many others.

All these white men represent some of the most iconic breweries in America. But that itself reflects a systemic dilemma.

“Craft has been impacted by the consequences of being a homogenous culture,” says former New Belgium Director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Courtney Simmons in our Creating Safer Spaces in Craft Beer series. “It’s not unusual for smaller organizations, start-ups, and entrepreneurs to rely on developing relationships in their known networks, which leads to this homogeneity.”

In other words, craft beer naturally evolved into a homogenous culture because many of those early pioneers all looked the same.

Craft x EDU Executive Director Dr. J. Jackson-Beckham explains in the film, “Those initial years in the ‘60s and ‘70s, what you had there was a time when people are taking a lot of risks. That risk, in particular, is what has become the center of these narratives around the people who blazed the trail back then. I call them our founding fathers.”

She continues, “Those stories provide the recognition those folks deserve, but they also perform a lot of cultural work,” says Jackson-Beckham. “One of the cultural effects of this narrative has been to gloss over the amount of resources that you needed to be able to take those risks. … One of the unfortunate consequences of craft beer is that there is an almost anyone-can-do-it-if-they-want-to idea that has been embedded in this narrative, and that’s simply not true.”

Jackson-Beckham explains that for someone from an underrepresented community, it would have taken an exceptional person with a lot of luck to find the means and access to capital to start a brewery.

Renthrope reminds us that a Black business couldn’t even own an LLC in the ‘60s.

For that reason, as craft beer exploded through the 1980s, 1990s, and early 2000s, the breweries opening up were by far and away owned by one specific demographic, attracting, in turn, a similar-looking cadre of drinkers.

“[One of} a few things that really came to the fore for me during filming … was the generational wealth gap and lack of access to capital that exists for minority communities,” says Hosé. “This inevitably makes it far more difficult to easily step into an entrepreneurial endeavor, such as opening a brick-and-mortar brewery.”

Even just finding a suitable location for a brewery can be challenging for Black and Brown brewery owners.

A struggle shared by three of the film’s protagonists—Lett, Renthrope, and Rhythm Brewing Founder Alisa Bowens-Mercado.

Bastet Brewing Brings Brewing Origins to Light

Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

Lett’s journey in craft beer starts perhaps like many of his white male counterparts. He fell in love with Bitburger Pils while working in the mailroom at a law firm and bartending some of the attorney’s parties as a side hustle. “It kind of blew my mind,” he says, eventually graduating to Rogue Dead Guy and beyond.

And after Lett’s then-girlfriend and now-wife bought him a Mr. Beer kit, he got hooked on brewing, especially after he nailed his first batch. “Everybody has horror stories about the first batch they made, but mine was actually pretty good,” he says, graduating from a kit to a small system on his stove to a one-barrel system in the garage.

But while his hobby took off quickly, getting an actual brewery off the ground started much more slowly and awkwardly. Especially because Lett rarely ran into people who looked like him.

“I equate it to the movies when somebody walks into a bar, the record stops, and everybody looks at the person walking in,” says Lett about the beginning. “There just weren’t a lot of people that looked like me.”

The disparity became even more apparent when Lett started working the festival circuit, sharing Bastet’s beers.

While setting up at events, Lett says, “People just stared at me like I had three heads.” And when they came over to try Bastet’s beers, they wouldn’t believe he actually brewed. “In the beginning, that really bothered me, but now, not so much,” he says. It’s a game now; how quickly can I surprise them with my knowledge.”

But Lett still questions, “Why am I getting asked tough questions when my peers right next to me that have less melanin in their skin aren’t getting asked those questions?”

Lett recalls one festival where five or six Black and Brown brewers poured. “We all knew each other, and we’re all giving each other dabs, like, ‘What’s up man?’” he recalls. “My wife seriously goes, ‘Do you know all the black people in the industry?’ And I’m like, ‘Yeah, I absolutely do because there’s only, like, five of us.’”

Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

Incorporating Bastet Brewing in 2014 with his business partner Tom Ross, who is white, Lett says it took five years to find an actual location. We’re dropped into the thick of his struggle in One Pint at a Time, watching Lett navigate the industry while searching for a property.

Lett’s story becomes a prominent feature of the film and, in some ways, a microcosm of the Black brewing experience.

Bastet gets its name from the Egyptian protector of Ra, symbolizing beer’s origins in Africa. “You’d be surprised at how many people think beer just fell out of Europe,” says Lett. Now, when people come to the taproom, which opened in 2019, Lett says they make a point of weaving in this narrative through art and beer. On many of the brewery’s Google reviews, Lett says you’ll often find comments like. “I came for good beer; I got good beer and a history lesson.”

At Bastet, you’ll find twenty-four beers on tap representing a variety of beer styles, backgrounds, and cultures.

“We take pride in variety,” says Lett, who also mentions their meticulous use of unique ingredients. At Bastet, you’ll find beers like ¡OLE! Tepache, a fermented pineapple beer originating from Mexico. Bastet’s version includes ginger and cardamom for a refreshing low-ABV fruit beer. Or Finnish Him!, a fermented Finnish lemonade called Sima with pulverized lemon—pits, seeds, skin, and all. And a sweet potato beer called ‘Tater Pie mimics everything Lett’s mom put in her own Southern Black family recipe. “It’s literally copious amounts of roasted sweet potato in the mash with cinnamon, nutmeg, and vanilla. And the result is just … fall in the glass for Southern culture—Black, Brown, whatever. That’s what you ate,” says Lett.

For Lett, the documentary became more than just sharing his story; it became a way for him to connect with other Black and Brown folks in the industry with shared experiences.

“I think [Aaron] did an amazing job,” says Lett. “It was good seeing my other peers, and it was interesting to see everybody’s journey … how pretty much everybody had a lot of hurdles, just like we did.”

Cajun Fire Brewing Co. Disrupts the Southern Market

Photography courtesy of Cajun Fire Brewing Co.

Similar to Lett, Cajun Fire Brewing Co. CEO and Brewmaster Jon Renthrope has spent years building his business and searching for a brick-and-mortar location.

A serial entrepreneur who started selling CDs in high school in the early 2000s, Renthrope discovered homebrewing in college at the University of Florida. Apprenticing at NOLA Brewing under former president and CEO Kirk Coco, Renthrope eventually set out on his own, entering competitions and showcasing at beer festivals.

Starting Cajun Fire in 2011, Renthrope says he “got too far from the lighthouse financially to swim back.”

But for the first Black-owned beer company in the U.S. South, Renthrope, who is also Native American, says finding a place in this space has been the biggest challenge.

Even though Black and Native Americans have always had a hand in brewing, very few people recognize these stories. While we all probably have some idea of how Sierra Nevada, Allagash, Boston Beer, or Dogfish Head started, for example, far less of us know about the story of Theodore Mack, who created the country’s first Black-owned brewery called People’s Brewing in 1972.

“The hardest challenge for me is finding these stories and preserving them,” says Renthrope, who has dug through archives in places like his family’s hometown in the bayou of Southern Louisiana

Renthrope, whose grandmother was the historian for the town, found records of different Black-owned moonshine facilities, inspiring him to start his own business that preserves Black and Indigenous culture in the state.

“If somebody looks like me, I could find out the barriers to entry into this space, how do these scale, and what are some of those shortcomings?” says Renthrope.

Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

For instance, the financial hurdle.

Despite raising over $900,000 for his community through Cajun Fire, Renthrope says not one bank has agreed to give him a loan for his brewery. He paid for everything out-of-pocket. “To be honest, I’m fatigued from that process,” shares Renthrope. I’ve just learned to be very unconventional when it comes to financial funding for my company.”

During COVID, Renthrope, who also serves as an executive director for a regional Black chamber, polled over 400 Black business members in the area, discovering that between eighty to ninety percent did not receive any COVID relief funds during the global pandemic.

“A lot of disparities still exist in those institutions,” he says, noting these are the types of straight-up systemic hurdles he experienced as a Black brewery owner. “Just being anything that ain’t heterosexual, white, or male anything of ownership, even like women of any creed [or] color, you got your cards stacked … you’re not really accepted at face value and … you got to jump through all kinds of hoops and hurdles.”

In One Pint at a Time, we watch Renthrope purchase land in East New Orleans off the I-10 Interstate, planning to open a cultural hub with a museum preserving local art and culture, a ghost kitchen available to underrepresented food business owners, and a Cajun Fire taproom as the anchor.

Several years later, Renthrope still hasn’t broken ground. In the meantime, people have vandalized the property, stolen fencing, and destroyed signs.

Renthrope says he even eventually stopped buying new signs because that cost him $600-$800 each time.

“I’m a market disruptor,” says Renthrope, who seemed to shrug all these incidents off as just par for the course.

Despite all the challenges, Renthrope remains optimistic, mentioning he’s still planning to build Cajun Fire’s cultural hub.

To him, the ultimate goal remains paramount. “Our mission is brewing for socioeconomic change one pint at a time,” he says. (And no, Renthrope isn’t sure if that’s where Hosé came up with the title for the documentary.)

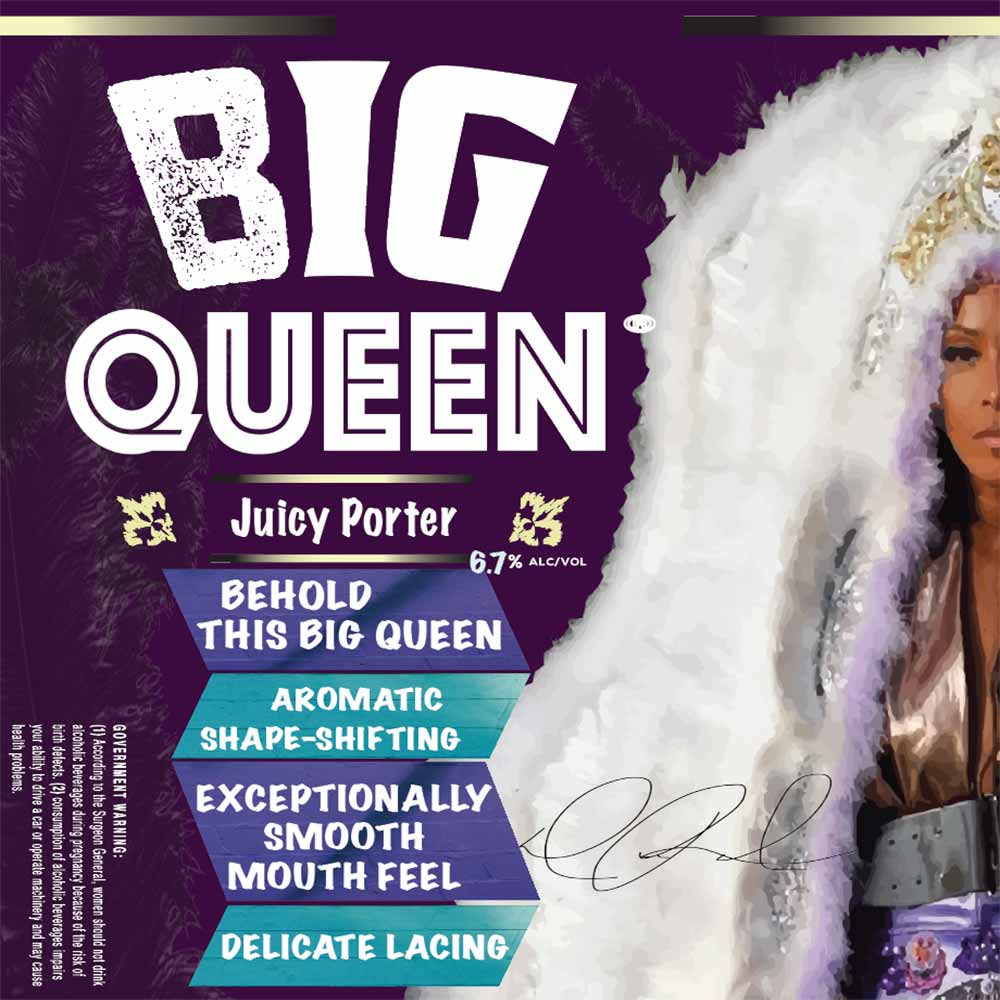

Each beer the family-owned and operated brewery makes represents New Orleans, paying homage to Renthrope’s Cajun Creole home and the United Houma Nation and African diaspora roots.

Like with their flagship Honey Ale, a Munich-style beer that nods to the fact that the area once had the country’s largest German population by density. Light and balanced, the honey ale has a profile that “just does something in this market,” says Renthrope. “Between the spicy foods and the humidity, people don’t necessarily want to drink a high-ABV [beer].”

Or P-Train Funk IPA, an IPA with raspberries that pays homage to New Orleans as the birthplace of Jazz.

A new seasonal beer called Big Queen Juicy Porter brings awareness to the local Mardi Gras Indian tribes.

“We try to be traditional, but we always add a unique twist with some Louisiana flair,” says Renthrope.

Although initially hesitant to participate in One Pint at a Time, Renthrope ultimately says he’s glad he could showcase New Orleans and some of his journey as a Black brewery owner.

“I’m glad I put some of my reservations down and opened up,” says Renthrope, especially because he had the opportunity to meet other Black brewery owners, such as Alisa Bowens-Mercado at Rhythm Brewing Co.

Rhythm Brewing Co. Steps to the Beat of Its Own Drum

Photography courtesy of (from left to right) Rhythm Brewing Co. and the National Black Brewers Association

Another prominent feature in One Pint at a Time, Bowens-Mercado started her brewery after she continually went to beer festivals and saw very few women, even fewer People of Color, and couldn’t find a beer that tasted like a classic lager.

In March of 2018, Rhythm Brewing Co. launched in New Haven, CT, as the first black-owned brewery in the state. Since the beginning, the brewery has been humming along to the beat of its own drum.

Opening a brewery for Bowens-Mercado (who also owns a dance studio) wasn’t just about the beer. Yes, she knew she wanted to brew a full-flavored craft lager, but more importantly, she wanted to get more women involved in the industry and open up doors for more brewers and consumers of color to feel included in the craft beer space.

“I tell people all the time we, as Black folx and People of Color, consume a lot of stuff, says Bowens-Mercado in the documentary. “[But] we don’t own these companies. … If we’re going to drink it, we should own it.”

Since launching Rhythm Brewing, Bowens-Mercado has sold beer in over 400 locations in Connecticut, earning the nickname Lady Lager.

Photo provided by Aaron Hosé

Her flagship beer, Rhythm Unfiltered Lager, uses South African hops to nod to Bowens-Mercado’s African heritage. Coming in at 5.5% ABV, Rhythm is also unfiltered, meaning all the flavor of the lager stays inside the can. “Our motto is we keep the goodness in,” says Bowens-Mercado in a piece for Hop Culture. “We don’t strip out the flavor.”

The brewery’s second brand, an unfiltered light lager, Rhythm Blue, clocks in at 4.8% ABV for a light, crisp, and refreshing beer. “We said let’s make a good ol’ fashion lager that’s light in calories but not light in flavor,” says Bowens-Mercado.

While brewing high-quality craft lagers has been the goal since day one, Lady Lager’s purpose with Rhythm reaches way beyond what’s simply in the can, disrupting the dynamics of the industry.

“I want to see a shift; I want to see a change,” she says in the documentary. “It’s not about me and that can of beer; it’s a bigger vision. This is a multibillion-dollar industry, and you look to the left and look to the right, and we get less than two percent of a billion-dollar industry. That’s not right. Not on my watch.”

To that end, Bowens-Mercado, along with Renthrope and Hosé, now sits on the Board of Directors of the newly formed National Black Brewer Association (NB2A), a collective organization promoting the Black brewing community, increasing African Americans in all levels of the industry, and fostering an understanding of the history of African American brewing in the U.S.

One Pint at a Time Inspires the National Black Brewers Association

Photography courtesy of National Black Brewers Association

Officially released in October 2021, One Pint at a Time screened at over 110 film festivals, picking up nominations or medals for 50 industry awards.

“We feel that’s nice, but those are all more vanity metrics,” says Hosé, “To me, the more humbling part has been the film’s role in the creation of the National Black Brewers Association.”

When Kevin Johnson, former NBA player, Mayor of Sacramento, CA, and founder of Oak Park Brew Co., saw the film, he’d already been wondering how he could help the Black craft beer community.

“Had the film not gotten to him, I can’t say the NB2A would not have happened, or maybe it would have taken longer,” says Hosé. One Pint at a Time featured many prominent members of the Black brewing community in one place for arguably the first time, connecting them.

Hosé says when Johnson watched the film, he had a moment of “Oh my god, there is a lot more than I thought happening in this community of brewers,” he recalls, mentioning that Johnson wanted to use his success and influence as a mayor, politician, and business owner to help establish the group. “Before I knew it … everyone was sitting together in a room in Nashville having their first board meeting; it’s crazy.”

For Hosé, that’s the most humbling part of the documentary “because I feel like this film has really made some kind of impact,” he says. “It’s helped create this organization that I’m confident will change a lot because every one of these heavy hitters in the Black brewing community is now under one roof.”

Renthrope says that before the NB2A, he had to find all the answers independently. “There weren’t any intentional organizations that assisted my needs as a Black brewer,” he says. Now he has folks to turn to who experience the same challenges. He can call Bowens-Mercado or Lett to chat or work on projects; he finally has a collective governing body to represent him.

“To start this journey five years ago and be here at CBC, the largest craft beer conference in the country … it really is surreal,” Bowens-Mercado told me at a bottle share for the NB2A in Nashville, TN. “Now I know that the work being done is not in vain. There is a lot of work to do, but collectively knowing that we’re all going in the right direction gives me even more drive.”

When We Know We’ve Truly Made a Difference

Images provided by Aaron Hosé

Lett says that since he started brewing, the industry has made leaps and bounds.

Hosé agrees that he’s seen things change for the better and remains hopeful that change will continue, especially since the stories he captured in One Pint at a Time keep unfolding.

While Bastet Brewing officially opened its taproom in 2019, Renthrope continues to move forward with plans for his East New Orleans cultural hub. In the meantime, he is expanding his distribution in the U.S. and, hopefully, abroad, he shared with me.

And Lady Lager continues to spread her beers and gospel across Connecticut and beyond.

Together with other Black and Brown brewers, these voices no longer quietly whisper alone but collectively shout to people who may not have heard them before.

“I’m just a guy who told stories that needed to be out there because they hadn’t been [told] before,” says Hosé.

Sharing stories is a start.

Creating the NB2A is another step forward.

But when will we know the industry has truly changed?

When I met Hosé at the Pink Boots Conference in 2019, I walked him through an exercise.

Imagine the last beer you drank. What did the beer taste like? Perhaps you had a hazy NEIPA and found notes of grapefruit and citrus. What did the beer smell like? Maybe you enjoyed an imperial stout and noticed coffee beans and chocolate aromas. Now picture the person that brewed that beer. What did they look like? Were they big and tall? Short and small? Blond-haired and blue-eyed? Most importantly, did you envision a man or a woman? Nine times out of ten, when asked to describe a brewer, people think of a big, burly man wearing a lumberjack flannel shirt and sporting a bushy beard.

Four years later, he reminded me of that conversation, saying, “When that shifts, then I think you’ll be like, ah, now we really … know changes permeated consciousness.”